Jephthah’s rash oath

Jephthah’s rash oath

Formations: July 24, 2016

Scripture: Judges 11:4-6, 29-40

Michael OlmstedBecause the Bible is about life, people and God, it includes tragedy and joy, failure and hope, and the powerful reminder that neither fate nor circumstance is the master of creation. Hence we have a story like Jephthah’s to remind us not to reshape God to fit our preferences or motivations. While Jephthah claimed a powerful military victory he failed to understand God’s character, left a legacy of tragedy, served only a few years as judge of Israel and is not celebrated for a legacy of peace.

Michael OlmstedBecause the Bible is about life, people and God, it includes tragedy and joy, failure and hope, and the powerful reminder that neither fate nor circumstance is the master of creation. Hence we have a story like Jephthah’s to remind us not to reshape God to fit our preferences or motivations. While Jephthah claimed a powerful military victory he failed to understand God’s character, left a legacy of tragedy, served only a few years as judge of Israel and is not celebrated for a legacy of peace.

Jephthah was a Gileadite and a mighty warrior. His mother was a prostitute, but his father treated him as a legitimate son. After his father’s death, Jephthah’s half-brothers resented his status as a legitimate heir and drove him away. He fled to the area of Tob, where a group of “worthless men” joined him and became proficient fighters (Judges 11:1-3).

Once again Israel lapsed into idolatry and God used the Philistines and Ammonites to oppress them. The elders of Gilead begged Jephthah to come to their defense, promising to make him not only their military commander but also their ruler (vv. 7-11). Consider the attraction of this offer to a man rejected by his own family and living in exile, now invited to accept the highest position in Israel.

Jephthah first attempted a negotiated peace, but when that failed he prepared for war (vv. 12-28). Headed for battle, the Lord’s spirit came to Jephthah (v. 29). In the time of the judges this event signals a victory. What more is needed than God’s promise of success? Yet, as Jephthah passed through Mizpah he made a vow to God: “If you (God) will decisively hand over the Ammonites to me, then whatever comes out the front door of my home to meet me when I return victorious from the Ammonites will be given over to the Lord. I will sacrifice it as an entirely burnt offering” (vv.30-31).

What was he thinking? Would he be greeted by an animal coming out of the doorway at his victorious homecoming? Was he uncertain about God’s faithfulness and believed his promised sacrifice would seal the deal? Or was he buying into the predominant religious thinking of that day that a sacrifice guaranteed a deal with one of the gods? In our time I have witnessed numerous promises people have made to God “if” he would solve a problem, heal or grant prosperity. Such promises usually came to nothing. Human sacrifice was forbidden in Israel, so this rash promise seems to come from a man who has suffered rejection by his own people and now feels God is no more trustworthy than them.

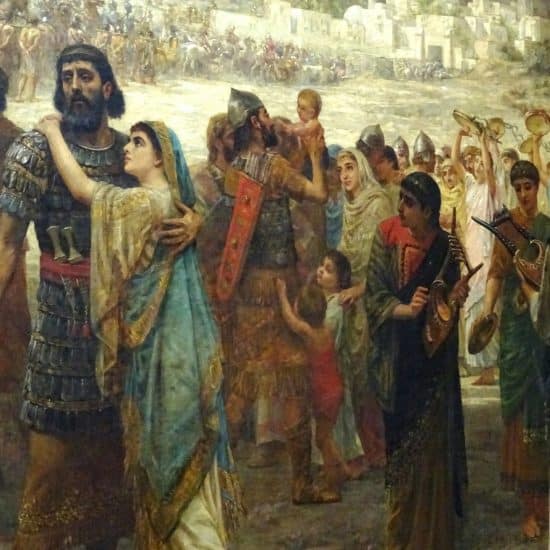

The text presents a strange connection between Jephthah’s vow and the victory. This is a story about God’s love and faithfulness to his people, even though they are repeating a cycle of sin and disloyalty to God. When Jephthah returned home in victory, the first person who came through the doorway of his house was his only child, his daughter, playing a tambourine and dancing. This was a common way to celebrate victory.

As further evidence of Jephthah’s foolishness and selfishness, he tore his clothes and cried out: “My daughter! You have brought me to my knees! You are my agony! For I opened my mouth to the Lord, and I can’t take it back” (v. 35). So it’s her fault she must die? In that culture she was not just a daughter, she was his only child, the one who could carry his name on to the next generation. Vows were sacred and any disavowal carried shame and even God’s punishment. But this vow contradicted forbidden human sacrifice in Israel. Faith is not based on bargaining with God, or promises for rewards, but about committing self to God, doing what is right, living out your commitment in a flawed world.

The daughter affirmed his vow to God (v. 36). She asked only one condition: that she be allowed to go to the hills with her friends to grieve and prepare for death (v. 37). The story ended not with a glorious celebration of Israel’s return to God, but with the tragic death of Jephthah’s daughter. Isn’t it curious that out of this story the women of Israel venerate this young woman as a hero, going to the hills every year for four days to celebrate her innocence and faith. She, not Jephthah, was the hero of this tragic story.

This story is one of many Old Testament narratives that reveal how human understanding of faith in God developed from Abraham’s first encounter with God to the day Jesus came to the cross. Judges is set in the context of a warrior people and a warrior God. Their understanding is limited and flawed.

Jesus spurns any idea of his people conquering the world by military force and placing him on a political throne. We read of Jephthah against a background of Jesus teaching us to forgive even our enemies, go the second mile, give to the poor and live by grace. As Jesus said, “You have heard it said, but I say to you!” (Matthew 24:21ff).

Jephthah’s problem is also our problem: Our ideas about God are too often shaped by culture and experiences. Some people dismiss the Old Testament as irrelevant in this modern world because it presents God as judgmental and harsh. I also hear statements about God that contradict the New Testament. We need to carefully consider our words before we judge who is a true believer, who really believes the Bible, who is a spiritually worthy political candidate and whose church is the true church.

We would also do well to measure our public vows to God, making sure they are both honest and true to the Bible. Jephthah’s words had terrible consequences. Our words can offer love, forgiveness and hope or they can promote division, hostility and violence. Religion has (and continues) to play a key role in genocide and war. Words are dangerously infectious when spoke outside God’s truth and grace.

This judge’s words, probably spoken out of emotional scars and a flawed picture of God, have left us a negative example. Only a handful of years passed between Jephthah’s victory over the Ammonites and Israel’s return to sin. May our choices, our vows and our living be less like Jephthah’s and more like those of our Savior.

Retired after 46 years in pastoral ministry, Michael K. Olmsted enjoys family, supply preaching and interim work, literature, history, the arts and antiques.

Formations is a curriculum series from Smyth & Helwys Publishing, Inc. through NextSunday Resources.

The PDF download requires the free Acrobat Reader program. It can be downloaded and installed athttps://get.adobe.com/reader.