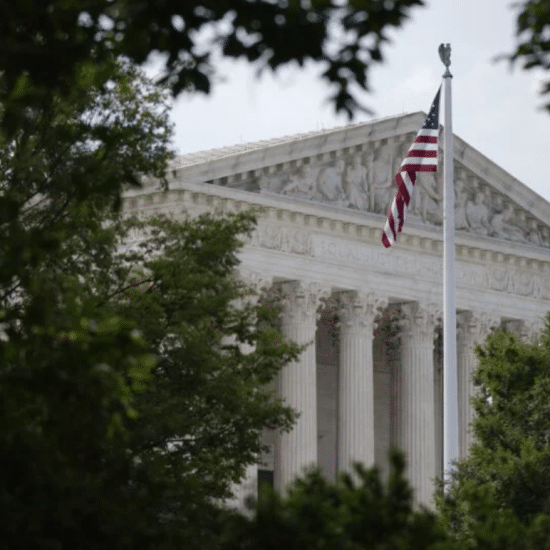

One of the most significant U.S. Supreme Court decisions in 2017 could come in a case from Columbia, Mo., concerning the relationship between church and state.

Trinity Lutheran Church applied in 2012 for a state program that reimburses non-profits for purchasing and installing recycled tire scraps to resurface playgrounds. Citing a state constitutional clause barring money to aid churches or religious sects, Missouri denied the church’s application for its preschool that operates in the church’s building.

The case of the Trinity Lutheran Church playground in Columbia, Mo., could factor into one of the most significant U.S. Supreme Court decisions in 2017. (Brian Kaylor/Word&Way)After the church sued, both the federal circuit court and the appeals court ruled for the state. The Supreme Court agreed last year to hear the case, now known as Trinity Lutheran Church of Columbia, Inc. v. Pauley.

The case of the Trinity Lutheran Church playground in Columbia, Mo., could factor into one of the most significant U.S. Supreme Court decisions in 2017. (Brian Kaylor/Word&Way)After the church sued, both the federal circuit court and the appeals court ruled for the state. The Supreme Court agreed last year to hear the case, now known as Trinity Lutheran Church of Columbia, Inc. v. Pauley.

The ruling could impact possibilities for state funding of religious houses of worship across the country as more than 30 states have provisions similar to Missouri’s.

Baptists engaged in religious liberty issues have split in assessments on the case. The Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty, an 80-year-old organization representing 15 Baptist bodies, filed an official brief with the Supreme Court urging the justices to uphold Missouri’s position. The BJC’s membership includes the American Baptist Churches USA, Churchnet, Cooperative Baptist Fellowship, National Baptist Convention USA and National Baptist Convention of America. The Southern Baptist Convention’s Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission instead filed a brief defending the church’s position. Liberty University, a Baptist school founded by Jerry Falwell in Virginia, and Union University, a Southern Baptist school in Tennessee, also joined a brief supporting the church. Michael Whitehead, legal counsel for the Missouri Baptist Convention, has served on the legal team representing the church.

Rudy Pulido, a retired Baptist pastor and vice president of the St. Louis Chapter of Americans United for Separation of Church and State, defends Missouri’s position as a reflection of “the tremendous contribution Baptists made” in promoting religious liberty and the separation of church and state.

“The separation of church and state is in the DNA of Baptists who have long realized that religion flourishes when it is voluntary, neither hindered or helped by government,” he explained. “Missouri’s Constitution is explicit in stating that no money shall ever be taken from the public treasury, directly or indirectly, in the aid of any church, sect or denomination, reflecting Jesus’s direction to render unto God what is God’s and to the state what is the state’s. Paying for a church’s activities, programs or facilities should not be done with tax money but rather by the voluntary donations of the members of the church.”

Political delays and changes

While the Supreme Court agreed in January of 2016 to consider the Trinity Lutheran case, the Court still had not set a date for oral arguments more than 11 months later.

Court watchers suggest this unusually long period between accepting a case and holding oral arguments could be the result of a vacancy on the Court created by the death of Justice Antonin Scalia in February.

Republicans in the U.S. Senate quickly declared they would not consider any nominee put forward by President Barack Obama. The Senate never held a hearing for Obama’s nominee Merrick Garland, whose nomination more than doubled the 100-year record for the longest nomination without a Senate decision.

“Being one member short for such an extended period of time has impacted the work and scheduling of the Court,” explained Holly Hollman, general counsel and associate executive director of the BJC.

Some Court watchers suggest the delay in Trinity Lutheran might be that the justices would prefer a full court so they could avoid the possibility of a split 4-4 decision on a critical church-state case. The justices have not explained the delay in scheduling oral arguments. They are still expected to hear oral arguments in time to issue a decision by late June.

While the Court vacancy likely delayed oral arguments, another political event occurred that could also impact the case. Missouri Attorney General Chris Koster, a Democrat, unsuccessfully ran for governor instead of seeking another term as the state’s top law enforcement officer and lawyer. As attorney general, Koster argued the state’s position at the lower court levels and filed briefs before the Supreme Court.

Republican Josh Hawley won election in November to become Missouri’s next attorney general on January 9, 2017. With oral arguments in Trinity Lutheran to occur after the transition, Hawley will take over the state’s handling of the case.

Hawley previously helped author a Supreme Court brief in the case. Representing the Assemblies of God, Hawley argued for the church’s position.

Pulido expressed concern that Hawley’s support of the church’s position means he may not represent the state’s interests. Pulido criticized Hawley for a record in church-state cases of seeking “special treatment from the government to allow the client’s religious beliefs to be forced on others.”

“[Hawley] has two options on this matter,” Pulido added. “He must either in good conscience recuse himself from the case or he must uphold his promise as attorney general to support the Missouri Constitution and thus change his position on the case and oppose Trinity Lutheran receiving any direct or indirect state aid.”

Hawley’s office declined interview requests.

See also: