(RNS) John Fuller recently made a monthlong effort to never utter a negative word to or about his wife, a busy mom he sometimes took for granted.

For a similar period, Katie Phillips found something positive to say about her 7-year-old son, with whom she had a “prickly relationship.”

Author Shaunti Feldhahn speaks at a Hearts at Home conference. Photo courtesy of Crown Publishing GroupAnd Christine King performed acts of kindness for an irritating co-worker.

Author Shaunti Feldhahn speaks at a Hearts at Home conference. Photo courtesy of Crown Publishing GroupAnd Christine King performed acts of kindness for an irritating co-worker.

Kindness — a virtue embraced by both the religious and the nonreligious — requires intentional behavior and can have beneficial results for both the giver and recipient of a benevolent act, experts say.

But, don’t we know that already? Aren’t most of us already kind?

We’d like to think so, said Phillips, an Atlanta-area mother of five, who took a “30-Day Kindness Challenge” earlier this year.

“But when you actually stop and think, ‘OK, what am I actively doing to please my child?’” said the woman who leads an adoption ministry at her church.

“‘How can I find little ways to make them happy, make their day, let them know I’m thinking about them?’” she added. “You’re really humbled because you think, ‘Oh my gosh, I don’t do this nearly as often as I thought I did.’”

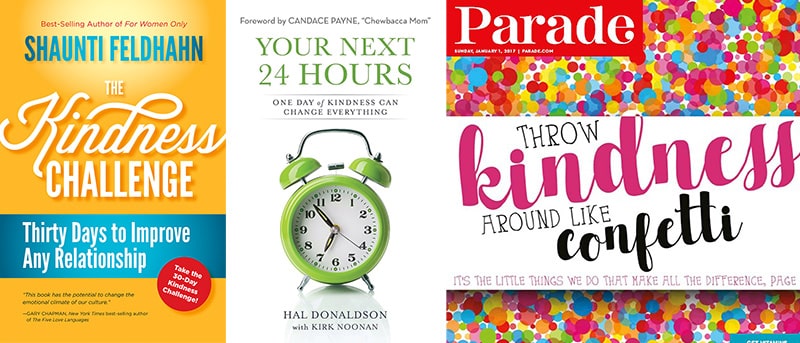

Some of the available resources to encourage kindness: “The Kindness Challenge” by Shaunti Feldhahn, “Your Next 24 Hours” by Hal Donaldson, and Parade magazine’s cover story on kindness.In recent months, Christian authors — as well as Parade magazine — have highlighted step-by-step processes to help readers learn how to be kind. Though organizations like the World Kindness Movement and the Random Acts of Kindness Foundation have encouraged altruism since the 1990s, more recent studies by scientists back up its benefits.

Some of the available resources to encourage kindness: “The Kindness Challenge” by Shaunti Feldhahn, “Your Next 24 Hours” by Hal Donaldson, and Parade magazine’s cover story on kindness.In recent months, Christian authors — as well as Parade magazine — have highlighted step-by-step processes to help readers learn how to be kind. Though organizations like the World Kindness Movement and the Random Acts of Kindness Foundation have encouraged altruism since the 1990s, more recent studies by scientists back up its benefits.

“People are longing for kindness,” said relationship researcher Shaunti Feldhahn, author of “The Kindness Challenge: Thirty Days to Improve Any Relationship.”

“Everybody likes living with a kind home, with a kind church, with a kind school and with kind neighbors.”

So she created daily goals for how to treat a friend, loved one or colleague: Say nothing negative, say something affirming and be generous to them in some small way. Feldhahn found that 89 percent of relationships improved when people took those steps for a month.

“They had trained themselves in purposeful kindness,” she said.

Convoy of Hope President Hal Donaldson has similar goals for a “revolution of kindness,” but for strangers as well as acquaintances.

“Hatred has just seized the headlines and anger is marching through the streets of our nation,” said Donaldson, author of “Your Next 24 Hours: One Day of Kindness Can Change Everything.”

“If we’re going to stem the tide of hatred and conflict, it’s not going to be through more hatred and conflict. It’s going to be through kindness.”

Donaldson knows about the benefits of kindness firsthand. His father was killed and his mother was seriously injured when they were hit by a drunken driver when he was 12. A family of four took in his family of six, sharing a single-wide trailer while their mother recovered. He and his brothers went on to found a Christian charity that mobilizes volunteers to help the poor.

But he has also worked on his own level of kindness — first for 24 hours and then trying to make it a way of life — from “being kind to a waiter to opening a door to jotting a note to a friend who I knew was going through a tough time.”

He made that plan after reading Proverbs 21:21: “Whoever goes hunting for what is right and kind finds life itself.”

Donaldson’s organization has distributed more than 20,000 copies of his book to churches, including The Chapel, a suburban evangelical megachurch in Chicago that focused on its lessons for three weekends starting on Easter Sunday.

Jamie Wamsley, associate senior pastor at The Chapel, sees the steps toward kindness as an antidote to the frightening headlines about the state of the world — laden with concerns about financial insecurity, race relations and military action.

“I think a lot of people are scared, and kindness, in the face of fear — kindness is a rare form of courage that really has the capacity, I think, to transform people’s perspectives and to profoundly help them,” he said.

A growing body of scientific evidence backs up the notion that kindness has benefits for a happier and perhaps even healthier life.

Professor Sonja Lyubomirsky. Photo courtesy of Josh Blanchard“People become happier over time when they are prompted to do more acts of kindness,” said Sonja Lyubomirsky, a psychology professor at the University of California, Riverside.

Professor Sonja Lyubomirsky. Photo courtesy of Josh Blanchard“People become happier over time when they are prompted to do more acts of kindness,” said Sonja Lyubomirsky, a psychology professor at the University of California, Riverside.

She and other researchers conducted a “Kindness in the blood” study involving finger-prick blood tests of three groups that did specific acts of kindness (for the world, for others or for themselves) and a neutral control group. They discovered that acts of kindness for other individuals prompted improved immune cell molecular profiles, involving stronger antiviral activity and less inflammation.

Other scientists have linked kindness to boosts in hormones such as oxytocin, which can lower blood pressure, and endorphins, which produce positive feelings.

But there also can be downsides to kindness, from being labeled a “pushover,” as Inc.com columnist Jessica Stillman wrote, to inadvertently aiding a disreputable cause.

“Don’t allow your generosity to be exploited and your good intentions to be thwarted,” writes Donaldson. “There are too many people who really need your help.”

And then there’s the century-old example from Jerome K. Jerome’s “The Cost of Kindness,” in which members of a fictional congregation despised their cleric, who had an “inborn instinct of antagonism to everybody and everything surrounding him,” but parishioners were so kind to him at his farewell ceremony that he canceled his plans to leave the church.

John Fuller of Focus on the Family. Photo courtesy of Sally DunnBut kindness, in real life, can be thought of as a personal goal.

John Fuller of Focus on the Family. Photo courtesy of Sally DunnBut kindness, in real life, can be thought of as a personal goal.

Fuller said his acts of benevolence — doing more household chores — for one loved one caused a “spillover,” where he now pays more attention to being kind to others in his life.

“It’s sort of like if I’m out of shape physically, I’ve got to start exercising,” said Fuller, who is a co-host on Focus on the Family’s “Daily Broadcast” show. “I became aware that I’ve got to be more proactive and more intentional with my good words.”

King, a former marketer who worked at the Hearts at Home ministry, said she learned the difference between being nice and being kind as she improved communications with her colleague by complimenting her more and complaining less.

“We all know that you should say ‘please’ and ‘thank you’ and hold the door,” she said. “Being kind is putting the other person before you and making an effort not to think the worst of them.”

Although kindness plans are often focused on individuals, group efforts have reaped rewards too.

Christ the Word Church in Rolesville, N.C., did its own “random acts of kindness” initiative last year by distributing more than $2,000 in gift cards to customers at local businesses.

“The people involved still speak of our experience of witnessing what a simple act of kindness can affect a person,” said the Rev. Patrick Cherry. “So often the seemingly ‘random’ act of kindness revealed people’s hidden pain, giving further weight to the old adage ‘You never know what someone is hiding behind a smile.’”

Feldhahn, who has taken her challenge to Christian conferences and secular corporations, said transformation in behavior comes as people turn their attention on themselves instead of trying to change others. She thinks the kindness steps could be applied in social media — and hopes grass-roots people might use them there to bridge divides with government public figures of opposing viewpoints.

“When you are kind to someone, you find yourself caring about them more,” she said. “You can disagree, but you stop being disagreeable about it because you care about them.”