2002. Fifteen years ago. A different time.

- President George W. Bush occupied the White House and Saddam Hussein still ruled Iraq.

- Barack Obama was a little-known state senator in Illinois.

- The first cellphone with a built-in camera was released.

- TV shows like “ER,” “Friends” and “The West Wing” dominated ratings, while “American Idol” started its first season.

- Johnny Cash released his final album before passing away.

- Salt Lake City hosted the Winter Olympics.

- The Anaheim Angels — now the Los Angeles Angels — won their only World Series.

- The Houston Texans started as an NFL team.

- The collegiate class of 2018 — about to start their senior year now — had just finished kindergarten.

August 13, 2017, marks the 15 anniversary of legal action taken by the Missouri Baptist Convention against five Baptist institutions.On Aug. 13, 2002, the Missouri Baptist Convention filed its first lawsuit against five Baptist institutions that shifted to self-perpetuating boards. Fifteen years and several million dollars later, 40 percent of the cases remain unresolved. Of the three cases completed, the MBC only won in the Missouri Baptist Foundation case. The MBC lost multiple suits against Windermere Baptist Conference Center, dropped their claims in a nearly-identical case against Word&Way and saw the estate of businessman William Jester win a settlement in a countersuit against the MBC.

August 13, 2017, marks the 15 anniversary of legal action taken by the Missouri Baptist Convention against five Baptist institutions.On Aug. 13, 2002, the Missouri Baptist Convention filed its first lawsuit against five Baptist institutions that shifted to self-perpetuating boards. Fifteen years and several million dollars later, 40 percent of the cases remain unresolved. Of the three cases completed, the MBC only won in the Missouri Baptist Foundation case. The MBC lost multiple suits against Windermere Baptist Conference Center, dropped their claims in a nearly-identical case against Word&Way and saw the estate of businessman William Jester win a settlement in a countersuit against the MBC.

Fifteen years and multiple judges later, two cases — Missouri Baptist University and The Baptist Home — have yet to even go to trial. The next hearing in those cases — previously scheduled for June 21 — is now set for Sept. 18, though it could be delayed again.

Fifteen years ago, the MBC found itself at its financial peak. At the 2001 annual meeting, messengers approved the largest MBC budget ever — $20 million — for 2002. The 2017 budget is just over $14.8 million, back down to levels from the late 1980s (though inflation makes today’s giving worth less than in the 1980s). While the MBC’s budget has dropped 26 percent in 15 years, the Southern Baptist Convention’s Cooperative Program budget during the same time rose more than seven percent. The MBC employed over 70 staff in 2002, but now employs less than 50.

The threat of lawsuits at the 2001 annual meeting led to a split in Missouri Baptist life as another state convention formed in 2002. Since 2002, the MBC has lost two executive directors amid scandals and severed its historic ties with another institution (William Jewell College). The number of churches and missions affiliated with the MBC dropped from 1,959 in 2002 to 1,809 in 2016. Total membership in the churches and missions dropped from 605,986 in 2002 to 452,840 in 2016, while total baptisms dropped from 13,646 in 2002 to 7,712 in 2016. Meanwhile, the lawsuits continue, outliving several Baptist leaders on both sides of the conflict.

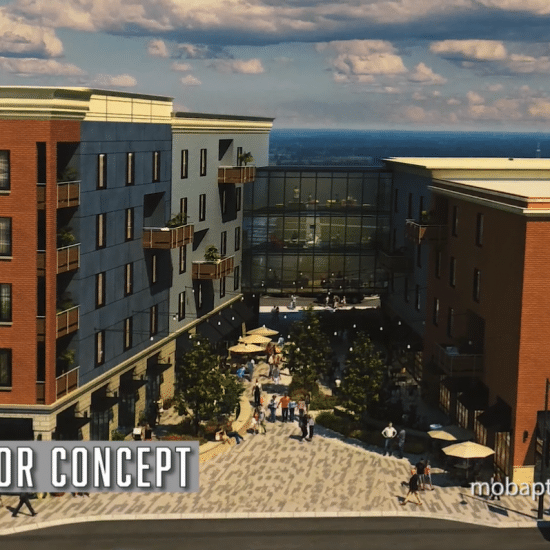

During that same time, MBU experienced strong growth — even upgrading from a college to a university in 2002. Its total student population in various programs in 2002 was just over 3,200 students; in 2017, that number is a record 5,700, making it now the largest Baptist college in Missouri. Gaining approval for its first graduate program in 2000, MBU now offers 11 graduate programs. In 2008, MBU launched its first online degree program and now offers 12 online programs with hundreds of classes.

TBH has similarly seen growth, including its upcoming fourth residential site in Ashland, Mo. In 2006, TBH started a focus on global aging, partnering with Baptists in other nations to help them with caring for seniors through residential homes, retirement planning and educational programs. Through these partnerships, TBH has worked in nine countries, with more than half of the partnerships developed in the past four years.

Other institutions sued by the MBC — like Windermere Baptist Conference Center and Word&Way — have struggled more, in part due to the litigation and what leaders of those organizations called tortious interference by MBC leaders. The later efforts included efforts to stop contractual relations between the institutions and other organizations. WBCC documented many of these efforts in a public statement in 2006, noting that the MBC’s “efforts to harm Windermere” included successfully urging leaders at other ministries — including Focus on the Family and LifeWay Christian Resources — to cancel events at WBCC. The statement also noted MBC leaders contacted bank and construction companies to try and stop those businesses from working with WBCC.

The contacts to banks and construction companies — as well as false statements published by MBC leaders — formed much of the basis for Jester’s countersuit against the MBC. After Jester’s death in 2010, his estate received a $500,000 settlement from the MBC in the case in 2012, though MBC leaders did not inform Missouri Baptists about that settlement until months later after EthicsDaily.com broke the story (written by the current Word&Way editor).

WBCC filed a suit against the MBC in 2013 based on claims similar to those made by Jester, though WBCC later voluntarily withdrew the suit. Word&Way trustees in 2006 similarly threatened a lawsuit against the MBC based on tortious interference after MBC leaders contacted Baptist organizations to urge them to stop advertising in Word&Way. The trustees decided against suing, but maintained that the MBC’s actions were wrong.

As the five institutions changed to self-perpetuating boards in 2000 and 2001, the questions of ownership quickly arose. Although the institutions were independently-incorporated nonprofits and were not listed as assets in MBC audits, MBC leaders claimed the MBC owned the institutions and thus the institutions could not make the boards self-perpetuating.

Prior to 2000, however, the MBC claimed on several occasions that it did not actually own the institutions. In 1978, messengers at the MBC’s annual meeting voted to accept a report from a special committee formed to study the “ownership of institutions.” The report noted that institutions that “are separately incorporated” — like the institutions that later moved to self-perpetuating boards — are not owned by the MBC. The MBC did own things like its building, some student centers and — at that time — WBCC (though the MBC later changed that status in 2000). The report also noted that for the MBC to own the institutions, the MBC would have to be incorporated and “all assets of the individual institutions would have to be transferred to the incorporated Convention or trustees for the Convention.” Additionally, the move would require eliminating the institutions’ charters “since the institutions would cease to exist as a separate legal entity, but would only exist as a part of the Convention.”

The 1978 report — the most recent on the subject — went on to recommend against the MBC seeking to own the institutions. Reasons given included legal fees, increased liabilities, potential loss of some properties deeded to institutions, accreditation concerns for the colleges and less effectiveness for the institutions since the MBC’s trustees would govern each institution instead of more specialized trustees on the separate boards. Additionally, the report argued the move toward ownership and greater centralization did not match historic Baptist doctrines.

“Baptists have historically favored the priesthood of the believer and local autonomy,” the report noted. “Central ownership would be a movement away from our historical principle and a move toward authoritarian control and structure.”

A 1998 MBC video on “trustee relationships and responsibilities,” which was used for orientation of trustees of Missouri Baptist institutions, also explained the MBC did not own the institutions. The half-hour video outlined several MBC reports — 1877, 1927, 1931, 1945 and 1978 — that each concluded “the agencies were autonomous bodies” and therefore “separate, legal entities under the laws of the state of Missouri.”

“It’s a popular misconception that these institutions or agencies are owned by the Convention,” the video added in explanation to some of the trustees who would later vote for self-perpetuating boards. “The fact is, they are not owned in a legal sense by the Convention — and it’s important that you understand the legal position of the Convention and the legal position of the institutions.”

The MBC’s claim of non-ownership even appeared in a court case. In October 1982, a Southwest Baptist University student, Alan Wright, was seriously injured during an SBU hayride. Left a quadriplegic, Wright filed a $10 million lawsuit in March 1983 against SBU, the professor driving the tractor and the MBC’s executive board. (The MBC as an unincorporated entity cannot sue or be sued, but the executive board is an incorporated entity tasked with the business of the MBC outside the annual meeting). Then-MBC Executive Director Rheubin South responded to the lawsuit by saying the MBC is “certainly sorry about the accident,” but he insisted “the Missouri Baptist Convention executive board does not own or operate Southwest Baptist University or any college.”

Earlier this year, a court filing by MBU referred to the MBC’s “judicial admissions” in that 1983 case as the MBC “confirmed” the “voluntary relationship” between the MBC and the institutions.

“The MBC advised the trial court that the MBC ‘had no power or authority to veto, prohibit or limit in any way any decision or other action by the Board of Trustees of Southwest Baptist University,’” MBU’s filing notes. “The MBC also admitted that if Southwest Baptist University did not seek approval before making a charter change, ‘the only act which the Convention could take would be to not make a contribution for the next fiscal year.’”

The SBU lawsuit was settled the next year for $3.5 million, with $3.415 million from SBU, $10,000 from the professor and $75,000 from the MBC’s executive board. MBC leaders agreed to the settlement with the stipulation they did not admit to any liability. South expressed concerns that ascending liability cases “may rise to haunt all our institutions in the future.” That issue of ascending liability later played a key role in the move toward self-perpetuating boards.

Ascending liability means someone could sue the MBC in addition to one of the institutions — as occurred in the 1983 SBU case. Descending liability means someone could sue the institutions when also suing the MBC in an attempt to tap a larger pool of money for a legal judgment or settlement.

“The more control that it appears that the executive board exerts over the particular institution, the more possibility that there will be what’s called ‘ascending liability’ from the institution up to the executive board,” the MBC’s 1998 trustee training video explained. “So, this relationship is one that we want to be careful with because the more ties that we find between the two, the more possibility there is of the ascending liability being a significant problem. That’s something that’s obviously not desirable; we don’t want that to happen.”

Following the 20-0 vote by TBH trustees on Sept. 12, 2000, TBH leaders explained the move would protect Missouri Baptists from ascending liability litigation, particularly noting the rise in litigation against nursing homes. Attorney Dwight Cole, who advised the trustees before the vote, explained at the time that the election change “is the only legal way currently available” to prevent liability claims that could threaten the MBC or TBH. Then-TBH President Larry Johnson said shortly after the vote that the action “removed a legal bridge that invites litigation.”

Other institutions received similar legal advice from attorneys steeped in corporate law. When WBCC trustees voted to go self-perpetuating on July 30, 2001, and when MBF trustees voted to become self-perpetuating on Oct. 10, 2001, trustees for both institutions explained they acted as part of their fiduciary responsibility and over concerns about liability lawsuits. On Aug. 23, 2001, MBU trustees also became a self-perpetuating board. President Alton Lacey noted, “The only way to limit this ascending or descending liability is to make these changes in the trustee selection process.” MBU trustees also expressed concerns about interference in the trustee selection process due to the MBC’s use of unapproved rules in 2001 to disqualify some trustees, an issue that Word&Way trustees also noted as they voted on Oct. 19, 2001, to move to a self-perpetuating board to protect the ability of the publication to freely report news.

Recent litigation involving other Baptist state conventions demonstrates the potential of liability claims. Already in 2017, individuals have sued two state conventions due to alleged child sex abuse at an affiliated institution. An alleged rape last summer at Falls Creek Baptist Conference Center in Davis, Okla., sparked a lawsuit in March against two Baptist churches and the Baptist General Convention of Oklahoma, which owns and operates Falls Creek (similar to WBCC’s relationship with the MBC prior to 2000). The suit, which seeks $75,000 in damages from each party, claims the organizations failed to ensure a background check that would have discovered an existing criminal record for the alleged rapist, who was arrested and charged shortly after the incident.

In April, the Southern Baptists of Texas Convention found itself sued over alleged neglect and physical and/or sexual abuse of seven children in foster care at the Texas Baptist Home for Children. The SBTC supports the TBHC as one of its “affiliated ministries,” which means the SBTC provides Cooperative Program funds to the TBHC and has trustee board representation (but does not choose a majority of TBHC’s trustees). Although this relationship is weaker than what the MBC previously had with the five institutions that shifted to self-perpetuating boards, it has still led to the lawsuit against SBTC. The suit seeks $1 million for each child for the abuse allegedly caused in 2013 by four foster-parent couples living in cottages on TBHC’s home campus.

The issue of ascending liability for the MBC remains untested since the 2000 and 2001 actions as none of the institutions that did not change have faced serious litigation that entangled the MBC.

See also:

Looking Back on Legal Promises

Legal Timeline Follows Controversy Legal Timeline Follows Controversy