In 2001, the first draft of the human genome was published in the journal Nature. The research effort sought to identify all the genes in human DNA and to determine the possible sequences of the chemical bases that make up human DNA. Francis Collins, a physician, geneticist and Christian who now serves as the director of the National Institutes of Health, led the project, which he described as “a narrative of the journey of our species through time.”

The completion of the Human Genome Project raised a significant question in Christian circles: Who are Adam and Eve in light of the conclusions?

“The results of the Genome project suggest that a set of ten thousand people started the human race, which challenges the literal interpretation of Adam and Eve in Genesis,” said Bing Bayer, professor of Old Testament and Hebrew at Southwest Baptist University in Bolivar, Mo.

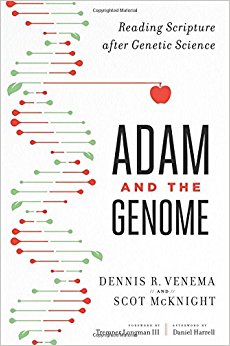

In their recently published book, “Adam and the Genome: Reading Scripture after Genetic Science,” evangelical geneticist Dennis Venema and New Testament scholar Scot McKnight explore questions pertaining to evolution, genomic science and the historical Adam, arguing that genome research and Scripture are not irreconcilable. Scientific research, as well as research in the arts and humanities, regularly casts new light on ancient life and culture. As a result, biblical scholars and lay people alike must grapple with the implications of the research on their understanding of the Bible, particularly the Old Testament.

In their recently published book, “Adam and the Genome: Reading Scripture after Genetic Science,” evangelical geneticist Dennis Venema and New Testament scholar Scot McKnight explore questions pertaining to evolution, genomic science and the historical Adam, arguing that genome research and Scripture are not irreconcilable. Scientific research, as well as research in the arts and humanities, regularly casts new light on ancient life and culture. As a result, biblical scholars and lay people alike must grapple with the implications of the research on their understanding of the Bible, particularly the Old Testament.

“When we read the biblical text, we must realize it’s really a Middle Eastern document,” says Steven Ortiz, professor of archaeology and biblical backgrounds at Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary in Fort Worth, Texas. “The Bible was written in the soil of ancient Palestine. God revealed himself to a particular people. Critics and fundamentalists alike come to the biblical text and want a word-for-word analysis, but history doesn’t work that way. I think there’s a lot of confirmation, but there’s seldom direct one-to-one correspondence.”

As Venema and McKnight make clear, Old Testament inquiry often requires asking questions. The answers may require a willingness to accept different possibilities.

Take for instance the story of the Golden Calf fashioned by the people of Israel while Moses was on the mountain receiving the Ten Commandments. In her 2014 article “Metallurgy in the Bible,” published in Jewish Bible Quarterly, chemist Susan Meschel,adjunct professor at the Illinois Institute of Technology, argues that the method of fashioning the calf is less interesting scientifically than what the Bible says about the destruction of the calf.

Passages in both Exodus and Deuteronomy say Moses burned the calf, ground it to powder, threw the dust in the brook and made the Israelites drink it (Ex. 32:20, Deut. 9:21). Problem number one from a scientific view is the reference to “burning” the gold as opposed to the normal process of melting metal. A second question is how the burned metal could be ground into dust. A third issue is gold powder would have quickly sunk in the water before he Israelites could drink it.

Certainly, a miraculous work in the burning and drinking of the dust is possible, a literal reader might argue. However, David Frankel, senior lecturer in Bible at the Schechter Institute of Jewish Studies, suggests a wording rearrangement might be in order. Frankel “hypothesizes that an ancient editorial or copyist’s error occurred and suggests reversing the two parts of Ex 32:19-20 as follows: ‘He became enraged and hurled the tablets from his hands and shattered them at the foot of the mountain; then he ground it to powder and strewed it upon the water and so made the Israelites drink it,’ followed by ‘He took the calf that they had made and burned it.’”

“In this reading of the text, it is not the gold that is pulverized and scattered over the water but the tablets,” Meschel writes. “Assuming that the tablets were of limestone or marble, the process is technically quite reasonable. Limestone can be broken and powdered without the use of any sophisticated equipment. Such powder would mix with the water and could float on it, since its density is not high.”

Meschel’s exploration of metalworking in the Old Testament also suggests that craftsman skilled in metal working would have been valuable members of ancient societies like the Israelites of the Old Testament. She notes that early books of the Bible deal with manufacturing objects from silver, gold and copper, which are metals with relatively low melting points. In contrast, iron would have been harder to work with because it has a higher melting point. Therefore, to fashion implements from iron would require hotter furnaces and possibly the use of forced air to increase the temperature.

1 Samuel 13:19 states that “no smith was to be found in all the land of Israel, for the Philistines were afraid that the Hebrews would make swords or spears. So all the Israelites had to go down to the Philistines to have their plowshares, their mattocks, axes and colters sharpened.” As a result, on the day of the battle, “no sword or spear was to be found in the possession of any of the troops with Saul and Jonathan; only Saul and Jonathan had them.” Later kings, including Uzziah of Judah, provided shields, spears, helmets and coats of mail (2 Chronicles 26:14), but Scripture does not say who provided them.

The value of ironsmiths is also evident in 2 Kings, which notes that Nebuchadnezzar “deported thousands of skilled workers: He exiled all of Jerusalem, all the commanders and all the warriors — ten thousand exiles — as well as all the smiths and artisans” (2 Kings 24:14). Eventually, Isaiah tells us there were skilled Hebrew ironsmiths (Isa. 41:7 and 44:12), which meant the Israelites no longer had to outsource their tools and weapons — a useful development to be sure.

Perhaps the biggest question regarding the Old Testament among evangelicals today is how the Old Testament relates to Christ, says Stephen J. Andrews, professor of Hebrew and Old Testament at Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary in Kansas City, Mo. Some Old Testament scholars have begun referring to the Old Testament as the “Hebrew Bible,” sometimes used as justification to ignore how the Old Testament speaks about Christ, he said.

At the other extreme, is the “Christocentric” approach, which involves looking for Christ in every passage of the Old Testament and opens the door to “fanciful interpretations on every page,” Andrews said.

A better way, he suggests, is not to hold the Old Testament at arm’s length but rather to follow Paul’s advice that all of the Old Testament — law, history, poetry and wisdom and prophets — are to be examples to us.

“We confess this is the Bible, so the question is: How can the church find the Christian Scripture here? How does the Old Testament tell us about God’s will, God’s nature, God’s purpose? How do we go back and find Christ, the Messiah, and how do we approach the Old Testament with the power of the Holy Spirit?” Andrews asks. “It does matter.”