(RNS) — A group of Christian college students has released a survey that suggests censorship of student publications is not uncommon at American Christian schools, with student editors alleging faculty and administrators wield broad editorial control over campus newspapers and sometimes kill  A recent study suggests widespread censorship of student publications at American Christian schools. Photo illustration by Kit Doylestories before publication.

A recent study suggests widespread censorship of student publications at American Christian schools. Photo illustration by Kit Doylestories before publication.

Administrators at Christian colleges have a legal right to control their schools’ newspapers, and argue they do so to safeguard the values that define their institutions.

“There are certain sensitivities that you’re just going to have to respect about campus culture,” said Greg Bandy, faculty adviser to the newspaper at Asbury University in Kentucky.

Many student journalists at Taylor University, northeast of Indianapolis, insist the restrictions imposed on them at their newspaper, The Echo, go too far. They wanted to know if their peers at Asbury and other Christian schools share their frustrations — and the results indicate they do.

The study, conducted this spring, was not sponsored by Taylor, a nondenominational Christian school, but by the Student Press Coalition, which was created by the Taylor students.

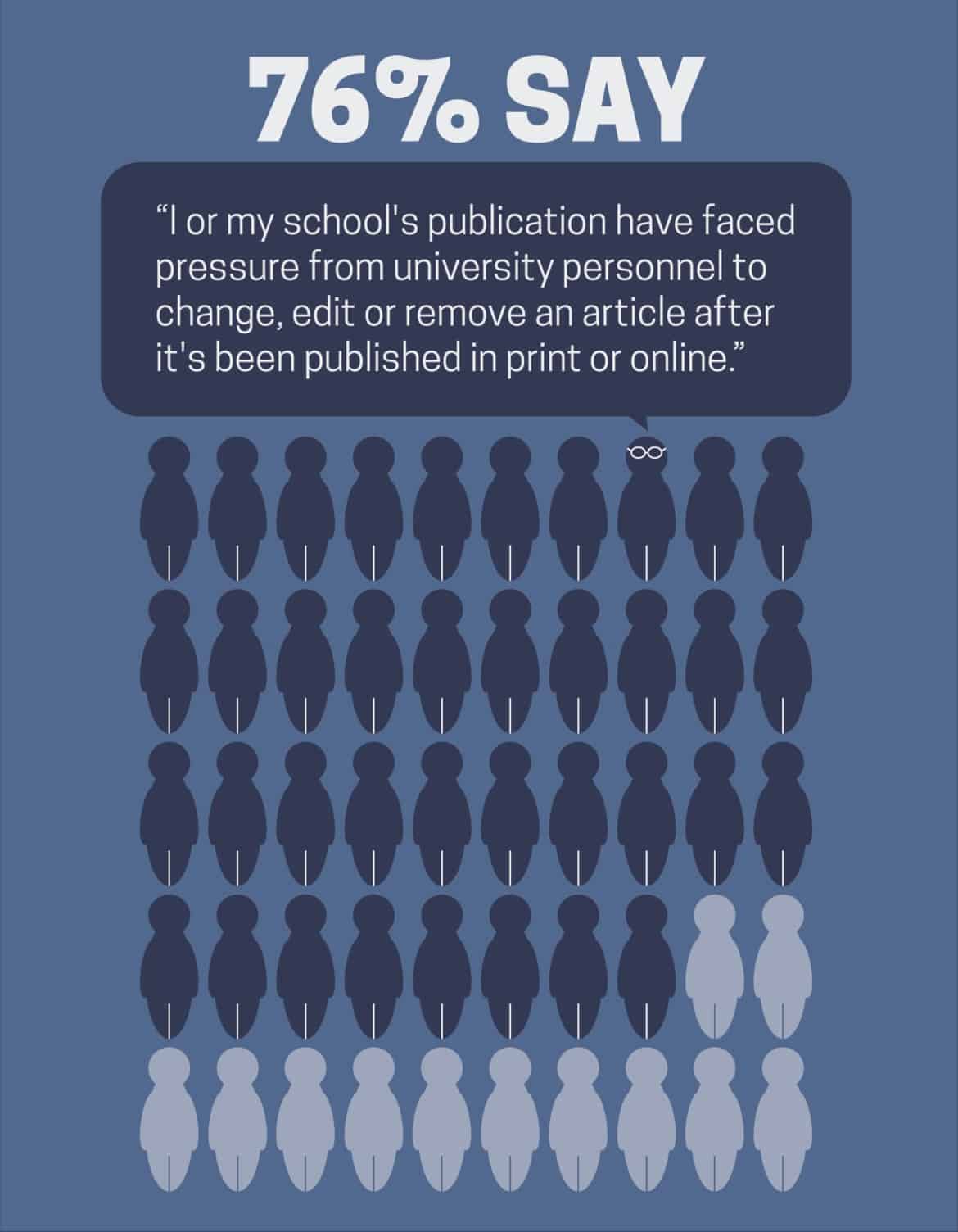

According to the study, released on May 1, more than 3 out of 4 student editors surveyed said school officials have pushed them to alter or pull a story — a number experts say would be much lower at public schools or even other private colleges.

Although some students expressed interest in finding a “balance” with administrators, others argued the findings shed light on pervasive censorship policies that contravene the journalistic values they learn in their classes and could adversely impact their future prospects in the field.

“It began as an independent project to persuade our school to change its policies,” said Cassidy Grom, head of the SPC and former co-editor-in-chief of her campus newspaper. “But when we saw the data, we decided to go public with it.”

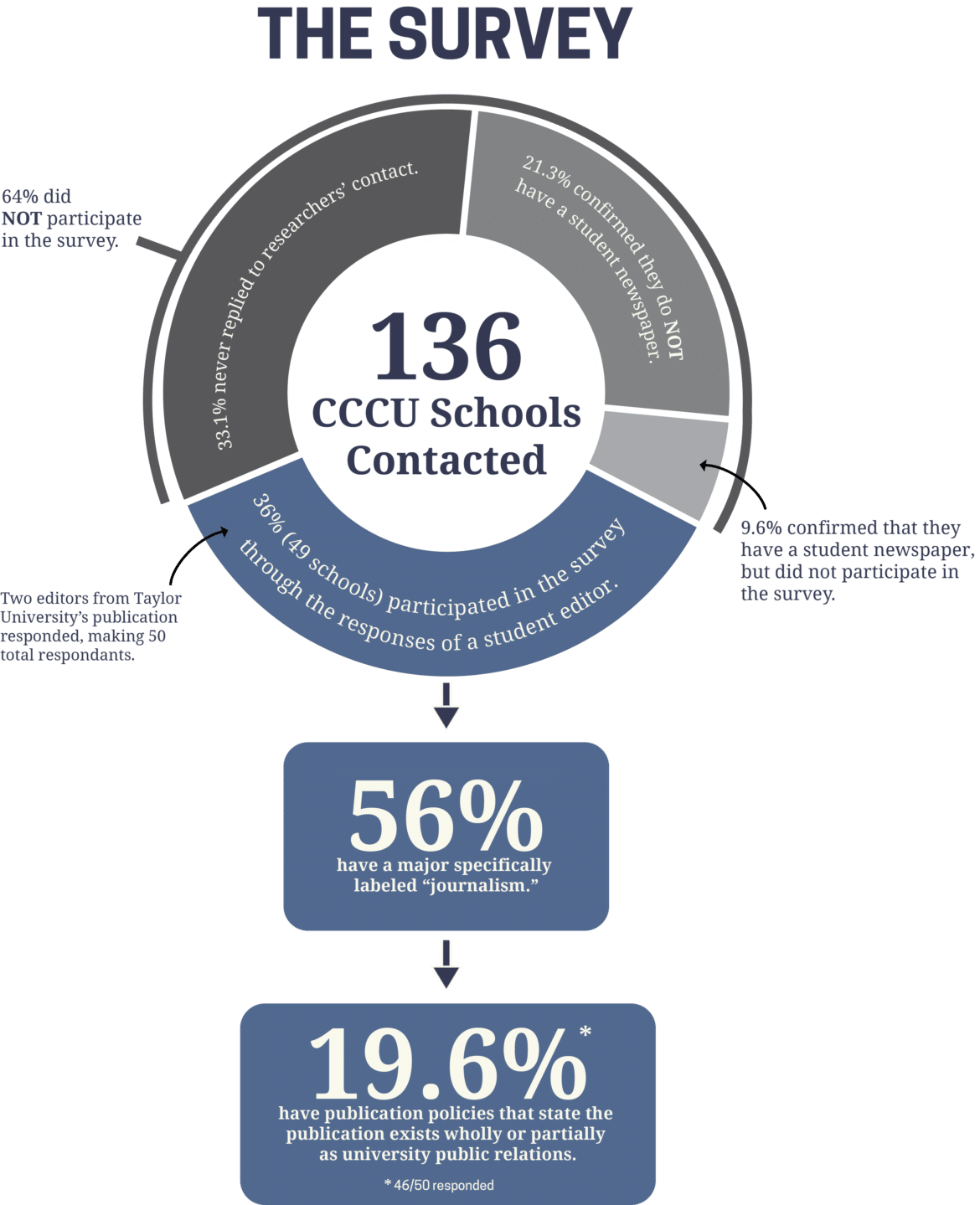

Graphic courtesy of ISPU Student Press Coalition designer Ellen HershbergerSurveyors reached out to student newspaper editors at 136 schools affiliated with the Council for Christian Colleges and Universities in the United States. (CCCU says its members represent “more than 150” schools in the U.S. and Canada). Including Taylor, 49 schools participated in the study, which was conducted through an online questionnaire after editors were contacted directly.

Graphic courtesy of ISPU Student Press Coalition designer Ellen HershbergerSurveyors reached out to student newspaper editors at 136 schools affiliated with the Council for Christian Colleges and Universities in the United States. (CCCU says its members represent “more than 150” schools in the U.S. and Canada). Including Taylor, 49 schools participated in the study, which was conducted through an online questionnaire after editors were contacted directly.

As for the more than three-quarters of respondents who reported facing pressure from the university to edit or remove an article after publication, “that is an entirely different number than we’d get at a public school — it’d be much, much lower,” said Mike Hiestand, senior legal counsel at the Student Press Law Center.

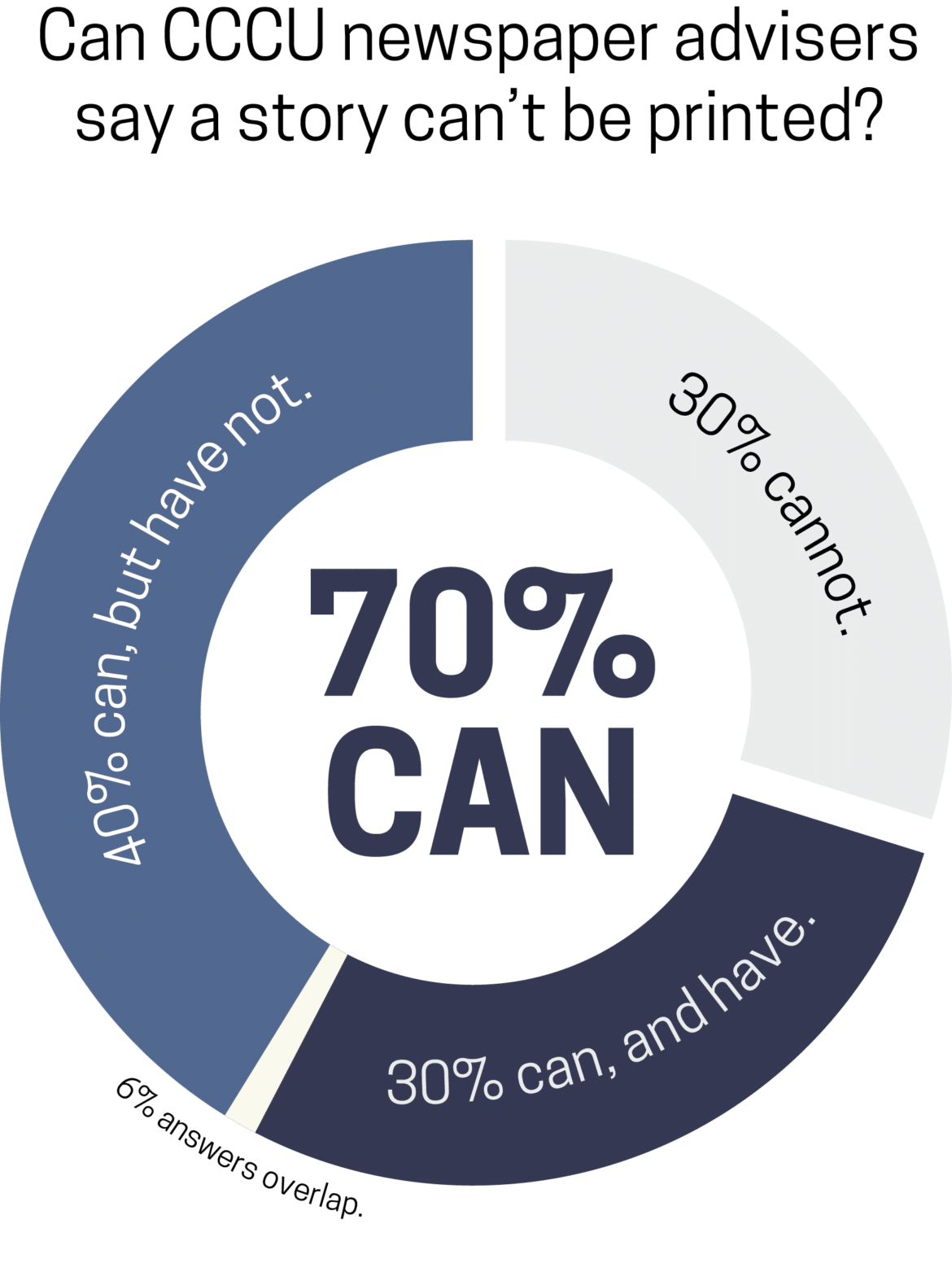

In addition, 72 percent said faculty advisers to their paper have the power to kill a story before publication online (70 percent for print), and 34 percent reported instances in which advisers have done so (30 percent for print).

In total, 49 percent of respondents agreed “it is fair to say” their “publication is censored” by someone who is not a student at some point in the editorial process, and 48 percent said university officials have asked student journalists to stop pursuing a story while it is in the research and writing phase.

Chris Evans, president of the College Media Association, said the numbers echo his organization’s own research on threats to independent journalism at universities. He said instances of censorship “happen all the time” at private colleges because they are in a different legal category than public schools.

“It’s tough because it’s perfectly legal at private colleges for administrators to censor because there is no guarantee of First Amendment protections,” Evans said.

A photo illustration of a newspaper in flames. Photo by Elijah O’Donell via Unsplash/Creative CommonsCatherine Ross, professor of constitutional law at George Washington University Law School who specializes in the First Amendment, said the survey’s findings aren’t surprising in the context of private schools. She said religious schools in particular have “understandable reasons” for exacting control over internal publications: Their faith-rooted nature means they prioritize specific spiritual teachings over the “freewheeling culture you would expect from a public institution.”

A photo illustration of a newspaper in flames. Photo by Elijah O’Donell via Unsplash/Creative CommonsCatherine Ross, professor of constitutional law at George Washington University Law School who specializes in the First Amendment, said the survey’s findings aren’t surprising in the context of private schools. She said religious schools in particular have “understandable reasons” for exacting control over internal publications: Their faith-rooted nature means they prioritize specific spiritual teachings over the “freewheeling culture you would expect from a public institution.”

But Ross said the level of oversight evidenced in the survey was an “outlier” compared with the vast majority of private colleges — which often emphasize free expression — and reminded her of the control wielded over public high school newspapers.

The data adds context to other allegations of censorship at Christian schools, which writer and Christian college graduate Sarah Jones argued in a recent piece for The New Republic constitutes an “invisible free speech crisis.”

In March, an assistant news editor at Liberty University — which is not a member of the CCCU — told Religion News Service that school President Jerry Falwell personally censored her attempt to cover a revival organized by faith leaders critical of him. She said the Liberty Champion, her campus paper, sometimes has articles pulled before publication, and she questioned whether it was “more a PR vehicle for the university than a newspaper.”

Graphic courtesy of ISPU Student Press Coalition designer Ellen HershbergerLiberty officials have not responded to requests for comment about the alleged incident.

Graphic courtesy of ISPU Student Press Coalition designer Ellen HershbergerLiberty officials have not responded to requests for comment about the alleged incident.

Robin Gericke, executive editor at The Asbury Collegian and a participant in the survey, also recounted an incident of what she described as censorship. When the Collegian published an interview with an openly gay alumnus about his experience at their school, administrators at Asbury University — a multidenominational institution grounded in “Wesleyan-Holiness theology” — confiscated the papers and locked them away, she said. Gericke says they were only released once the newspaper provided a letter proving they had express permission of the alumnus to publish the interview.

“That’s kind of our glory story,” she said, adding that she wants administrators to “stop seeing a newspaper as a PR piece and start seeing it as actual journalism.”

Asbury officials did not respond to requests for comment, but the newspaper’s faculty adviser confirmed the papers were at one point “secured.”

For those who would argue for greater freedom for student journalists at Christian colleges, the survey raises concerns about funding and control. Nearly 20 percent of respondents said their newspaper officially exists wholly or partially as university public relations, and 88 percent are funded at least in part by the college itself.

But those who champion student journalists’ editorial independence were encouraged by one statistic: 88 percent of respondents said their advisers support journalists, even if the administration is critical of their work.

Gericke praised Bandy, the faculty adviser to her newspaper and an assistant professor of journalism at Asbury. He argued faculty oversight offers an educational experience for student journalists.

“I have supported the students very strongly when I feel like they have all the facts,” he said. “I can’t remember advising against running a story when that was the case.”

But he noted that “at the end of the day, I work for Asbury University,” and said some topics are bound to stir controversy in a conservative Christian environment, including pieces that deal with human sexuality.

Grom said Taylor University’s conservative Christian roots impact her reporting, and how the administration views journalism as a whole.

“I think that the root of some of this censorship is the idea that Christians should have their own culture, their own microcosm, that is separate from culture,” Grom said. “There is a belief that secular culture is dirty, especially the mainstream media, and reporters are just out to get the scoop.”

“I think that the root of some of this censorship is the idea that Christians should have their own culture, their own microcosm, that is separate from culture,” Grom said. “There is a belief that secular culture is dirty, especially the mainstream media, and reporters are just out to get the scoop.”

Ross, who also described herself as a First Amendment advocate as well as a law professor, expressed concern for students who want jobs outside Christian media.

“There is the question of whether (the control) undermines your education, and if you’re a journalism major, whether you’re getting a fair bargain,” she said. “If these colleges are going to operate so far outside the norms that generally apply to journalism, maybe they shouldn’t be offering journalism concentrations or make it clearer to their students the ways in which this experience is going to be unrepresentative.”

The survey shows that less than a quarter (24 percent) of respondents “absolutely” believe their school gives them the same freedom of the press that public universities give students.

Speaking of her own school, Gericke said the role of student editors at Christian colleges is ultimately a “balance” between student views and “the people paying for our paper and our scholarships and our stipends.”