Rabbi Jeffrey Myers leads a gathering in Hanukkah songs after lighting a menorah outside the Tree of Life synagogue on the first night of Hanukkah, Dec. 2, 2018, in the Squirrel Hill neighborhood of Pittsburgh. A gunman shot and killed 11 people while they worshipped on Oct. 27, 2018, at the temple. (AP Photo/Gene J. Puskar)(RNS) — Hanukkah is meant to mark the victory of the Jewish people over religious oppression.

Rabbi Jeffrey Myers leads a gathering in Hanukkah songs after lighting a menorah outside the Tree of Life synagogue on the first night of Hanukkah, Dec. 2, 2018, in the Squirrel Hill neighborhood of Pittsburgh. A gunman shot and killed 11 people while they worshipped on Oct. 27, 2018, at the temple. (AP Photo/Gene J. Puskar)(RNS) — Hanukkah is meant to mark the victory of the Jewish people over religious oppression.

But in the days and weeks leading up to Hanukkah, which began Sunday (Dec. 2), many Jews have felt defeated as a steady wave of anti-Semitic incidents roiled the country.

Last week, a psychology professor arrived at Columbia’s Teachers College on New York’s Upper West Side to find swastikas spray-painted red in the foyer to her office.

Two weeks ago, a mural honoring the 11 victims of the Pittsburgh synagogue massacre was defaced on the campus of Duke University in Durham, N.C.

And the week before that, a man got up during a performance of “Fiddler on the Roof” in Baltimore and shouted “Heil Hitler” as the audience ran for the exits, afraid gunshots might follow.

These episodes, and numerous others not reported widely — such as a Houston synagogue fire now being investigated as arson — have alarmed Jews and other Americans. As they celebrate an ancient military victory, in which a band of Jewish rebels rose up against their Greek-Syrian oppressors and rededicated the temple in Jerusalem, many are still reeling from Pittsburgh’s Tree of Life synagogue shooting.

The October massacre, which killed 11, has been called the deadliest anti-Semitic attack in the nation’s history. But even before that, incidents of anti-Semitism were breaking records. In its most recent report, the Anti-Defamation League found that the number of anti-Semitic incidents rose nearly 60 percent in 2017 over 2016, the largest single-year increase on record and the second highest number reported since ADL started tracking incident data in the 1970s.

For many American Jews, the flurry of anti-Semitic incidents is a reminder of the stories told by their parents and grandparents of Europe in the dark days before the Holocaust.

And a new survey by the Claims Conference, an organization that compensates Holocaust survivors with funds received from Germany, found that 58 percent of Americans believe something like the Holocaust could happen again.

A Star of David that is part of a tribute mural was vandalized with a swastika on the campus of Duke University in Durham, N.C. Photo by Olivia Levine via FacebookBut are things really that bad?

A Star of David that is part of a tribute mural was vandalized with a swastika on the campus of Duke University in Durham, N.C. Photo by Olivia Levine via FacebookBut are things really that bad?

Most anti-Semitism watchers say no.

Worrisome as these incidents are, they are a sign that anti-Semitism persists but not cause for full-scale alarm.

“It’s clear there’s always been anti-Semitism in the U.S. because anti-Semitism doesn’t just go away,” said Jill Jacobs, executive director of “T’ruah: The Rabbinic Call for Human Rights.”

What’s changed, she said, is that “it’s become more socially acceptable to express it.”

Just when this wave of Jewish hate re-emerged is a matter of debate. The rise of white nationalism, white supremacy, neo-Nazis and other extremist groups may be one reason. The election of President Obama, the first African-American to occupy the White House, may have jolted white nationalists from their slumber, experts said.

But President Trump’s cultivation of a mostly white base of supporters, and his attacks against immigrants, asylum seekers, Muslims and foreigners, generally, may be enabling bigots to come forward, said Deborah E. Lipstadt, professor of Holocaust studies at Emory University and author of the upcoming book “Antisemitism: Here and Now.”

“People on the far right have been emboldened and have gotten what I call a ‘wink, wink, nod, nod’ from the highest levels of government and the president of the United States,” said Lipstadt.

But Lipstadt and others caution against seeing anti-Semitism as an exclusively right-wing phenomenon.

Activists on the left have also been accused of anti-Semitism. Last year, a lesbian pride parade in Chicago ejected three people carrying pride flags emblazoned with a Jewish Star of David. Earlier this year, a Washington, D.C., city councilman espoused a conspiracy theory that Jewish financiers control the weather. And in October, two instructors at the University of Michigan declined to write letters of recommendation for two Jewish students applying to study in Israel, calling attention to the ongoing harassment many Jewish students face on campus.

“You’ve got to be honest and see the anti-Semitism next to you and not just on the other end of the political spectrum,” Lipstadt said. “That’s really important.”

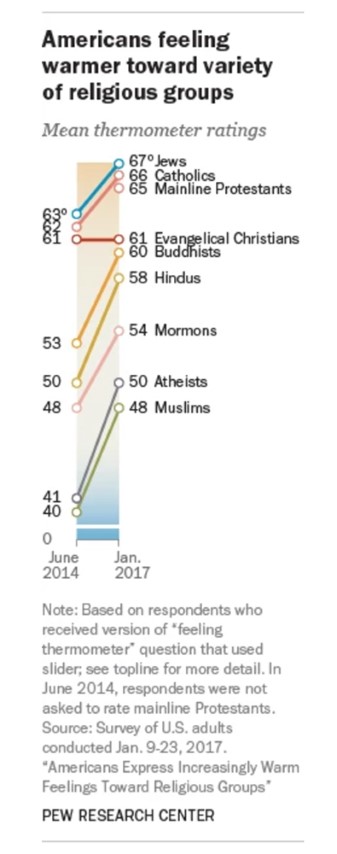

“Americans feeling warmer toward variety of religious groups.” Graphic courtesy of Pew Research CenterOverall, the fight against anti-Semitism has not been a partisan issue. Members of the U.S. House of Representatives’ Task Force on Anti-Semitism are split evenly between Republicans and Democrats. And after the Pittsburgh shooting, the House unanimously approved a bipartisan resolution condemning the synagogue attack.

“Americans feeling warmer toward variety of religious groups.” Graphic courtesy of Pew Research CenterOverall, the fight against anti-Semitism has not been a partisan issue. Members of the U.S. House of Representatives’ Task Force on Anti-Semitism are split evenly between Republicans and Democrats. And after the Pittsburgh shooting, the House unanimously approved a bipartisan resolution condemning the synagogue attack.

And though a striking number of white nationalists ran for office in the 2018 midterms — including some blatant anti-Semites and Holocaust deniers, all running on the Republican ticket— nearly all of them lost.

Far from reviling Jews, most Americans have warm feelings for them. A 2017 Pew Research survey “feeling thermometer” found that Jews and Catholics continue to be among the groups that receive the warmest ratings. Half of U.S. adults rated Jews at 67 degrees or higher on the 0-to-100 scale. (Muslims scored at 48.)

“We don’t have the anti-Semitism problem that France does, or Germany or Belgium or Hungary or Poland,” said Ira Forman, former U.S. special envoy to monitor anti-Semitism from 2013 to 2017, and now a visiting professor at Georgetown University and senior adviser on anti-Semitism to Human Rights First.

Forman thinks there’s one big difference between Europe — where more than 28 percent believe Jews have too much influence in business and finance, according to a CNN poll — and the U.S. He calls it “civil society.”

“This mechanism, which gives support to people who have been persecuted and can ostracize the haters, is a very powerful mechanism. We can build it up even further. It’s one of the important tools we have.”

Civil society is what led to an outpouring of interfaith services, in churches, synagogues and mosques, showing solidarity for the Jewish community after the Pittsburgh shooting. It led to multiple acts of kindness — from the $200,000 donated by Muslims to cover the cost of the funerals, to a San Francisco Sikh artist who created 150 menorahs and donated the profits to the local Jewish Community Relations Council.

Still, two days before Hanukkah started, Rabbi Eric Solomon and the staff of his synagogue — Beth Meyer Congregation in Raleigh, N.C. — spent the day in active shooter security training. Beth Meyer has beefed up security following the Pittsburgh shooting, as have most synagogues across the country, some of which have installed metal detectors at the door.

Solomon said he was grateful for the prayers, flowers and cards sent in the wake of the massacre. But in an op-ed in the local paper he said one more thing is critically needed: “You must raise your voice.”

Referencing the Book of Proverbs, he added, “Life and death are in the power of the tongue.”