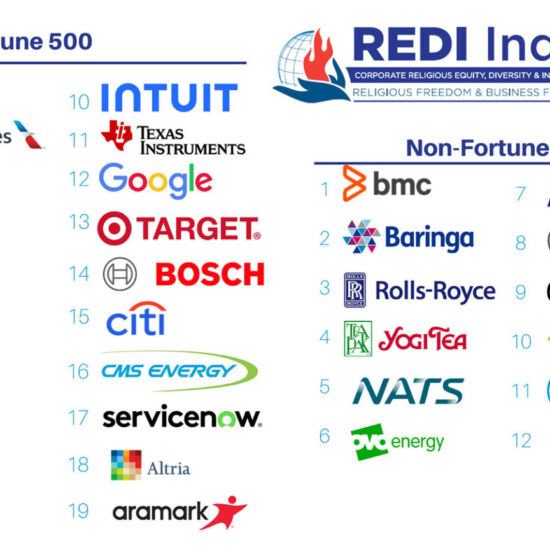

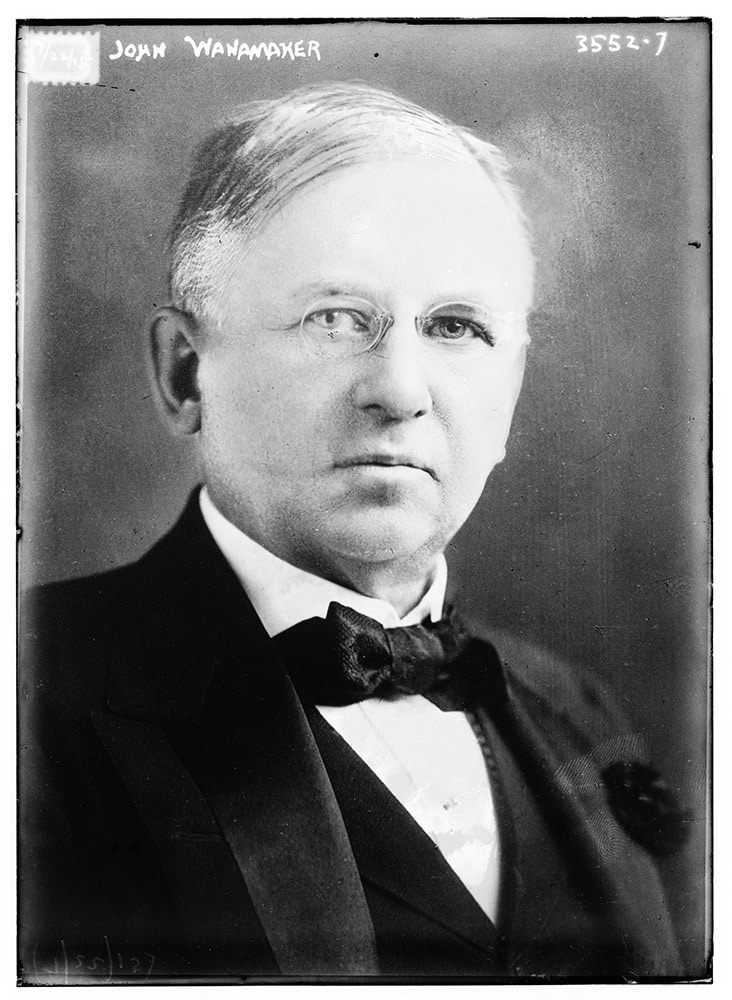

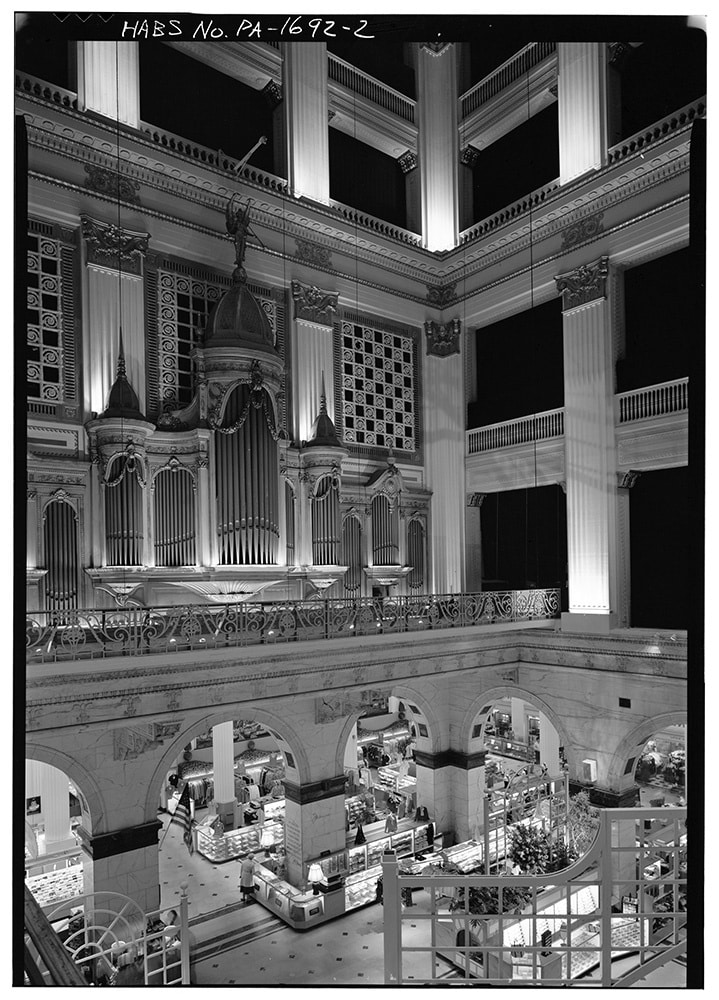

John Wanamaker, left, and the Grand Court interior of his original Philadelphia store, which is now a Macy’s. Photos courtesy of Creative Commons(RNS) — During his lifetime, John Wanamaker built two megachurches.

John Wanamaker, left, and the Grand Court interior of his original Philadelphia store, which is now a Macy’s. Photos courtesy of Creative Commons(RNS) — During his lifetime, John Wanamaker built two megachurches.

One tried to save souls.

Another sold clothes, jewelry and perfume.

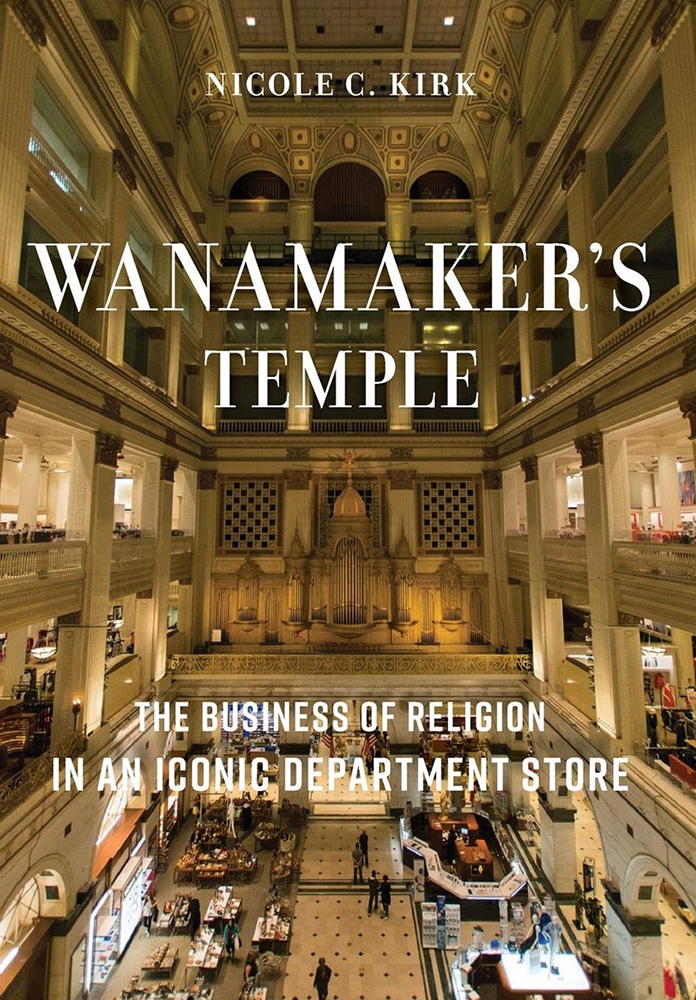

And the two worked hand in hand, said Nicole C. Kirk, an assistant professor at Meadville Lombard Theological School in Chicago and author of “Wanamaker’s Temple: The Business of Religion in an Iconic Department Store.”

Wanamaker believed “his business interests and his religious interests were not in conflict,” said Kirk, and he could integrate the two without compromise.

“Over and over, and not defensively, (Wanamaker) speaks about how he doesn’t see a conflict and they are mutually supportive,” said Kirk, a Unitarian Universalist minister and historian of religion.

Image courtesy of NYU PressWanamaker put it this way, said Kirk: “The store will be my pulpit and they are part and parcel of each other.”

Image courtesy of NYU PressWanamaker put it this way, said Kirk: “The store will be my pulpit and they are part and parcel of each other.”

In their heyday, the two Wanamaker enterprises — department store and church — influenced the community, raised the living standards of thousands of employees and church members, and melded commerce and Christianity in a way not previously seen in America, Kirk said.

His eponymous department store – now a Macy’s — in Center City Philadelphia contained a 10,000-pipe organ and presented religious-themed Christmas and Easter programs. His church, Bethany Presbyterian Church, drew thousands for worship.

Wanamaker, who also served four years as postmaster general of the United States, was foremost an evangelical Christian who melded faith and works, specifically the working of his retail empire. While building the first department store in Philadelphia, he also funded the growth of the city’s first megachurch, which featured a range of social services undergirded by a strong evangelistic outreach. He offered young male employees of his store guidance through a YMCA-like program aimed at promoting spiritual discipline. All employees could spend a summer vacation at a church-run resort, albeit with strict behavioral codes.

The merchant was so famous for his public expressions of faith he was satirized as “Pious John” in newspaper cartoons. But the ridicule did not deter him from his mission to blend faith and commerce, using his wealth to fund the YMCA, where he had worked before going into retail, as well as the Salvation Army, whose U.S. leader, Commander Evangeline Booth, became a close friend.

Washington University professor Leigh Eric Schmidt said Wanamaker’s philosophy was a “wider” version of the “gospel of wealth” popular during that era.

“It was good to make money and spend it on the right causes, education or the Sunday schools, or moral uplift, or missions,” said Schmidt. “It was good to attain that kind of wealth if you stewarded your wealth in the right ways.”

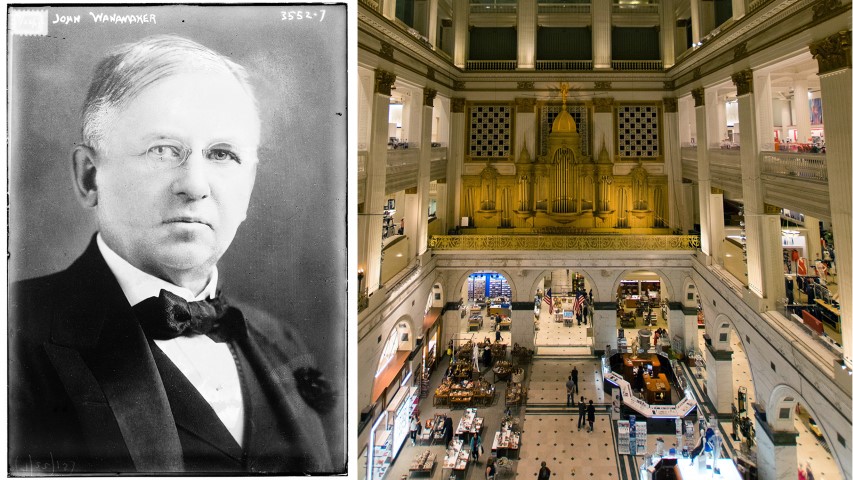

John Wanamaker in 1915. Photo courtesy of LOC/Creative CommonsKirk said Russell Conwell, a clergyman best known for establishing Temple University, was a huge influence on Wanamaker. Conwell, she said, preached about the “Acres of Diamonds” available to those who work hard and seek out opportunity.

John Wanamaker in 1915. Photo courtesy of LOC/Creative CommonsKirk said Russell Conwell, a clergyman best known for establishing Temple University, was a huge influence on Wanamaker. Conwell, she said, preached about the “Acres of Diamonds” available to those who work hard and seek out opportunity.

She termed Conwell’s message an early iteration of today’s “prosperity gospel,” proclaiming that God will financially reward those who are faithful.

The wearing of religion “on one’s sleeve,” said Vanderbilt University professor James Hudnut-Beumler, was more conspicuous with Wanamaker than contemporary businesses such as fast-food chain Chick-fil-A or Hobby Lobby would now indulge. The chicken sandwich company, for example, closes its franchises on Sundays but keeps its owners’ faith largely private.

Wanamaker’s faith, by contrast, was more “in your face,” said Hudnut-Beumler.

Wanamaker’s store had a sacred Christmas display, complete with a creche, and religious displays at Easter. And no one boycotted them, said Hudnut-Beumler.

“Not even Chick-fil-A was as in your face with its ‘performed Christianity’ as was Wanamaker at the height of his powers,” he said.

Hudnut-Beumler said Wanamaker’s public faith “is so much a reflection of the Protestant moment in American religious history when people either were Protestant of a certain sort or had to accommodate themselves to evangelical Protestantism.”

Today, you can be philanthropic,” he said. “You can lead with a big heart, you can even be paternalistic, but you had better not infringe on other people’s religions if you want to have a huge market share.”

Along with his overt religiosity, Wanamaker “presaged the mid-20th-century evangelical revival led by people such as Billy Graham” through his interdenominational work, according to Hudnut-Beumler.

The Grand Court of the John Wanamaker Store in Philadelphia. Photo courtesy of LOC/Creative CommonsWhen revivalist Dwight L. Moody came to Philadelphia, Wanamaker remodeled the hall in which Moody conducted his campaign to make it more suitable. Some churchmen viewed the Salvation Army as “competition,” Hudnut-Beumler said, but Wanamaker endorsed its work of evangelizing those in poverty or addiction.

The Grand Court of the John Wanamaker Store in Philadelphia. Photo courtesy of LOC/Creative CommonsWhen revivalist Dwight L. Moody came to Philadelphia, Wanamaker remodeled the hall in which Moody conducted his campaign to make it more suitable. Some churchmen viewed the Salvation Army as “competition,” Hudnut-Beumler said, but Wanamaker endorsed its work of evangelizing those in poverty or addiction.

“The fascinating thing about Wanamaker is, even though he belongs to a ‘tribe,’ Presbyterians, he’s so much bigger than his tribe, when it comes to Christianity,” Hudnut-Beumler said.

Kirk, whose next project is a biography of George Pullman, a railroad magnate and Unitarian, said she was struck by the reaction of people when she mentioned her study of Wanamaker’s life and religion.

“What was exciting about this research was how people responded to my saying I was working on a book on Wanamaker,” she said. “Their eyes would light up and they’d tell me a story about a family member that worked there, made a career out of it, or going to Center City and seeing the displays. There is this grand nostalgia for the great American department store that no longer exists.”