Jeremiah Chapman prays during a 16th Street Baptist church service on Dec. 10, 2017, in Birmingham, Ala. (AP Photo/Brynn Anderson)

(RNS) — Change is part of the journey into young adulthood, the years in which Americans are most likely to move, attend college and change jobs. For the past 12 years, LifeWay Research, an evangelical firm that conducts research on the intersection of faith and culture, where I am executive director, has been studying how these changes affect the faith of young Protestant Christians. The results of our new survey are being released today.

It turns out, perhaps not surprisingly, that as they grow, today’s youth are also rethinking where church falls in their lives.

What may surprise many church leaders, however, is the increase in those who say politics played a role in their walking away.

The rate of Protestant young adults leaving church has not changed statistically in the last decade, when their departure was first quantified systematically, but some reasons for leaving have shifted — including more pointing the finger at the political positions of the church.

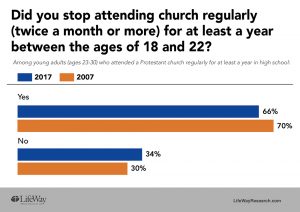

“Did you stop attending church regularly (twice a month or more) for at least a year between the ages of 18 and 22?” Graphic courtesy of LifeWay Research

In the new study, a follow-up to one released in 2007, LifeWay Research surveyed online 2,002 young adults about why they stayed or why they stopped attending church regularly. Today 66 percent of young adults who attended a Protestant church regularly for at least a year in high school stop attending regularly for at least a year between ages 18 and 22.

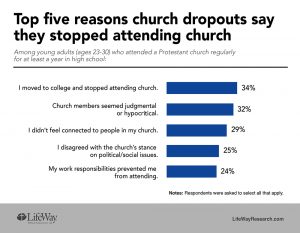

Those who left were given a list of possible reasons from which to choose, and they could choose as many as they liked. Many reasons for no longer attending regularly were repeated from the earlier study, plus several reasons related to the student ministry at the church that were not explored in 2007. In all, 55 potential reasons for leaving were offered, and the average young adult stepping away from church selected seven.

The top 10 reasons look similar in many ways to the 2007 study. Moving to college, work responsibilities, and judgmental or hypocritical church members all made the top five reasons in both surveys.

But the reason that saw the greatest growth, jumping to the fourth most frequently given, was, “I disagreed with the church’s stance on political/social issues.”

In 2007, 15 percent of church dropouts gave this as a reason. Today, 25 percent say it played a role.

The proportion of young adults leaving Protestant churches is statistically unchanged, so we cannot conclude that politics is causing a new segment of people to leave the church. We can say, however, that political views expressed in churches are having more influence on people who are leaving.

“Top five reasons church dropouts say they stopped attending church” Graphic courtesy of LifeWay Research

This research should cause reflection on what has changed in the last 10 years and what needs to change today.

Inevitably, many outside and some inside the church will say the solution is to never mix religion and politics. A majority of Americans, our previous research has found, think the church should be silent on politics.

It could be easier for church leaders to not talk about politics at all. In fact, 30 percent of Protestant churchgoers don’t know if their political views match the majority of those around them in their congregation. But this misses the opportunity to show how God cares about the ills of our society.

Indeed, the conflict between religion and politics didn’t arise in the last presidential election campaign. Among Jesus’ own disciples, there were at least two who had conflicting political persuasions.

Little is written in the Bible about Simon the Zealot, but his nickname indicates he had been actively involved in the opposition to the Roman government. Matthew, another disciple, known as a tax collector, had aligned himself with the Roman occupiers. We don’t know if those two ever agreed on politics, but we do know they worked together to build the church.

Since then, people from vastly different political viewpoints have followed Jesus together. Christians simply cannot ignore politics and follow Christ’s example.

Church leaders today can find room for political involvement that will not alienate the next generation. Students and young adults want a faith that is relevant to their entire lives, including their political lives. Telling teenagers that faith is irrelevant to real life will not keep them from leaving the church. It may hasten their exits.

Nor must churches shy away from biblical truths on controversial issues. Instead, church leaders should explore these truths further with teens. Talk together more, not less.

For churches today, however, the end game cannot be winning elections, passing laws or securing Supreme Court seats. It’s that kind of shortsighted perspective that led Jesus’ disciples to look for a political savior. Jesus demonstrated he was a different kind of savior; Christians must be a different kind of people.

Part of being different in this age of perpetual political battles is recognizing that not all political issues are created the same. What tends to divide us is not the goals we want to achieve, but how we want to achieve them. Virtually everyone wants to help the middle class, for instance, or to keep the country safe, but parties and politicians disagree on the best way to get there. Churches must discover which political distinctions are essential for Christians and which allow for disagreement.

Jesus’ teaching and other biblical writings repeatedly address issues such as taxes, inequalities, caring for the downtrodden, praying for leaders, obeying civil authorities, etc. Yet they rarely venture into the often contentious debates on the specifics of how governments were to operate.

This is important to keep in mind as church leaders think about those leaving the church. Teenagers and young adults are exploring, trying new things and pushing on social standards — just as previous generations did. They are forming opinions on immigration, guns, the environment, global intervention and numerous other topics.

Not all of their views will be shared by their elders. But as students explore, they are watching to see how older followers of Jesus Christ respond. Teenagers are highly attuned to inconsistencies and an unwillingness to listen to different political views. Both imply to them that God’s kingdom is not our primary allegiance.

Listening to them, on the other hand, demonstrates to teenagers that God is bigger than political differences and that a serious faith can handle all of life’s questions.

Listening can be hard when young adults take idealistic stands or think that the church should learn from them, but not vice versa. Churches have a choice, however: Either relentlessly toe a specific political party line, or make sure young adults know they are valued. Almost 3 in 10 young adults who stop attending regularly attribute this to not feeling connected to people in their church.

Teenagers aren’t likely to be fazed when others in church disagree with them, but they listen closely to see if their fellow church members will demean them or their position. If so, the student will feel judged and less connected to the congregation. A judgmental or hypocritical congregation was cited by 32 percent of young adults as contributing to their decision to stop attending regularly.

Students will notice, too, if only one political party is represented among those who attend a church. Half of Protestant churchgoers want to attend a church in which people share their political views. In a church filled with only people of one persuasion, the unstated but clear message to a young person who disagrees becomes, “You are not welcome here if you are not on our side of the political aisle.”

It’s common for young adults to be discovering their own priorities, and to leave the church, at least temporarily, while they do. If church leaders want them back, they have to ask themselves: Are they willing to love their young people more than they do their political opinions?