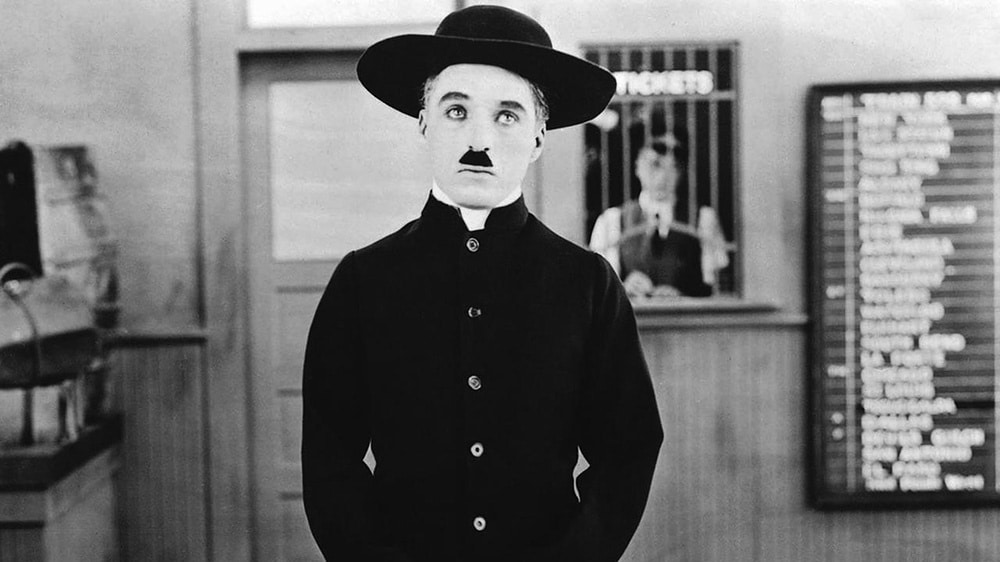

Charlie Chaplin portrays an escaped convict disguised as a chaplain in the film “The Pilgrim.” Photo courtesy of Creative Commons

WASHINGTON (RNS) — “Brief were my days among you, and briefer still the words I have spoken,” wrote Kahlil Gibran, in one translation of his best-selling spiritual classic “The Prophet.” “And though death may hide me, and the greater silence enfold me, yet again will I seek your understanding.”

Gibran died in 1931. His prediction that an author’s words can live on after his or her death has proved true. More than 9 million copies of “The Prophet” had been sold by the late-2000s, according to The New Yorker.

Now “The Prophet” is about to start another chapter in its literary afterlife. It’s among thousands of books, songs and films that entered the public domain on Jan. 1, 2019 — the first time that published works’ copyrights have expired since 1998.

“The Prophet” by Kahlil Gibran was first published in 1923. The work entered the public domain on Jan. 1, 2019. Image courtesy of Knopf Books

Originally published in 1923, the works were slated to enter the public domain — meaning others are free to adapt and otherwise use them — in 1999. But Congress extended the copyrights for 20 more years.

Among the trove that entered the public domain are other iconic 1923 works with religious content, including “The Pilgrim,” in which Charlie Chaplin plays an escaped convict posing as a minister; Universal Studios’ “The Hunchback of Notre Dame” starring Lon Chaney, which grossed $3.5 million (more than $50 million today); Cecil B. DeMille’s film “The Ten Commandments,” which he later remade on a grander scale in 1956; and George Bernard Shaw’s play “Saint Joan.”

Public domain allows contemporary creators to adapt works in a manner that would often surprise, if not disappoint, the original creators. Jane Austen couldn’t have known that her 1813 novel would inspire “Pride and Prejudice and Zombies.”

But public domain also can keep works — and their creators’ reputations — alive.

Entering the public domain isn’t the death of a copyright, according to Karyn Temple, acting register of copyrights and director of the U.S. Copyright Office.

“It is part of copyright’s lifecycle,” she said at a recent U.S. Copyright Office event at the Library of Congress, “the next stage of life for that creative work.”

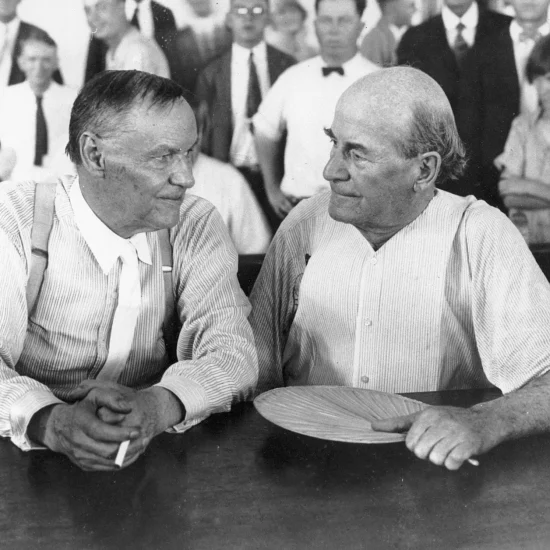

A scene from the 1923 Cecil B. DeMille production of “The Ten Commandments.” Photo courtesy of Creative Commons

Whitney Levandusky, attorney-advisor for public information and education at the Copyright Office, referred to public domain in terms of a “cultural afterlife.”

Dov Weiss agrees.

“Even people that do not believe in an actual afterlife, metaphorically use the term to describe books they write that will live on forever or children that they bear,” said Weiss, associate professor of religion at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. (Weiss was not a speaker at the event.)

Two of the more prominent artists whose religiously themed works entered the public domain this month would likely have enjoyed the notion that their works can be more easily revisited and adapted, scholars said.

A sculpture of Kahlil Gibran at a Washington, D.C. memorial to the Lebanese artist. RNS photo by Menachem Wecker

The Lebanese-American writer Gibran would have been “absolutely delighted that his work remains in print, in any format,” said Greece-based scholar and translator Robin Waterfield, author of “Prophet: The Life and Times of Kahlil Gibran.”

“He felt that writing and painting were what he had been put on earth for. He was part of a movement that saw art and spirituality as a source of redemption for the world, and the world sure needs redemption now.”

Notably, Gibran’s “Prophet” was non-denominational and thus can appeal to readers irrespective of their faith or spiritual backgrounds, according to Waterfield.

“Gibran’s basic message throughout his work was always, ‘You can be a bigger and better person. The universe is loving and large, and you can grow into it,’” Waterfield said. “You know that feeling when you first fall in love, how the whole future is contained in that first moment? That’s the kind of expansiveness Gibran wanted to foster.”

DeMille, an American filmmaker who died in 1959, is better known for his 1956 version of “The Ten Commandments,” a remake of his 1923 film.

But many directors have been inspired by the earlier version.

“Most famously was the shower curtain ripped down in ‘Psycho,’ which Alfred Hitchcock took from the original ‘The 10 Commandments,’” said David Blanke, author of “Cecil B. DeMille, Classical Hollywood, and Modern American Mass Culture, 1910-1960” and professor of history at Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi.

Filmmaker Cecil B. DeMille circa 1920. Photo courtesy of Creative Commons

Toward the end of DeMille’s film, a man shoots and kills a woman through a shower curtain — some 37 years before “Psycho” came out.

Blanke thinks that DeMille would like the idea of contemporary artists retooling his works and giving them a modern spin. DeMille often spoke of watching, as a child, beetle larvae emerge from water and transform into dragonflies.

“He used this metaphor repeatedly to suggest how the ‘afterlife’ was a world beyond the comprehension of the submerged beetle,” Blanke said.

DeMille was also very concerned about his personal legacy, and his decision to personally save his originals is the reason so many are well-preserved today.

“After studying his records for the past several years, one comes away from it knowing that he cared very deeply about the preservation of film in general,” Blanke said.