A new Pew study shows that religiously active people are generally happier. Photo courtesy of Creative Commons

(RNS) — People who are active in their religious congregations tend to be happier, a new Pew survey finds. But that advantage doesn’t extend to their waistlines.

In a large meta-analysis of 35 countries, Pew researchers found that religiously active people around the world report a range of desirable health and social outcomes. They vote and volunteer more. They also smoke and drink less than the nonreligious or those who rarely attend.

The study, “Religion’s Relationship to Happiness, Civic Engagement and Health,” builds on a growing mountain of literature linking religion and health. That literature has mostly found that religions seem to contribute to overall health, though there are obvious exceptions.

Perhaps most notably, religious participation does not appear to encourage weight loss or regular exercise.

In 19 of the 35 countries, actively religious people are as likely as any other to be fat. They are also less likely to exercise.

Harold Koenig, one of the foremost experts on religion and health, and a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Duke University, said the correlation is particularly true in the U.S. among African-Americans and ethnic groups.

Religious people, he said, “are encouraged to eat. And the kinds of meals people eat in church fellowship groups are high-calorie ribs and fried chicken.”

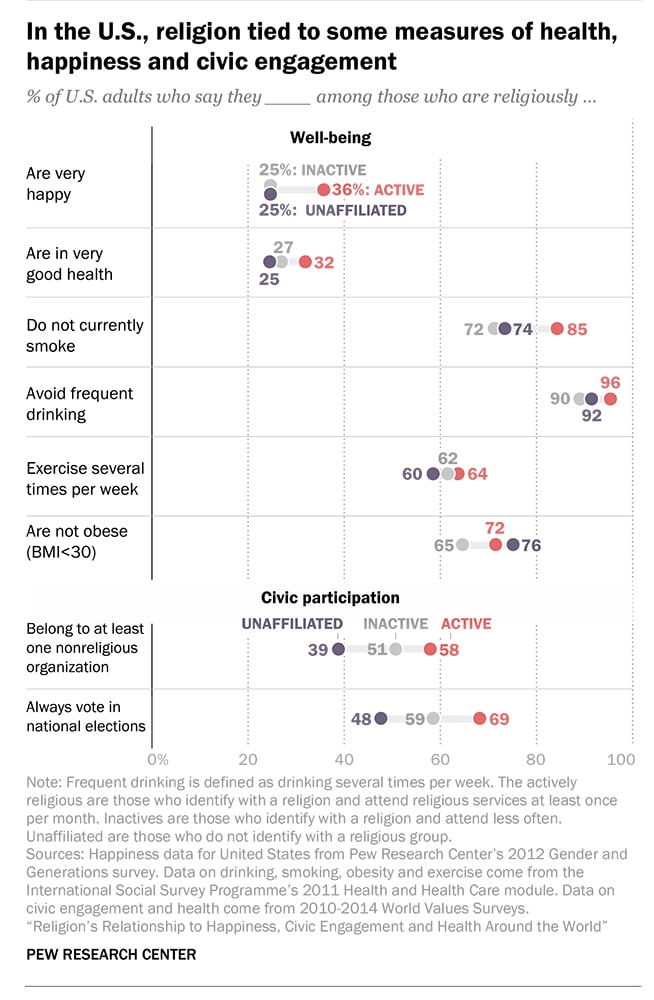

“In the U.S., religion tied to some measures of health, happiness and civic engagement” Graphic courtesy of Pew Research Center

In most countries, highly religious people are not more likely to rate themselves as being in very good overall health. The U.S. is among the exceptions. Thirty-two percent of Americans who are active in their religious congregations say they are in very good health, compared with 27 percent of their religiously inactive counterparts and 25 percent of nonreligious people.

The association between religion and happiness, however, is clear-cut: In every country studied, people who are active in religious congregations tend to be happier than those who attend infrequently or not at all.

Thirty-six percent of actively religious U.S. adults describe themselves as very happy, compared with just a quarter of other Americans. In Australia, 45 percent of actively religious adults say they are very happy, compared with 32 percent people who attend infrequently and 33 percent of people who never attend. In some countries the differences weren’t that statistically significant.

Pew researchers believe that it is not the religious affiliation that makes people happier, but the social connections that come with regular participation. They arrived at that conclusion since they found no meaningful differences in happiness between those who attend infrequently — but presumably still prize their religious affiliation — and those who never do.

“That suggests it’s really active participation in the social life of the religious community that drives these well-being gaps, not just identifying with a religion,” said Joey Marshall, a research associate at Pew.

The religiously active tend to also be civically engaged. In the U.S., 69 percent of the actively religious say they always vote in national elections, compared with 59 percent of those who are not as active and 48 percent of those who are nonreligious.

The analysis relied on crunching numbers from existing cross-national surveys conducted between 2010 and 2014 by the Pew Research Center and two other organizations: the World Values Survey Association and the International Social Survey Programme.

Analysts divided survey respondents into three groups: those who were active in religious congregations, those who were inactive but still claimed a religious identity and those who do not identify with any organized religion (sometimes called the “nones”).

The finding that in most countries regular participation in a religious community was also linked to higher levels of civic engagement suggests that friendship networks may be associated with making people happier.

Harvard political scientist Robert Putnam calls this “social capital,” because those friendship networks not only make people happier but also help people find jobs and build wealth.

Pew analysts took pains to point out that the numbers do not prove that going to religious services improves people’s lives. It could be that civic engagement drives people to be active in religious communities, or that those activists are happier to begin with, rather than becoming happier because of their faith commitments.