Photo illustration by Timothy Hale/Creative Commons

(RNS) — A “Safe Churches and Ministers” video features a woman recalling how, from the first day she worked as an interim youth minister, the senior pastor of a prestigious Baptist church began making inappropriate sexual advances.

“Is her story familiar?” asks a narrator after the woman describes too-long hugs, inappropriate conversations and an offer to share a hotel room at a denominational meeting.

“Have you considered that Michelle’s story can happen in churches today?”

The eight-minute video from the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship is an example of how some Baptist organizations, faced with a #MeToo culture and news accounts of sexual abuse by clergy, have worked to prevent and react to allegations that arise in local churches.

As the Southern Baptist Convention grapples with how to address sex abuse allegations, three other Baptist networks that split from it over the years have already taken steps to educate and assist their congregations should they face similar situations.

Religion News Service asked 10 Baptist groups if they had any policies or procedures related to sex abuse allegations. One of those three that responded was the American Baptist Churches USA, formerly known as the Northern Baptists, from which the SBC split when the more conservative denomination began in 1845 as it defended slavery. A fourth, the historically black National Baptist Convention, USA, also responded by Wednesday (March 6).

ABC communications director Bridget Lipin told RNS that “every ABC region has a policy and procedure for responding to allegations of sexual misconduct of clergy, and these policies include care for the abused.”

She added that regional gatherings of American Baptist Churches have offered sex abuse prevention training “that includes keeping spaces safe for children.”

The denomination also has a database of convicted or credibly accused offenders who have been affiliated with it, Lipin said.

“Persons who have been flagged because of clergy misconduct are indicated as such in a national database that all regions have access to,” she said.

The NBCUSA said it “does denounce sexual abuse in the church and in our country” but its independent congregations determine policies about their leaders.

“To date we have not been involved in any cases where any survivor of sexual abuse has requested any specific outreach from the convention,” the NBCUSA said.

The NBCUSA said it does not have a database of convicted or credibly accused offenders but it recommends criminal background checks be used by member churches before they hire staffers. It said it has planned training for its June conference on preventing the hiring of sex offenders; NBCUSA lawyers have also been asked to create forms to guide churches’ hiring processes.

“The National Baptist Convention does not allow anyone to serve in a leadership capacity within the organization that has been credibly accused of any sexual impropriety when that information comes to its attention,” it said.

The Southern Baptist Convention and other Baptist organizations that have autonomous congregations have said that their structures had prevented having a database.

David Pooler, an associate professor of social work at Baylor University. Courtesy photo

But David Pooler, a scholar who has written about clergy sexual abuse and interviewed survivors, said he believes databases are nevertheless necessary.

“We need to have lists and databases ’cause I honestly don’t know how else to record and have a record of the fact that someone has perpetrated this abuse and misused their position,” said Pooler, an associate professor of social work at Baylor University.

Pooler has served on a task force in which Cooperative Baptist Fellowship and Baptist Women in Ministry focused on addressing clergy sexual misconduct. He said the local autonomy of Baptist churches is fraught with quandaries when an abuse situation arises.

“I just think that there are multiple challenges to the very system that created the problem and enabled the problem and may have been complicit in the problem,” he said. “The very vulnerability that created the problem is now then trying to solve it.”

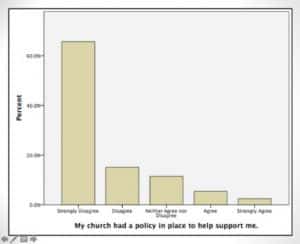

“My church had a policy in place to help support me.” Graphic courtesy of David Pooler

Pooler’s research has shown an absence of policies to assist survivors. In his 2015 survey of 165 survivors of clergy sexual abuse, Baptist women were among the three most predominant groups.

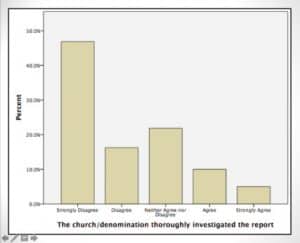

Overall, more than 60 percent of respondents strongly disagreed with the statement “My church had a policy in place to help support me.” Close to half strongly disagreed with the statement “The church/denomination thoroughly investigated the report.”

The other two Baptist groups that responded to RNS were the Alliance of Baptists and the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship. Both split from the Southern Baptist Convention in the latter part of the 20th century over differences about biblical interpretation and women’s ordination, which the SBC does not support.

““The church/denomination thoroughly investigated the report” Graphic courtesy of David Pooler

The Alliance of Baptists issued a 2018 “Statement on Sexualized Violence” that provided a link to a website where survivors could share their stories.

Toya Richards, the Alliance’s communications specialist, said the Tucker, Ga.-based faith group has clergy sexual misconduct policies that apply to chaplains and pastoral counselors that it endorses.

She said it does not have a database of convicted or credibly accused offenders.

“During our 32-year history there have been no cases of sexual abuse reported to the Alliance that would warrant any official action,” she said.

Richards said the Alliance offers training to chaplains and counselors around the time of the Alliance’s annual meetings.

“With deep awareness of the dangers inherent in the Baptist principle of local church autonomy, the Alliance strives to raise awareness of the need for accountability for clergy and church leaders regarding sexual misconduct,” she said. “The necessity for each church to establish safe sanctuary policies within the local congregation and to enact those policies is critical.”

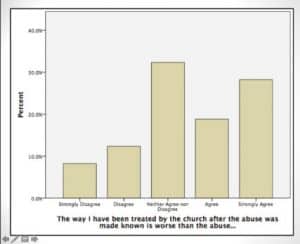

“The way I have been treated by the church after the abuse was made known is worse than the abuse…” Graphic courtesy of David Pooler

The Cooperative Baptist Fellowship formed the task force with Baptist Women in Ministry in 2016 that has included pastors, victims, scholars and attorneys. They have helped create a package of resources, in English and Spanish, that includes videos that explain the terminology of abuse and share survivors’ stories. The package also includes guidelines for creating policies about computer and social media use and for mobilizing a response team to respond to allegations.

Stephen Reeves. Photo courtesy of Cooperative Baptist Fellowship Photo

Leaders of the partnering organizations said they chose to focus on abuse of adults in churches because child protection policies are more prevalent.

Stephen Reeves, who coordinates CBF’s advocacy and partnerships, said the Decatur, Ga.-based fellowship does not have a database of convicted or credibly abused sex offenders who might have been affiliated with the organization.

Although the hiring of ministers happens at the local level, national leaders are nevertheless mulling possible next steps.

Pam Durso. Courtesy photo

“We’re currently working on that,” Reeves said, “on trying to figure out a system where credibly accused folks would be somehow flagged, or otherwise people would have notice of those accusations.”

Pam Durso, executive director of Baptist Women in Ministry, served as the narrator in the video. She said the resources she and Reeves have developed often lead to personal, private one-on-one responses from victims.

“I have never once done a presentation on clergy sex abuse — I’ve never once done it —without a response of ‘This happened to me’ or ‘This happened in my church or in my family,’” she said.