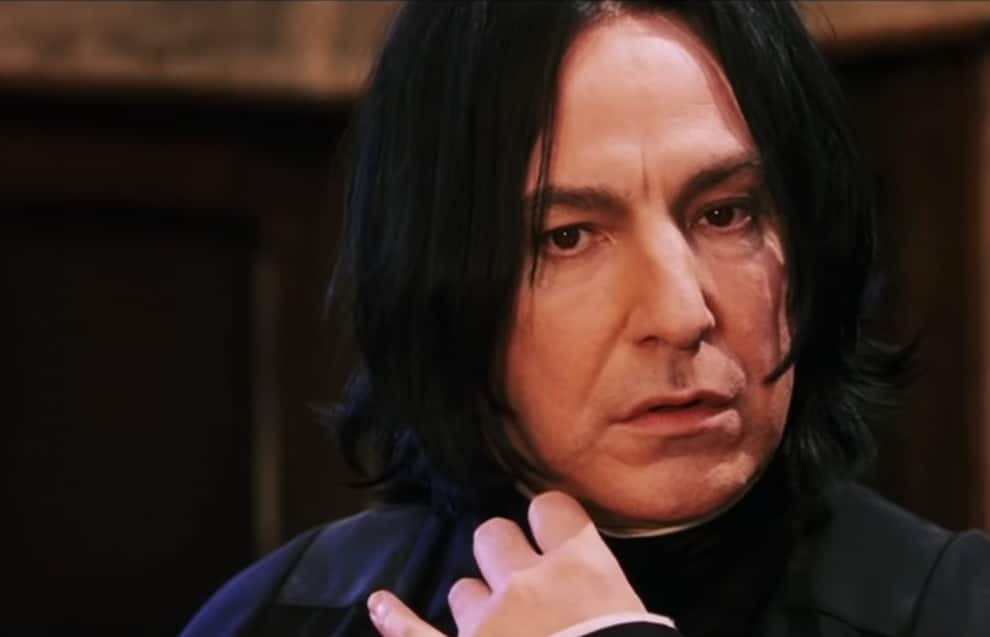

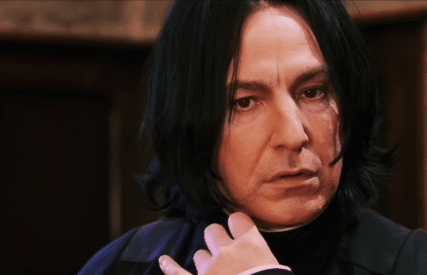

Alan Rickman as Severus Snape. Screengrab via Warner Bros. Pictures/YouTube

Masters voice I can heard (sic) loud and clear. I know when I do wrong, I know when he is pleased.

The way I see things is that we tend to limit ourselves, our believes (sic), our understanding, our willingness… due to what? Society? Because people tend to be afraid of what they don’t understand!?! Oh well, your all’s loss, my gain! Does that make me sick? No more so then (sic) others! .. MY MASTER!!!! (…) I stand where I stand, and ever so proudly

The above was written in the mid-2000s by a blogger who called herself Rose, who, along with a few close internet friends, was part of a tiny but culturally significant pack: online Harry Potter fans devoted to the veneration of one exalted character in J.K. Rowling’s wildly successful young adult fantasy series: Severus Snape.

Snape, the grumpy, antiheroic potions teacher at Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry, may be an odd choice for religious veneration. And the “Snapewives,” as this small, mostly female subset of fans called themselves, were hardly representative of fandom, even online fandom. But the phenomenon of Snapewifeism can tell us a lot about the way contemporary pop culture and contemporary religious culture have become increasingly fused among the eclectic, “DIY” culture of the spiritual-but-not-religious “nones.”

The intense, emotionally wrought subcultures like Snapewives defined internet fandom in the late 1990s and early 2000s. They laid the groundwork for geographically disparate but like-minded people to come together into “tribes.”

Unlike the generations that have come before us, we millennials grew up able to seek out “our people” without leaving our homes. As Buffy devotees, Harry Potter fans, or gamers, we weren’t limited to the tribal communities we lived in — our neighborhood, our city, or our local churches. These physical realities were for us, far more than for any previous generation, optional: one choice among many.

The proliferation of internet fan culture, with its emphasis on participation and creative repurposing of original texts, has created in millennials a broader sense of ownership over what we consume.

There’s a straight line from Snapewives, whose adoration inspired romantic narratives about Snape, to the 2015 novel “Harry Potter and the Methods of Rationality,” a sprawling, serialized epic of fan fiction published online over five years. The novel, devoted to all the different ways Harry Potter learns to improve his thinking patterns, emerged from a blog called Less Wrong founded by a rationalist named Eliezer Yudkowsky, a then-30-year-old self-taught artificial intelligence researcher in Silicon Valley.

“Harry Potter and the Methods of Rationality” has remained among the most popular “gateways” of users to the rationalist movement, and Yudkowsky has attracted funding from other Silicon Valley denizens such as PayPal founder and Trump supporter Peter Thiel for the blogger’s Machine Intelligence Research Institute, which attempts to counter the threat artificial intelligence may pose to humankind.

Other features of fan communities have bubbled into popular consciousness as well. A 2014 argument over so-called “ethics in video game journalism” and the need for more diverse characters in games began in obscure corners of the online world but erupted into mainstream media as the controversial #Gamergate, exposing the harassment aimed at Anita Sarkeesian, a video game critic whose advocacy for greater inclusivity in the gaming world unleashed thousands of internet trolls.

It’s easy to trace the 4chan-based alt-right of 2016 and the tech-savvy, reactionary hordes of (mostly) men seeking to battle perceived “social justice warriors” back to the online trolls and harassment threats of Gamergate.

But to merely condemn the poisonous precincts of Web culture is to miss the significance of the fan-fiction dynamic, which now pervades the Millennial mind, notably when it comes to religion.

If the printing press heralded a unilateral form of consumption — somebody writes and prints a book; we passively read it — the Internet transformed our consumption of texts and even visual media into malleable pieces that could be reimagined, reinvented. Often these inventions were thinly veiled erotic encounters between the author and a literary stand-in for the author’s beloved, but as a body of literature they were more akin to, say, ancient orally-told epics.

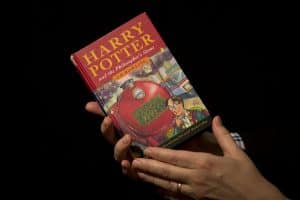

Sotheby’s director of the department of printed books and manuscripts Dr Philip Errington poses for photographers with a first edition copy of the first Harry Potter book “Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone” containing annotations and illustrations by author J.K. Rowling. (AP Photo/Matt Dunham)

Amid the multiplicity of voices and new customized narratives, the original author — Rowling or Tolkien or Joss Whedon — lost their authority, so to speak. One of the most striking cultural phenomena of recent years is the extent to which the Harry Potter fandom has turned on Rowling, proclaiming her unfit to manage her own fictional universe, especially since the publication of the final Potter book in 2007.

While by no means did all millennials participate in fan culture, its ethos has come to shape our whole online existence. You can see it in the creation and proliferation of “memes” — images endlessly and creatively repurposed and shared to satirize or sympathize with the day’s passing events. We scrupulously shape our own digital identities.

This sense of consumer ownership has, in turn, influenced millennials’ “mix and match” approach to spirituality more broadly. More and more of us feel entitled to pick and choose elements of our own spiritual and religious makeup, to write our own “sacred texts” from existing scripture or secular writings, to actively create our founding myths.

Our personal experience of a text — shaped through a dialogue with an intentionally chosen community — is more important than the “standard” interpretation.

Consider one of the most fascinating data points about the “religious nones”: a full 17 percent of them say they believe in the God as described in the Judeo-Christian Bible — yet they don’t identify with Judaism or Christianity.

In a sense, they’re the ultimate inheritors of the Snapewives’ cultural legacy. They believe in the validity of the book. They just think they can rewrite it better.