Sam Rockwell, left, and Taraji P. Henson, right, star in “The Best of Enemies.” Photo courtesy of Astute Films

(RNS) — In a darkened North Carolina parking lot, an angry black woman waves her Bible in the face of an equally angry, shotgun-wielding white man who has just told her his weapon speaks for him.

“This here does the talking for me,” she shouts in the new film, “Best of Enemies.” “Same God made you, made me!”

Not the most promising start for a buddy movie. And definitely not what Hollywood screenwriters mean when they say their protagonists “meet cute.”

Set in Durham in 1971, before the erstwhile textile and tobacco factory town became overshadowed by Duke University, the movie spotlights a dramatically unlikely — but nonetheless true — pairing: a local Ku Klux Klan leader named C.P. Ellis and Ann Atwater, a black community activist and single mother.

Through their friendship and shared Christian faith, the two demonstrated the possibility of reconciliation in the midst of a traumatic school integration controversy.

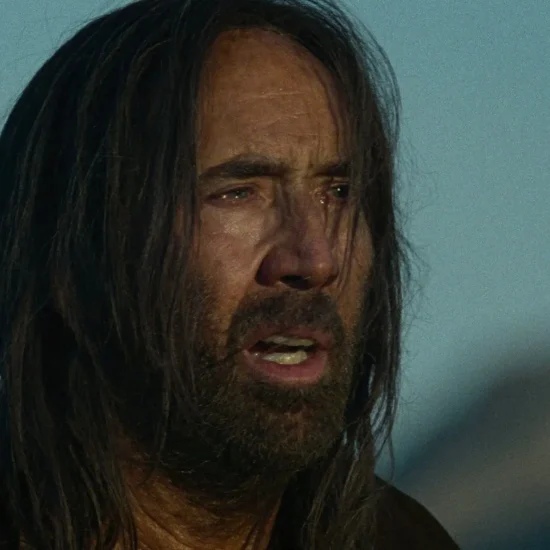

Based on Osha Gray Davidson’s 2007 book, “The Best of Enemies: Race and Redemption in the New South,” the film opens nationwide April 5 and stars Academy Award nominee and “Empire” star Taraji P. Henson as Atwater and Academy Award winner Sam Rockwell as Ellis. Anne Heche plays Ellis’ wife, Mary.

Sam Rockwell, left, and Taraji P. Henson star in “The Best of Enemies.” Photo courtesy of Astute Films

The film is firmly in the feel-good, “uplifting” movie genre – complete with a “Green Book”-ish resolution.

But while “The Green Book” featured what some African-Americans criticized as yet another cinematic “white savior,” the human savior in “Best of Enemies” is Atwater, a powerful black woman.

Despite its Best Picture Oscar, “The Green Book” also stirred controversy for inaccuracies pointed out by the family of its now-deceased African-American hero. By contrast, “The Best of Enemies” has the indisputable virtue of being accurate to both characters’ and their families’ recollections.

At the film’s premiere earlier this month in Durham, Henson said she was in awe of Atwater, who died in 2016.

“Ann was able to put her differences aside and see C.P. Ellis as a human,” the actress told the Duke Chronicle. “She was able to tap into his heart, and by doing that, she changed his heart.”

On the red carpet outside the restored Carolina Theatre in downtown Durham, Henson told a television reporter that the story of Atwater and Ellis was “a living testimony of love winning.”

And faith played a key role.

This odd couple bonded during an experimental 10-day encounter event between a group of black and white North Carolinians, held at a local junior high school. Funded by a federal grant and administered by the North Carolina AFL-CIO, Durham’s “community summit” on racial reconciliation was styled after the problem-solving seminars known as “charettes.” This style of seminar derives its name from its origin among French architects.

The two longtime antagonists were thrown together as the co-chairs of the charette, which was dubbed “S.O.S.” for “Save Our Schools.”

Sam Rockwell, left, and Taraji P. Henson, far right, star in “The Best of Enemies.” Photo courtesy of Astute Films

“Well, in the first five days of the meetings, we had a choir come in, a gospel choir, a church choir — to come in and do some singing,” Atwater recounted on NPR in 2005. “And C.P. was sitting there, and first he started clapping his hands. And he wasn’t clapping his hands even along with us; he would clap an odd beat. So I grabbed his hand and trying to show him how to clap along with us at the same time ’til we learned him how to clap.”

At the end of another session, according to the Raleigh News & Observer, “a black choir sang inspirational gospel tunes. Atwater knew Ellis was coming around when she caught him tapping his foot to the music.”

In the movie, the music incident unfolds quite differently than Atwater recalled in real life. In the movie, an angry white man responds to a suggestion that they include inspirational music in the program by saying, “Gospel music doesn’t have anything to do with this!”

Other real-life events were also far more dramatic than how they were depicted in the movie.

The two characters almost came to blows outside of a school during the integration crisis, Atwater told NPR’s Melissa Block.

“When I’d walk up to the school building, I had my white Bible in my hand,” Atwater said. “So I told C.P. we would see whose God would be the strongest, my God or his God. I always said if they’d said something to me, I was going to knock the hell out of them with my Bible.”

After battling for a decade over court-ordered school integration, they found that they had two things in common: poverty and powerlessness. Both had hard lives.

Ann Atwater, left, and C.P. Ellis, right, talk as they wait to see the premiere screening of the video documentary “An Unlikely Friendship” on Nov. 9, 2001, at the Tate-Turner-Kuralt building on the University of North Carolina campus in Chapel Hill, N.C. The documentary recounts the friendship that formed between Atwater, a poor civil rights organizer, and Ellis, a Ku Klux Klan member, in Durham during a racially charged period in the early 1970s. (AP Photo/Grant Halverson)

Atwater, a diabetic, barely survived on public assistance and her small salary as an organizer for a community organization called Operation Breakthrough. Ellis had to work two jobs to help support a child with multiple disabilities.

“I worked my butt off and never seemed to break even,” Ellis told radio host Studs Terkel in one of two appearances on his program. “They say, ‘abide by the law, go to church, do right and live for the Lord and everything will work out.’ It didn’t work out. It kept gettin’ worse and worse. I began to get bitter.”

Ellis had become an unenthusiastic churchgoer by the time he met Atwater. In the film, he is disconcerted when, sitting across from him in an assigned seat in the school’s cafeteria, she says a silent grace over her lunch.

Eventually, faith transformed both Ellis and Atwater.

“In church, the preacher says that if you want to be like Jesus you must be ‘born again.’ That really is the only way I can describe it,” Atwater wrote in a newspaper column. “We couldn’t be friends without forgiving one another.”

Many of Atwater’s family members, including her daughter, were in the audience for the film’s Durham premiere, which benefited the Rev. William Barber’s Poor People’s Campaign. The film’s first public screening was the previous morning for an audience of 600 Durham school students in honor of the school desegregation fight that is the centerpiece of the movie.

Not everyone was impressed by the friendship between Atwater and Ellis.

The two were subjects of articles from the New York Times to the Nation magazine, a book by Terkel, and a 2002 PBS documentary entitled “Unlikely Friendship.”

At the time, some skeptics saw the charettes and Atwater and Ellis’ joint speaking appearances as the embodiment of feel-good, wishful thinking.

But the pair was undeterred by such criticism.

“God had a plan for both of us, for us to get together,” Atwater said in her eulogy at Ellis’ 2005 funeral, following his death at 78 from Alzheimer’s, according to the Los Angeles Times obituary.