FILE – In this Feb. 1, 2017, file photo, the Supreme Court is seen in the morning in Washington. The Supreme Court has so far had little to say about Donald Trump’s time as president. That’s about to change. The justices’ first deep dive into a Trump administration policy comes in a dispute over the administration’s ban on travel from some countries with majority Muslim populations. (AP Photo/Jose Luis Magana, File)

(RNS) — Within the last two months, the U.S. Supreme Court has issued two important religious liberty decisions with strikingly similar facts and diametrically opposed outcomes. Both death penalty cases – Dunn v. Ray out of Alabama and Murphy v. Collier out of Texas – came to the court on emergency motions and therefore did not get the full briefing, oral arguments and public attention that most church-state cases enjoy.

These cases reveal important lessons about the challenge of protecting religious freedom in our pluralistic country, as well as the impact of public outcry and activism.

Both Domineque Ray and Patrick Murphy had been on death row for many years for heinous murders. Both were religious minorities – Ray a Muslim, Murphy a Buddhist. Alabama and Texas both permitted chaplains employed by the state to be in the execution chamber at the time of death, but excluded spiritual advisers who were not prison employees.

Dominique Ray (Alabama Department of Corrections via AP)

Since neither Ray’s imam, Yusef Maisonet, nor Murphy’s spiritual adviser, the Rev. Hui-Yong Shih, were prison employees, state officials had denied each inmate’s request to be accompanied by the chaplain of his faith at their deaths.

On Feb. 7, the Supreme Court allowed Alabama to go forward with its scheduled execution of Ray, without his imam at his side. The unsigned 5-4 opinion simply said that Ray had waited too long, raising his claim 10 days before his execution date.

Justice Elena Kagan, writing powerfully for the four dissenting justices, called the court’s decision “profoundly wrong.” Religious liberty advocates were shocked by the court’s decision, particularly when the justices have been expansive in their interpretation of free-exercise rights for Christian plaintiffs recently, in the Hobby Lobby, Trinity Lutheran Church and Masterpiece Cakeshop cases.

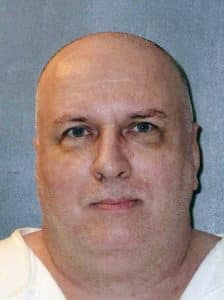

Patrick Murphy (Texas Department of Criminal Justice via AP)

Court watchers were equally surprised last week (March 28) when the Supreme Court abruptly changed direction in another case. The court delayed Murphy’s execution until Texas allowed a Buddhist priest to be present in the chamber. The unsigned single-paragraph decision was joined by seven justices, as Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Samuel Alito and Brett Kavanaugh all flipped their votes without explaining why they decided this case differently than Ray’s case less than two months prior.

Only Kavanaugh provided some rationale in his concurring opinion. Though he never mentioned the Ray decision, Kavanaugh referenced timing in a footnote, concluding that Murphy did not wait too long because he “made his request to the State … one month before the scheduled execution.”

But a cursory examination of the procedural history here shows that to be a flimsy argument: Murphy’s lawyers did not file their claim in federal court until just two days before the scheduled execution.

So what really accounts for the difference? The First Amendment’s “no establishment” and “free exercise” clauses, of course, had not changed; neither had the additional protections for prisoners provided by a federal statute called the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act. Both states have a policy permitting the presence of spiritual advisers in the execution chamber — an implicit acknowledgment that prisoners may have a need to practice that religion at the time of death. The First Amendment prohibits the government from then choosing which prisoner’s religious exercise will be accommodated. Kagan referred to this concept of “denominational neutrality,” while Kavanaugh called it “denominational discrimination.”

My question for the three justices who switched their votes: How could it be that Alabama’s policy did not discriminate against Muslims, while Texas’ policy did discriminate against Buddhists?

The traditional view has been that these nine jurists are insulated from pressure, but I think that is exactly what was applied by Kagan in her strong dissent and by religious liberty advocates in their resounding rejection of the court’s decision in Dunn v. Ray. I predict that we will look back on this pair of decisions as a case study in the power of advocacy, both within and outside the court.

That the court got it right on the next case is small solace, given the irrevocable harm to Ray.