Muslim and civil rights groups and their supporters gather at a rally against what they call a “Muslim ban” in Washington, on Oct. 18, 2017. (AP Photo/Manuel Balce Ceneta)

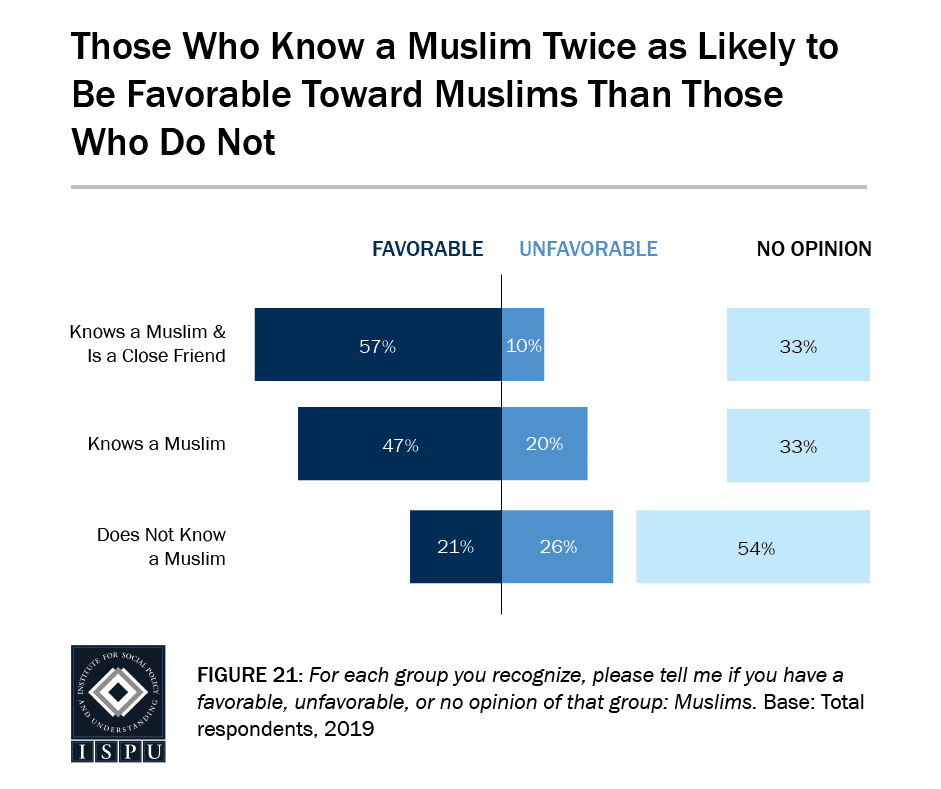

(RNS) — Americans who personally know a Muslim are more than twice as likely to have a favorable opinion toward Muslims than those who do not, according to a new report.

But researchers say that anti-Muslim attitudes is influenced by a host of factors, from personal and national politics to how much a person knows about Islam itself — but not one’s own religious affiliation.

The findings are part of this year’s American Muslim Poll, the fourth annual survey of U.S. faith communities conducted by the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding in Washington, D.C.

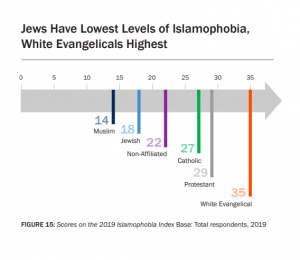

The poll found that Muslims remain the most likely group to report experiencing religious discrimination. The ISPU’s annual Islamophobia Index, which measures the public’s endorsement of five negative stereotypes about U.S. Muslims, inched upward from 24 in 2018 to 28 in 2019.

Graphic courtesy ISPU

American faith communities differ greatly in their attitudes toward Muslims, with Jews scoring the lowest in anti-Muslim sentiment (after Muslims themselves), while white evangelicals score the highest. More than half of Jews — the group most likely to know a Muslim personally — report having favorable views of Muslims, but just 20% of white evangelicals — the group least likely to know a Muslim — hold positive views of Muslims.

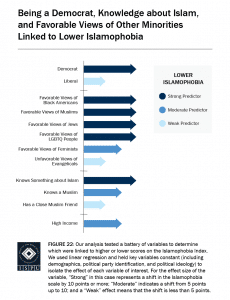

But a person’s faith appears to have no bearing on anti-Muslim sentiment, said ISPU director of research Dalia Mogahed. Instead, researchers found that partisan political ideologies are a much stronger predictor: Being a Democrat and identifying as a liberal is linked to lower Islamophobia.

“Religiosity doesn’t make people more or less likely to be Islamophobic, and in some ways that’s a good thing for those who want to improve the pluralism in America,” she said. “That means anti-Muslim sentiment can be changed, because political ideology is more malleable than religious beliefs.”

Graphic courtesy ISPU

Other factors that seem to contribute to lower levels of anti-Muslim bias, Mogahed said, include knowing a Muslim, knowing about Islam and holding favorable views of other minority groups.

“Personal interaction and affinity to a member of the community can go a long way to make people less likely to succumb to the toxic rhetoric that we’re hearing all the time,” Mogahed said.

About 21% of Americans who don’t know a Muslim at all report favorable views of Muslims. Among those who do know a Muslim, 47% report favorable views. And for those who have a close Muslim friend, that number jumps to about 57%.

“Polling data consistently reports that significant numbers of non-Muslims continue to report that they do not know a Muslim, let alone know much about Islam and Muslims,” noted John Esposito, director of the Bridge Initiative, a Georgetown University-based Islamophobia research project that partnered with the ISPU to produce the Islamophobia Index.

He pointed to a 2006 Gallup poll, which linked personally knowing someone who is Muslim with more favorable attitudes toward Muslims. That year, just 10% of those who said they personally knew someone who is Muslim reported that they would not want a Muslim neighbor. Among those who were not personally acquainted with a Muslim, that number jumped to 31%.

An even more powerful factor, the ISPU’s analysis found, is knowing something about Islam. Reporting knowing something about the religion itself was linked to scores at least 10 points lower on the Islamophobia Index.

Graphic courtesy ISPU

Researchers also found that Americans who hold favorable views of black people, Jews and LGBTQ people all tend to score at least 10 points lower on the Islamophobia Index.

“It really underscores that the same climate that is promoting Islamophobia is also promoting anti-Semitism and anti-black racism,” Mogahed said. She pointed to last week’s deadly attack on a synagogue near San Diego, where the shooter had also claimed responsibility for setting a nearby mosque on fire.

The research highlights concrete solutions for combating anti-Muslim hate, Mogahed explained. “It’s pretty clear. Make Muslim friends, learn about Islam, and work toward less bigotry in general.”

Unfortunately, said Esposito, recent depictions of Muslims, from President Trump’s demonization of Muslims to media coverage that links Islam with terrorism, have counteracted any progress Americans have made toward understanding Islam.

“You’ve got a president who’s saying ‘Islam hates us’ and putting in a Muslim ban, and you’ve got members of his administration who also have that kind of attitude,” Esposito said. “On top of that, you have disproportionate media coverage of what a small minority of extremists are doing, versus what the vast majority of Muslims around the world are doing. All those things feed this attitude in the country.”

Despite their grim treatment, the poll found that 33% of Muslims surveyed still reported feeling optimistic about the country’s general trajectory. Indeed, Muslims appear more satisfied with America’s direction than any other faith group or unaffiliated Americans surveyed, despite low rates of satisfaction with Trump’s performance as president.

Researchers attributed Muslims’ upbeat views to historic gains made by Muslim candidates during the midterm elections.

“The survey was right after two Muslim women were elected to Congress, and I think that historical event had boosted the sense of optimism among Muslims, even though they’re the most likely to disapprove of the president’s performance,” Mogahed explained.

Nonetheless, Muslims’ sense of optimism has taken a sharp hit since the ISPU’s 2016 poll, when 63% of Muslims said they were satisfied with the country’s direction.

“The underlying thread here, looking back at the previous studies, is that there’s a real problem of Islamophobia,” Esposito said.

The ISPU surveyed 2,376 Americans, including 804 Muslims and 360 Jews, throughout the month of January. The survey has a margin of error of 4.9 percentage points for Muslims’ responses.

Graphic courtesy ISPU

Graphic courtesy ISPU