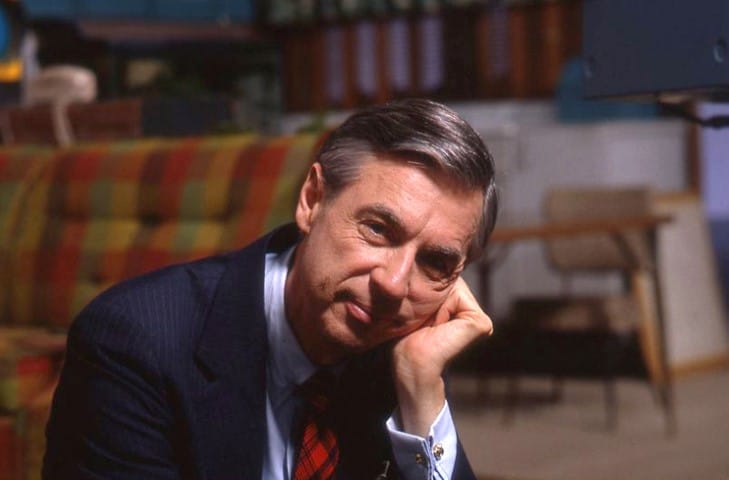

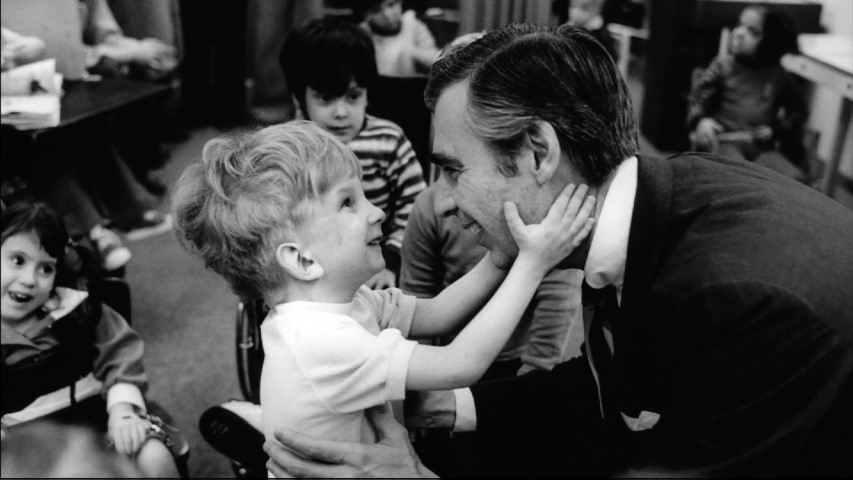

Fred Rogers on the set of his show “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood” from the film “Won’t You Be My Neighbor?,” a Focus Features release. Photo by Jim Judkis via Focus Features

(RNS) — In 1978, photographer Jim Judkis got a big break.

People magazine asked him to photograph Fred Rogers, the beloved public television host of “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood,” which was in its 10th year.

When he arrived to see Rogers, Judkis was nervous.

“You suddenly realize you’re in the presence of a known celebrity. I said, ‘Hello, Mister Rogers,’” Judkis said. “He smiled and reached out his hand to shake mine. He said, ‘Please call me Fred.’ It immediately put me at ease. Wow. He’s a normal guy.”

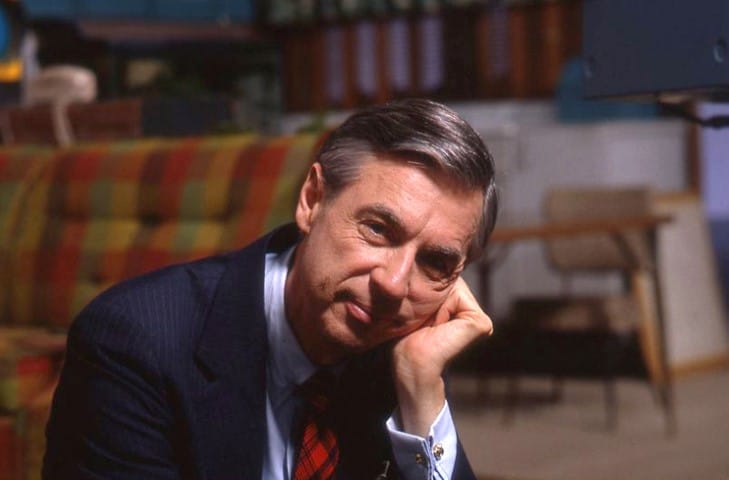

Over the next few decades, he photographed Rogers for People, The Philadelphia Inquirer’s Sunday magazine and Pittsburgh Magazine. Judkis’ most famous photo: an award-winning photograph he took of Rogers smiling as he looks, face-to-face, at a disabled child, who cradles Rogers’ face in his hands.

Fred Rogers meets with a boy who has a disability in the film “Won’t You Be My Neighbor?,” a Focus Features release. Photo by Jim Judkis via Focus Features

When the show went off the air, Judkis put the negatives of his photos of Rogers into storage and forgot about them.

His photos are now out of storage and on display at the Pittsburgh Jewish Community Center. Sixty of them appear in “The Loving Kindness of Fred Rogers” at the JCC through July 30.

The impetus for the display came three years ago, when producers making the HBO documentary “Won’t You Be My Neighbor” called Judkis and other Pittsburgh photographers, asking if they had any photos of Rogers.

Judkis said he’d look. But he wasn’t very excited. Rogers had died in 2003 and he didn’t know how much interest the documentary might generate. And didn’t really want to spend time sifting through his disorderly files of negatives.

But he eventually took a look.

“I realized: Whoa. I have a lot of images here,” he said of the three different photo shoots, with hundreds of negatives, he’d taken of Rogers. “Two hundred were pretty interesting and relatively different from each other.”

Even after the HBO producers had selected what they wanted, Judkis figured he had enough to exhibit.

In one photograph in the exhibit, Rogers sits on a floral-patterned couch in his WQED office with a notepad on his crossed legs. Rogers holds his glasses in his left hand, which also supports his head, while he writes with his right.

Over his right shoulder is a framed artwork bearing the Hebrew quote that is half of Song of Songs 6:3: “I am my beloved’s, and my beloved is mine.”

Judkis doesn’t know anything specific about the artwork.

“I didn’t have a clue what that said and meant,” he said. “I took the picture, because I saw it.”

Rogers, a Presbyterian minister, never talked about religion with Judkis, who wouldn’t have known that Rogers was ordained if he hadn’t been told or read it somewhere. He did know that Rogers knew Greek, though, and another photograph in the JCC exhibit shows Rogers sitting beside a card table bearing the very thick book “The Jerome Biblical Commentary.”

“He was a very, very scholarly individual. People think television, how intellectual is that? But he was many, many things,” Judkis said.

That a Jewish community center would focus on the Presbyterian minister, and that the latter would have a Hebrew quote on his office wall, may come as a surprise.

But Judkis records in the catalog that he felt a “sacred space” seemed to surround Rogers’ love for and interactions with every child he met.

Ron Symons, a Reform rabbi and senior director of Jewish life at the Pittsburgh JCC, says he was raised on Mister Rogers and his puppets.

The rabbi’s subsequent interest in midrash, often narrative-based rabbinic teachings, is “a direct result of those early days I spent sitting at the feet of Mister Rogers,” he wrote in the catalog for the exhibit.

The story, to Symons, has come full circle.

He works at the JCC, which is in the heart of the Squirrel Hill neighborhood “just 100 yards from the Sixth Presbyterian Church where Fred Rogers, a congregant there, learned about love of neighbor,” he wrote.

“And my desk faces due east: the same direction of Mister Rogers’ pew.”

Judkis said he’d recently spoken to the curator for the exhibit, who said the photos have been an encouragement to people in the community. The center is in the same neighborhood as the Tree of Life, site of a deadly attack last fall.

“The curator was telling people how these photos have uplifted the people walking through the Jewish Community Center, because they are sort of in PTSD mode and have been for a while,” Judkis said.

Judkis added that the show and the book include what he calls “off images.”

The “off images,” some of which are abstract or off-kilter, include the book’s cover image, which shows Rogers with his eyes closed.

“It’s an off picture, and I like that it’s included,” he said.

Judkis said the inspiration for including imperfect images came from Persian rugs — which sometimes include intentional flaws for religious reasons.

“One knot is wrong, because only God can make something perfect,” he said.