A halfpipe occupies the naive of the former St. Liborious Catholic Church in Old North St. Louis, which has been converted into SK8 LIborious in recent years. RNS photo by Bill Motchan

ST. LOUIS (RNS) — St. Liborius Roman Catholic Church in Old North St. Louis, listed on the National Register of Historic Places, was once called the “Cathedral of the North Side.” More recently, the massive structure has been appreciated on social media as “the sickest, gnarliest place ever.”

Bought a decade ago by four civic-minded St. Louis residents, St. Liborius is undergoing a transformation into a community arts center, but while the partners prepare to restore the German Gothic church, its nearly block-long nave has been turned into SK8 Liborius, a skateboarding park beloved by the local skater crowd for its challenging 12-foot ramp.

SK8 Liborius is perhaps not what architect William Schickel, who also designed the landmark Church of St. Ignatius Loyola in Manhattan, had in mind in the mid-1850s when he designed the stately red brick Gothic Revival structure.

But St. Liborius, like many retired but architecturally significant houses of worship, is surviving by converting to new uses that benefit their neighborhoods or cities in ways their original congregants might approve, but never imagined.

When old city-center congregations die or move out, they often leave behind two casualties: a unique building and a community anchor. To address both problems, architects and urban planners are increasingly applying innovative designs in an approach called adaptive reuse.

The former St. Liborious Catholic Church in Old North St. Louis. RNS photo by Bill Motchan

Adaptive reuse has become an answer particularly for those parts of aging cities that are revitalizing as millennials and retirees move downtown for inexpensive real estate, walkable lifestyles and craft beer. Suddenly, ornate, deteriorating office buildings, warehouses, former churches and synagogues offer architects acres of open floors with enviable amenities such as stained glass, intricate stonework and vast murals.

“If we want to preserve the integrity of our urban fabric, and we do, then finding a use for these beautiful older buildings is key to them remaining,” said Jeff Pelletier, principal at Board & Vellum Architecture and Design in Seattle.

For decades, as city centers emptied out, congregations migrated to the suburbs or exurbs. The moves usually produced one of four outcomes, according to Robert A. Simons, professor of urban studies at Cleveland State University and author of “No Building Left Behind: New Uses for America’s Religious Buildings and Schools.”

“The first option is to find another religious group to take it over; that’s the easiest,” Simons said. “The second is, if it can’t be salvaged because of market demand and the congregation can’t afford to continue paying for upkeep, you sell the land for another use, and that happens a fair amount of the time. The third is converting it to a community center or public space. They’re great, but expensive. And the fourth is converting it to housing.”

The second option has seen churches and synagogues become restaurants, performance spaces and even microbreweries in recent years. But regardless of the end product, houses of worship present some tough challenges, Pelletier said.

“There are structural concerns, seismic considerations and accessibility upgrades,” he added. “Ensuring that the new needs of the space work within the older structures often requires creative solutions. Houses of worship typically don’t have windows which match up with anything but a house of worship. Finding ways to make that work is always a fun design challenge.”

When the owners of St. Liborius Church acquired the building a decade ago, it was in bad shape, said Dave Blum, the principal of the ownership team.

Dave Blum inside SK8 LIborious in Old North St. Louis. RNS photo by Bill Motchan

“Our main goal was saving this building, and I know we’ve done that,” Blum said. “I can say with 100% certainty that if we’d gotten this building five years later than when we actually started working on it, we couldn’t have done it. When we started, it was on the edge of being unfixable and we pulled it back from the brink.”

In mid-May, Blum and his team were just completing an unexpected emergency tuckpointing that added $6,000 to the tens of thousands of dollars already spent on the project. Blum expects he and his partners will have to appeal to a developer for an infusion of capital at some point.

Blum has experience bringing old buildings back to life. In the mid-1990s, he helped restore and convert the 100-year-old International Shoe warehouse in downtown St. Louis into the City Museum, a celebration of whimsy and invention that attracts close to a million visitors a year.

“Preservation is the whole reason we’re doing it,” Blum said. “It’s undeniably an awesome structure and it’s a really great thing to preserve it. The skate park seemed to be a really great thing to put inside of this space. It’s a very unique melding of two things you usually don’t see together.”

But for Blum, SK8 Liborius is only a step toward drawing the neighborhood’s underserved children to the projected community center that will offer crafts like woodworking, printmaking and pottery.

“One of the hardest things about getting kids in the door of a community center is making them feel engaged,” he said. “That’s why skateboarding is the tip of the spear. It’s cool and kids will want to come here.”

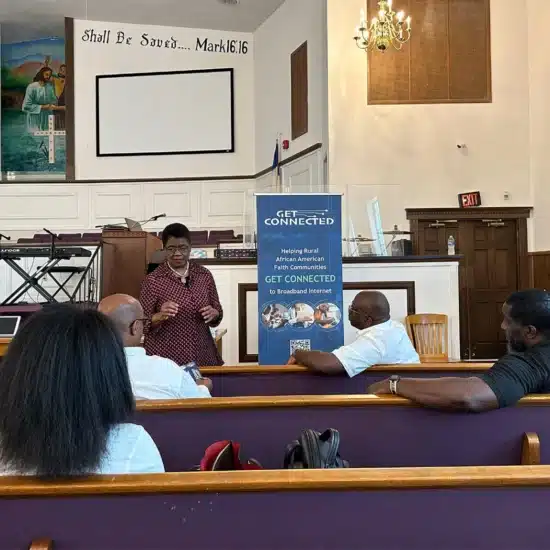

The Missouri History Museum Library and Research Center was originally the United Hebrew Congregation. RNS photo by Bill Motchan

St. Louis could be called a hub of adaptive reuse. One of the hottest cities for tech startups in recent years and named not long ago one of the country’s “25 coolest and most affordable places for millennials,” the city is studded with repurposed sanctuaries.

Eight miles southwest of St. Liborius, the Missouri History Museum Library and Research Center occupies what was from 1926 to 1989 the home of the United Hebrew Congregation. Founded in 1837, United Hebrew was the first Jewish congregation in St. Louis and west of the Mississippi River. When the congregation moved to the city’s western suburbs, the Byzantine-style structure with its distinctive 82-foot-diameter copper clad dome appeared to be threatened.

The congregation’s leadership had lucrative offers from developers who wanted to raze the building to capitalize on its valuable site, just a few blocks from Washington University and across the street from 1,300-acre Forest Park. But besides its architectural beauty, the building held too many memories for United Hebrew’s members to see it demolished.

Instead, the congregation sold the property to the Missouri Historical Society, a 150-year-old institution dedicated to saving the early history of the city and state from oblivion. In 1991, after investing $10 million to bring it back to original grandeur, the society reopened the United Hebrew building as a library and research center.

The Center of Creative Arts was formerly home to B’Nai Amoona, a prominent Conservative Jewish synagogue, near St. Louis, Mo. RNS photo by Bill Motchan

The Center of Creative Arts in University City, just west of St. Louis, was formerly home to B’Nai Amoona, a prominent Conservative Jewish synagogue. B’Nai Amoona moved 10 miles west in 1986 as its members migrated to the suburbs, leaving behind a noteworthy mid-century modern structure. It was built in 1950 and designed by Erich Mendelsohn, a pioneer in the art deco and art moderne movements.

Famous for his German expressionist-style Einstein Tower in Potsdam, Mendelsohn fled to England to escape the Nazis and in 1941 settled in the United States, where he helped foster what is known as the functional International Style. His first U.S. work was B’Nai Amoona in St. Louis. The original structure remains intact and is now in the process of a $28 million renovation and expansion effort.

Not least among the virtues of adaptive reuse is the way it helps cities to retain the spiritual impact of their houses of worship. Back in Old North St. Louis, Blum said, four nuns representing the Sisters of the Poor stopped by to check out the renovations to the stately former cathedral.

“We were holding their hands and leading them around on skateboards,” said Blum. “One was crying. They said they were so happy we were saving this building and that we were doing the Lord’s work.”