A rural church near Junction City, Kansas, in the early 1940s. Photo by John Vachon/LOC/Creative Commons

(RNS) — In her 2004 Pulitzer-Prize winning novel “Gilead,” Marilynne Robinson sketches a portrait of the Rev. John Ames, a small-town pastor in 1950s Iowa who is humble, self-aware, compassionate and devoted to his family and his congregation, and they to him.

Americans no longer hold clergy in such high regard, according to a recent poll, and even regular churchgoers are seeking counsel elsewhere.

A NORC/AP poll of 1,137 adults released this month shows that doctors, teachers, members of the military — even scientists — are viewed more positively than clergy. The less frequently people attend church, the more negative their views. Among those who attend less than once a month, only 42% said they had a positive view of clergy members — a rate comparable to that of lawyers, who rank near the bottom of the list of professions.

While frequent church attenders still hold clergy in high regard — about 75% viewed them positively — they give them only passing grades on a number of personal attributes. Only 52% of monthly churchgoers consider clergy trustworthy (that number drops to 23% among those who attend less than once a month) and 57% said they were honest and intelligent (compared with 27% and 30% among infrequent attenders).

“If you buy into the religious worldview, then the religious leader looks completely different than if you don’t buy into the religious worldview,” said Scott Thumma, professor of the sociology of religion at Hartford Seminary. “The perception from the outside is pretty bleak.”

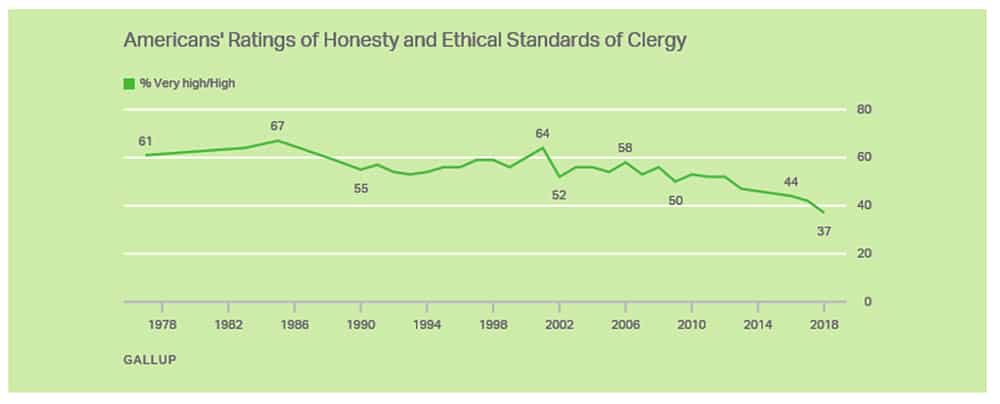

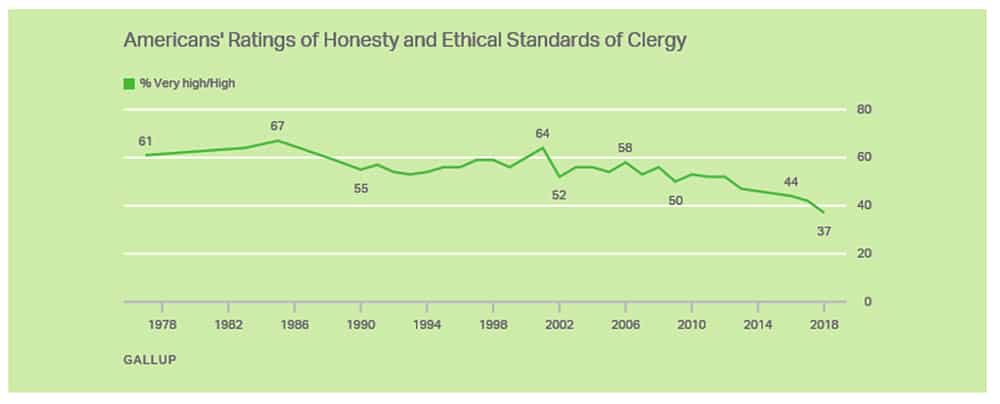

“Americans’ Ratings of Honesty and Ethical Standards of Clergy” Graphic courtesy of Gallup

The survey confirms previous studies. A 2018 Gallup survey of the public’s views of the honesty and ethical standards of a variety of occupations found that only 37% of Americans viewed clergy “very highly” (with 43% having an “average” view of clergy). It was the lowest Gallup recorded since it began examining occupations in 1977.

Historians say public attitudes about clergy have been waning since the 1970s, in tandem with the loss of trust in institutions after the Vietnam War and the Watergate scandal. The rise of the religious right and evangelical involvement in politics, beginning in 1979 with the creation of the Moral Majority, also played a role.

“What that did was create a certain polarization of views of the clergy,” said E. Brooks Holifield, professor emeritus of American church history at Emory University’s Candler School of Theology. “The televangelist scandals contributed to that. The sexual abuse among Catholics. All that created suspicion of the clergy.”

Perhaps as troubling, the NORC/AP poll, conducted May 17-20, showed that even monthly churchgoers don’t want clergy influence in their lives on a number of issues.

Clergy in a variety of denominations wear clerical collars. Photo courtesy of Creative Commons

Americans across the board said they didn’t want clergy input when it came to family planning, child rearing, sex, careers, financial decision-making, medical decision-making or voting. Clergy, the poll suggests, are growing irrelevant.

Asked more generally, “When making important decisions, how often have you consulted a clergy member or religious leader?,” 13% of monthly churchgoers said they did so “often,” and 31% said “sometimes.” By contrast, 56% said “rarely” or “never.” Among less-frequent churchgoers, 88% said “rarely” or “never.” (Two areas where clergy are still sought out by frequent attenders: marriage and divorce, and advice on charitable giving.)

One reason may be the growing educational ranks of people in the pews.

“There was a time when the clergyperson was the most educated person in the community,” said Mark Chaves, professor of sociology, religion and divinity at Duke University. “They had access to resources and knowledge. With increasing education in the general population, the role of clergy as experts might be decreasing.”

Society, too, has become more specialized. People will seek out professional therapists — a psychologist or a psychiatrist — rather than going to their pastor. They’ll seek out a financial planner if they’re they’re in debt or need investment advice.

A stained glass window of praying hands. Photo by Robert Adamski/Creative Commons

“There are people who are smarter, more competent, more equipped in certain fields, and that’s where we go for those sorts of answers,” said Kurt N. Fredrickson, associate professor of pastoral ministry at Fuller Theological Seminary.

Clergy, Fredrickson said, must recognize that churches today are often seen as fire stations — places to go when all else falls apart.

“I help younger pastors, pre-service, flip the power structure upside down; rather than seeing pastors as the top of the triangle I want to help pastors become servant leaders.”

While a pastor may not be the person to turn to for medical or financial advice, he or she may “walk alongside” the churchgoer who needs help and help point that person toward transcendent values, Fredrickson said.

To achieve that goal, he mentors pastors to have “humble convictions” and to be of good character.

The poll also showed that the majority of frequent and less-frequent churchgoers approve of women clergy and divorced clergy. Opinions on gay men as clergy were mixed. Only 40% of monthly churchgoers said they would welcome a gay man as their clergyperson, but 69% of less-than-monthly attenders said they would welcome such a person.

The NORC/AP poll has a margin of sampling error for all respondents of plus or minus 4.1 percentage points.