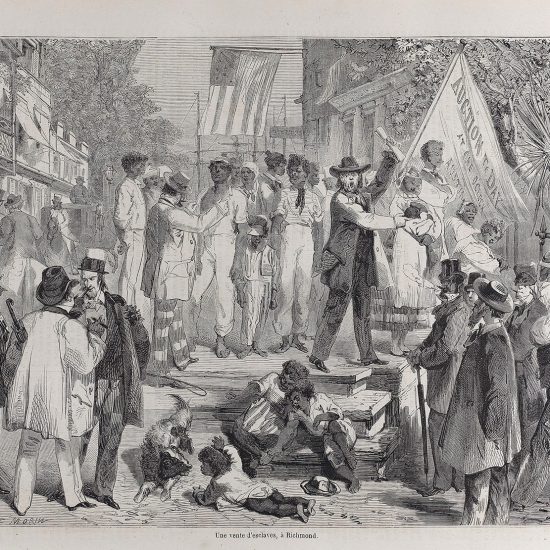

Baptist groups are engaged in a three-year effort called the “Angela Project,” named for the first enslaved African who arrived in Virginia 400 years ago on Aug. 20, 1619.

African-American novelist and playwright James Baldwin said, “History is not the past. It is the present. We carry our history with us. We are our history. If we pretend otherwise, we literally are criminals.”

With that in mind, black and white Baptists gathered together in Birmingham, Ala., in June. This year marks the 400th anniversary of the arrival of the first enslaved Africans in what is now the United States. Thus, the historically-white Cooperative Baptist Fellowship has partnered with two historically-black denominations — the National Baptist Convention of America and the Progressive National Baptist Convention — for a three-year effort from 2017-2019 called the “Angela Project,” which is named for the first of those enslaved Africans who arrived in Virginia on Aug. 20, 1619.

After meetings in Louisville, Ky., and Philadelphia, Pa., this year’s gathering occurred at 16th Street Baptist Church, which was the site of a 1963 bombing by white supremacists that killed four girls — aged 11-14 — as they were changing into choir robes for Sunday worship.

The church had served as a rallying point for the Birmingham civil rights activities led by Fred Shuttlesworth of Bethel Baptist Church. 16th Street Church sits across the street from Kelly Ingram Park, where earlier in 1963 police officers had used fire canons and dogs to attack peaceful protesters.

On June 19 — also known as “Juneteenth,” the oldest holiday commemorating the end of slavery in the U.S. — black and white Baptists gathered in that church to discuss racism. In the morning before the Angela Project, Baptist Women in Ministry also held its annual gathering at the church. Carolyn McKinstry, who had been at the church on the morning of the bombing and had just left the room where her friends were killed, preached about forgiveness. She described struggling with decades of depression and survivor’s guilt after the bombing.

Carolyn McKinstry (Brian Kaylor/Word&Way)

“In later years when I began to pray, when I learned about bold faith, when I learned about speaking what was in my heart, this is the point where I began to step away from darkness and into light,” she reflected. “I asked God ‘why,’ and God said, ‘Carolyn, you have to tell them, you have to tell everyone that only light dispels darkness. You have to tell them that only love dispels hate.”

McKinstry also noted that the lesson at church on the morning of the bombing had been “A Love that Forgives,” based on Luke 23:34. So, she encourages churches each year on Sept. 15 to preach “the message of forgiveness, the message of reconciliation.”

Lingering Consequences

A key focus of the Angela Project conference was on the continuing impact that slavery, Jim Crow laws, and segregation have today. Presentations focused on the massive wealth gap between blacks and whites, how that developed, and why reparations should be made to American descendants of slavery to right the historic injustices.

Joshua Poe (Brian Kaylor/Word&Way)

Joshua Poe, an urban developer and city planner, explained the problem of “redlining,” a practice of refusing to loan to someone because of where they live. Quoting from Baldwin, he argued it is important to know the history. He outlined the “racist origins” of this practice as city planners, banking institutions, and governmental officials forced blacks to live in certain parts of town and then refused to lend them money precisely because of where they lived. He noted that blacks were not only kept from gaining wealth but even treated as a drain on wealth for whites if allowed to move into the same neighborhood. These real estate policies resulted in preferential treatment for those living in whites-only communities, which allowed white wealth to grow from that assistance of governmental policies.

The intergenerational wealth — passed down to through generations — locked in the wealth disparity so that today whites, who make up about 63 percent of the U.S. population, hold about 90 percent of the wealth, while blacks, who are about 13 percent of the population, hold less than three percent of the wealth.

Poe urged those present to work to undo this disparity “with a sense of urgency because we should have done it decades ago.” Referring to a statement his grandfather taught him, he added that while the best time to plant a tree was 20 years ago, the next best time is now.

Joe Phelps (Brian Kaylor/Word&Way)

Joe Phelps, a longtime pastor in Louisville, Ky., spoke of coming to see his own white privilege. Although coming from a poor family, he now recognizes the opportunities his parents received solely because they were white, such as the chance for his dad to work in a factory where only whites were employed and the receiving of a loan from that employer so the family could live in a nicer white neighborhood.

“I’ve been blind,” Phelps said as he reflected on coming to see how his whiteness meant “there was a world that was available to me that wasn’t available to others.”

“I’m like the Buzz Lightyear in ‘Toy Story’ when he discovers that he’s not really Buzz Lightyear, he’s just a toy,” Phelps added.

Phelps, a graduate of Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, also said he did not even think for years about the fact that the founders of SBTS and the Southern Baptist Convention owned slaves. Nor, he added, did he think about that for 22 years as pastor of Highland Baptist Church in Louisville as the faces of slave owners James Boyce and Richard Furman looked back at him from stained glass windows as he preached.

“Now I see them,” Phelps added.

Phelps noted that while SBTS has “lamented” its slavery past, that is not enough since “lament is for your healing,” but “repair is for the healing of the victim.” He urged SBTS to repair the damage with reparations to a black school to “return some of the money that is soaked in slave blood, and be a witness.”

William Darity (Brian Kaylor/Word&Way)

Kevin Cosby, another SBTS graduate who serves as president of the historically-black Baptist school Simmons College of Kentucky, also spoke. He noted the importance of strengthening black institutions to empower the entire community with “self-determination.” Adding that “because the black community is a colonized community, we don’t control our economy, we don’t control our politics, we don’t control our schools.” To empower the black community, he sees the need for repair and reparations to undo the continuing generational impacts of slavery and Jim Crow.

Cosby mentioned the Bible’s two Hebrew words for “justice” to explain the need for repair and reparations: tzedakah and mishpat. Pointing to the story of Zacchaeus to explain the difference, he noted that Zacchaeus had “made his wealth as a collaborator with the Roman government, exploiting poor people.” But after meeting Jesus, Zacchaeus gave half his wealth to the poor since “he realized he had monopolized the wealth, and there were poor people because he had done injustice.” That act, Cosby explained, is mishpat justice that seeks to “create a more humane society where there’s equity and people have opportunity.”

“What many progressive, moderate, liberal Christians are often good at, when it comes to justice, is promoting the idea of mishpat, that there should be equity — and that’s right,” Cosby added. “But white America has a specific responsibility to help fix something that has been a crime against humanity for 400 years. And that is slavery for 246 years that stole trillions of dollars from black people. Plus another 100-plus years of semi-slavery of Jim Crow, sharecropping, convict-leasing. … And black people are suffering today because of this legacy.”

“This must be led by the Church,” he added. “It was the Church who led us in slavery and division. And the same Church must also lead us today for the next 400 years in justice and repair for people who have been damaged.”

The topic of reparations continued the next day during a workshop at the CBF general assembly. Commentators Yvette Carnell and Antonio Moore joined Duke University professor William Darity on a panel moderated by Cosby. The three made the case for governmental reparations. Darity, a leading expert on the topic, turned down an invite to testify in a U.S. House of Representatives hearing on reparations on June 19 so he could attend the Angela Project and CBF assembly.

“Racial justice requires reparations,” Darity said during the workshop. “Reparations is a moral imperative.”