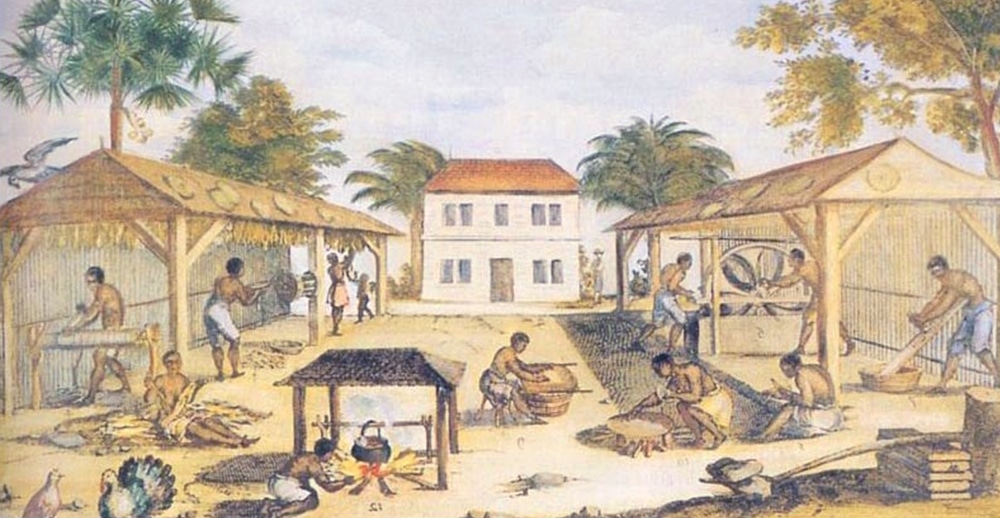

“Slaves working in 17th-century Virginia,” by an unknown artist, 1670. Image courtesy of Creative Commons

(RNS) — While Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell recently called human slavery America’s “original sin,” he dismissed calls for the federal government to pay financial reparations to descendants of slaves.

It has been 400 years since “20, odd Negroes” in chains arrived aboard the English ship “The White Lion” in Point Comfort, Virginia, in August 1619. A short time later, a second ship, “The Treasurer,” brought more Africans to be sold to the white Virginia settlers who had arrived in Jamestown a dozen years earlier.

Transporting Africans by ship across the Atlantic Ocean as slaves did not end until 1808, and scholars estimate about 455,000 Africans — including children — were brought to what became the United States. Besides being sold as property, the Africans were also stripped of their original names, languages, cultures and religions. Most slaves were forcibly converted to Christianity, their masters’ religion.

To break the spirits of slaves, their white owners used New Testament verses to justify human bondage:

- Slaves, obey your human masters with fear and trembling in the sincerity of your heart … (Ephesians 6:5)

- Slaves, obey your human masters in everything; don’t work only while being watched in order to please men, but work wholeheartedly fearing the Lord (Colossians 3:22)

- Slaves, submit yourselves to your masters with all respect, not only to the good and gentle masters, but also to the cruel ones (1 Peter 2:18)

- Slaves are to be submissive to their masters in everything, and to be well pleasing, not talking back (Titus 2:9)

Christian scholars, like the late David L. Bartlett of Yale Divinity School, have since reinterpreted such verses. “… We cannot take 1 Peter as a clear and infallible guide to contemporary faithful behavior,” Bartlett wrote in 1997. “Our understanding of slavery has changed.”

But long before Bartlett wrote such words, fearful white masters had little thought of changing their “understanding of slavery,” and armed with weaponized New Testament verses, masters frequently prohibited slaves from conducting their own Christian worship services. The slave owners feared religion could provide inspiration for a slave revolt.

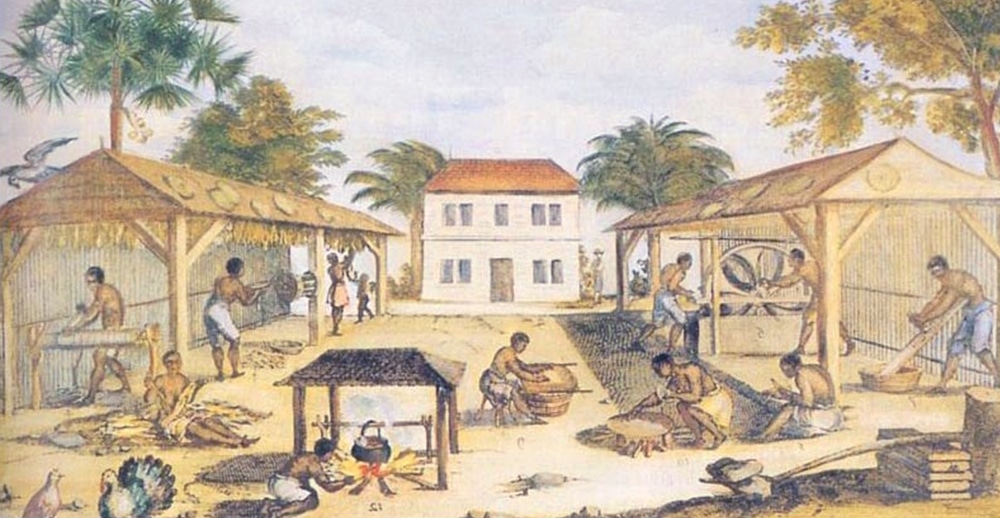

“Nat Turner and his confederates in conference” from an 1863 book. Image courtesy of Creative Commons

And they were right to worry. On Aug. 21, 1831, Nat Turner, a minister who knew the Bible, led a rebellion against white slave owners in Virginia. He spoke about “white spirits and black spirits engaged in battle … and the time was fast approaching when the first should be last and the last should be first.”

Turner’s uprising killed 55 white people and was quashed. But the slave insurrection frightened the white ruling class. Nine years earlier, President James Monroe, a Virginia slave owner, had helped establish Liberia in West Africa as an independent nation for the growing number of freed slaves in the United States. It is no accident that Liberia’s capital is named Monrovia.

But, of course, the human quest for liberation can never be fully extinguished. Turner may have failed with his rebellion, but African-American slaves used the teachings of the Hebrew Bible to sustain their spirit and hope during long years of human degradation.

Not surprisingly, they turned to the Exodus story of Hebrew slaves breaking free from Pharaoh’s cruel rule, leaving Egypt and wandering 40 years in the wilderness before triumphantly entering the Promised Land.

In a brilliant spiritual maneuver, the slaves in the American South, many of whom were forbidden to learn to read, heard their spiritual leaders, often women, orally relating the gripping story of Moses leading slaves to freedom.

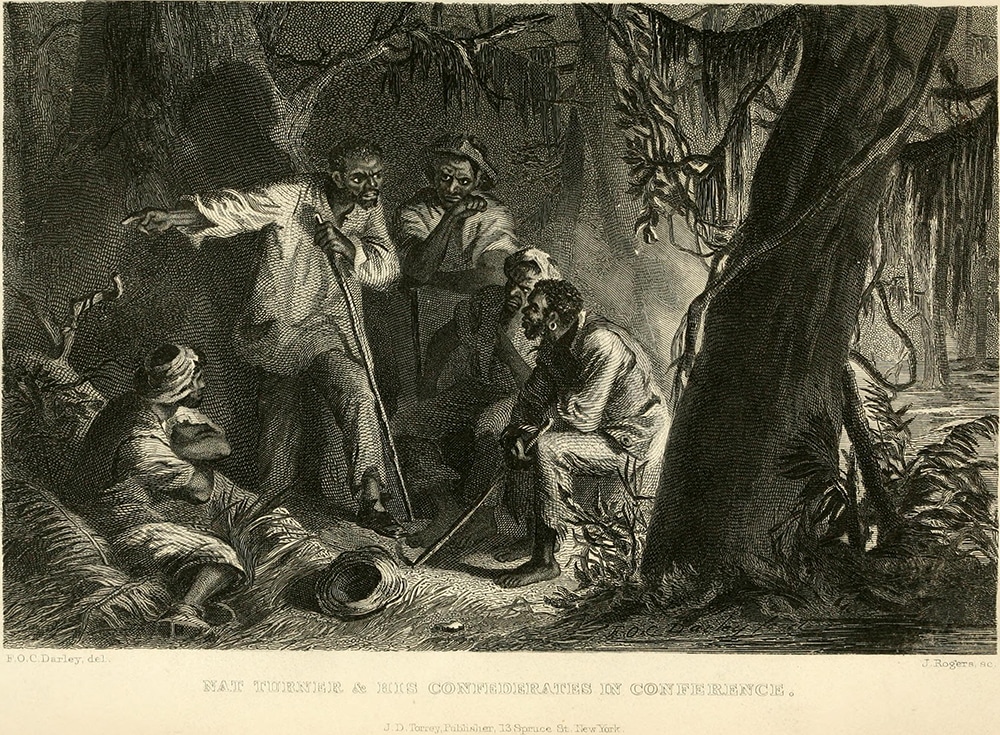

The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. speaks at an interfaith civil rights rally at the Cow Palace in San Francisco on June 30, 1964. Photo by George Conklin/Creative Commons

That biblical account presented a real and present danger to white slave masters. But they were unable to prevent the Exodus story from being used as the dream, the hope and the unstoppable force that drove slaves toward freedom.

No one employed the Exodus story with greater skill than the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. Many of his sermons frequently cited it, turning the slave owners’ religion of submission and subservience on its head.

This is one of the most significant developments in religious history. Passivity and servitude were cast aside and replaced with activism and the quest for human and spiritual liberation.

A bitter war was fought to rid America of the “peculiar institution” of slavery. Ironically, much of the major fighting in the Civil War took place in Virginia, the very region where the “original sin” took root in 1619.

Decades after the war, harsh discriminatory legislation was adopted, but those segregationist laws were opposed by brave men and women, black and white, who succeeded in legally overcoming “Jim Crow.”

As we approach the 400th anniversary of that fateful August day at Point Comfort, Americans, our political and religious leaders are charged by the sacred text to complete the arc begun by the slave masters, redirected by the slaves themselves and crystalized by King.

They would do well to remember the teaching of Yom Kippur, Judaism’s holiest day. A Talmud’s chapter on the Day of Atonement says:

“For the sins humans commit against God, the Eternal One will provide forgiveness. But for the sins humans commit against fellow humans, those sins must be atoned only by seeking out those we have harmed and making full repentance, full peace with the ones we have sinned against.”

But how does America achieve “full repentance” for the “original sin” of slavery?

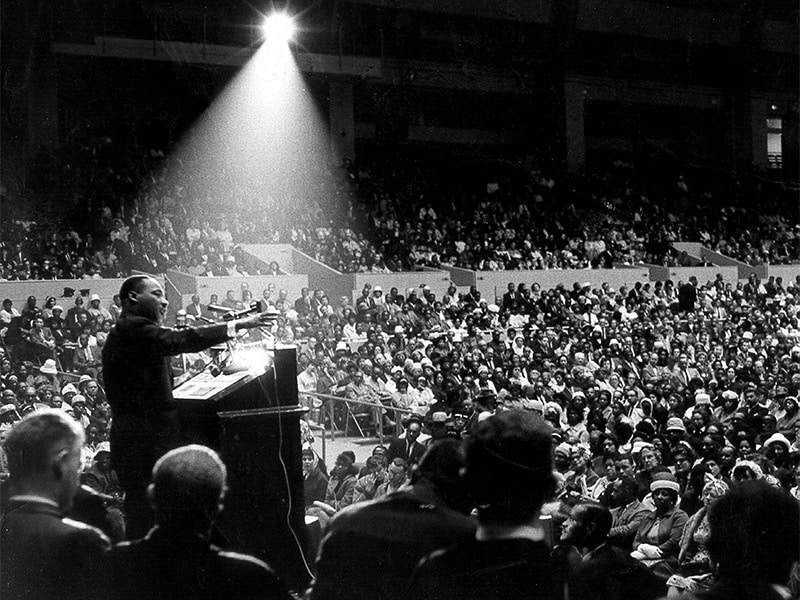

“A Ride for Liberty — The Fugitive Slaves” painting by Eastman Johnson circa 1862. Image courtesy of Brooklyn Museum/Creative Commons

That public debate is ongoing. Between 1989 and 2017, John Conyers, the former Democratic representative from Michigan, introduced legislation calling for the federal government to provide financial reparations to African Americans. His efforts were never enacted into law.

Today, the Emancipation Reparations Counter-Coalition works to compensate the descendants of the many African Americans who were members of the Union army during the Civil War. In June, the House Judiciary Committee held a hearing on a bill that would create a commission to study how to repair the damage done by slavery, the first time Congress has considered such a bill.

We may be moving toward a recognition of the sin of slavery in our history. The Charlottesville (Virginia) City Council, for instance, recently scrapped Thomas Jefferson’s birthday as a city holiday and replaced it with the date in 1865 when Union troops entered Charlottesville and ended slavery in Jefferson’s hometown.

But the nation has a long way to go before we accept the idea of reparations. Opponents see it as a “slippery slope” that will open the floodgates for other aggrieved groups in American society to demand reparations for perceived past discrimination. Critics claim it’s too late to provide reparations. They insist the emphasis must be on the future, not the past.

But after 400 years, America has begun moving toward its collective Day of Atonement in the national public square. Reparations arguments, pro and con, are likely to only intensify. As Bette Davis said in the famous film, “All About Eve,” “Fasten your seat belts, it’s going to be a bumpy night.”

“Slaves Waiting for Sale – Richmond, Virginia” painting by Eyre Crowe in 1861. Image courtesy of Creative Commons