Interpreter Valarie Holmes portrays Angela, one of the first enslaved Africans to arrive in Virginia, at Historic Jamestowne on March 30, 2019. RNS photo by Adelle M. Banks

JAMESTOWN, Va. (RNS) — Wearing a yellow headwrap, gray skirt and soiled apron, a woman who says she is “called by the name of Angela” stood by the James River and told her story, one of faith and courage, darkness and hope.

“Every day, I rise,” said interpreter Valarie Holmes in late March on her first day portraying an enslaved woman forcibly brought to Virginia 400 years ago. “And then I ask: ‘Great Spirit, speak to me and give order to my thoughts, my words, my hands, my feet this day.’”

A group of dozens of visitors to Historic Jamestowne, the preserved site of the first permanent English settlement in the U.S., listened on the windswept banks of the river as Holmes spoke, including snippets of faith in her story.

The presentation is just one of many ways Americans are commemorating the 400th anniversary of the arrival of “taken people,” as Holmes calls the first documented Africans who arrived against their will in Virginia.

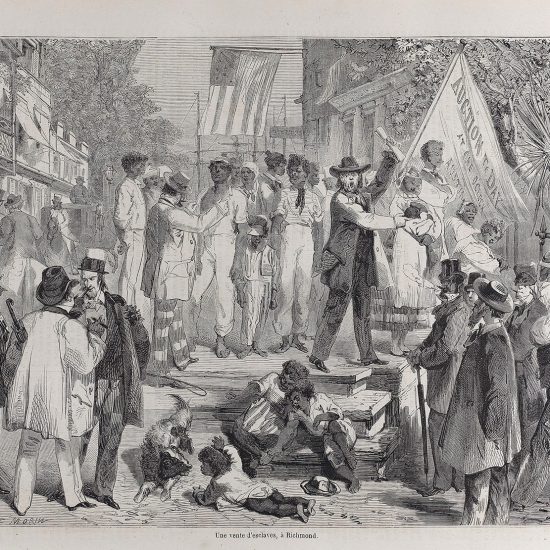

About 12.5 million Africans were transported and sold during the trans-Atlantic slave trade from the 16th to the 19th centuries. More than 300,000 were shipped to the U.S., historians estimate. The 1860 U.S. Census recorded a U.S. slave population of close to 4 million. The Emancipation Proclamation officially freed some Southern slaves in 1863 but many blacks remained enslaved until 1865.

Historic Jamestowne along the James River on March 30, 2019. RNS photo by Adelle M. Banks

Archaeologists continue to work to find out more about the places where Angela and other enslaved people were brought and details of the lives they led.

Holmes’ interpretation attempts to fill in the gaps even as she and scholars of this time in history say the specifics of Angela’s faith — and that of many other enslaved Africans brought to the U.S. — remain a mystery.

But experts say that she was nevertheless a believer of some sort.

“Angela, being someone who was taken from her homeland, having crossed oceans, being in a captive situation on strange land, displaced from everything that she knew — I would think, yes, she’s a woman of faith,” said Lauranett Lee, who moderated a recent scholarly conference titled “Faith Journeys in the Black Experience: 1619-2019” co-convened by Virginia Union University’s Samuel DeWitt Proctor School of Theology.

Holmes depicts Angela as a Catholic. Some 20 percent of African slaves were Muslim, historians estimate. Others practiced local, traditional religions.

“There’s going to be a mix because even those who arrived here were not specifically from the same area, the same tribe,” added Lee, a University of Richmond lecturer and the founding curator of African-American history at the Virginia Historical Society. “They were caught up in kidnapping and slave-trading nets and the slavers themselves did not want too many individuals from the same group to be together because then they could communicate.”

A copy of a 1625 list includes Angela, one of the first enslaved Africans to arrive in Virginia, at Historic Jamestowne on March 30, 2019. RNS photo by Adelle M. Banks

In Holmes’ 45-minute presentation, Angela spoke of Catholic priests who were among the “trespassers” in her homeland, the kingdom of Ndongo in what is now the west-central African country of Angola.

She said she was grabbed, gagged and marched some 100 miles to a pen in the Portuguese slave port of Luanda. Later, she was taken to a ship where she was chained to other captured Africans.

“All I kept hearing was ‘Bautista! Bautista’!” she said. “And I thought, John the Baptist! That cannot be good to go on a ship called John the Baptist!”

The ship, the San Juan Bautista, was attacked in the Gulf of Mexico before it reached its original destination on the Mexican coast.

About 60 Africans were robbed from the slave ship and transferred to two British pirate ships, according to Historic Jamestowne officials. The Treasurer, the ship that records show carried Angela, arrived a few days after the White Lion, in August 1619 in what is now known as Hampton, Va.

Holmes’ first-person account of Angela’s life followed a First Africans Tour led by public historian Mark Summers across the green grass and brick foundations on the property. He noted that the first General Assembly and the arrival of the first Africans occurred within weeks of each other four centuries ago.

Interpreter Valarie Holmes portrays Angela, one of the first enslaved Africans to arrive in Virginia, at Historic Jamestowne on March 30, 2019. RNS photo by Adelle M. Banks

During the tour, he passed out a 1625 document that lists Angela as “Angelo” and as “a Negro woman” in the household of Captain William Pierce.

“I think it’s a very spiritual thing to do, to recognize that you are where people were before, that something important happened there,” Summers said. “You get the point of view of people who didn’t always write down the story.”

The lack of a written story means interpreters have to use “a lot of deduction” to describe how they think Angela may have lived or believed, said Summers.

“I would argue if Angela’s name is Angela that tells us something: You have a Christian name,” he said in an interview about the name with “angel” at its root. “Now, is she already Christian or did the Portuguese convert her on the ship?”

Few priests questioned the validity of such conversions, said Summers. Bishops in Africa and beyond were noted by others for not condemning the slave trade.

“It would be very typical for the Catholic Portuguese to do mass conversions on the ships or at least attempt to baptize or convert,” Summers said. He noted that baptizers may have thought they were saving souls of the captives, many of whom would die in the Middle Passage as they traveled between Africa and the Americas.

Public historian Mark Summers, right, leads a First Africans Tour at Historic Jamestowne on March 30, 2019, in Jamestowne, Va. RNS photo by Adelle M. Banks

Another scholar of Jamestown’s history, Chardé Reid, said there is not enough information to pinpoint Angela’s faith.

“Everybody had their different spiritual beliefs that they held onto,” said the William and Mary graduate student, including Catholicism and Bakongo, a local religion that included ancestor veneration and is still practiced in Angola today, or a mixture of those faiths.

“I haven’t come across anything that describes her as being Christian or as holding a version of Bakongo religion.”

Dr. Lauranett Lee. Courtesy photo

Even as archaeologists continue to explore whether artifacts of Angela’s life might be hidden beneath the grounds of Historic Jamestowne, Lee, a Richmond-based public historian, said they may well be found beyond the material culture of books and house foundations.

Their history may show up, for instance, in vestiges of the “ring shout,” a worshipful dance used by slaves when they met in secret, or other religious expressions that contrast with traditional Anglican church practices “where you sit and you listen.”

“I think what’s more timely, relevant, essential to look at are the traditions that the people could hold onto and the ways that they expressed their faith,” she said. “And how that faith continues and evolves in this new landscape despite the adversity and the cruel lives that they had to endure.”