Art Simon, left, with Iva Carruthers at the “Silence Can Kill” book launch on June 10, 2019, at Capitol Hill Presbyterian Church in Washington, DC. Photo by Lacey Johnson for Bread for the World

(RNS) — Decades after former Lutheran pastor Art Simon founded the Christian advocacy group Bread for the World, he refuses to give up on the goal of ending hunger in the U.S. and across the globe.

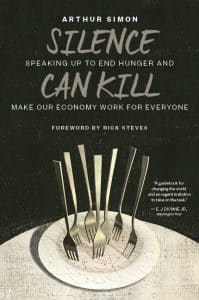

At 89, he has written a new book, “Silence Can Kill: Speaking Up to End Hunger and Make Our Economy Work for Everyone.” In it, he encourages readers — religious and nonreligious — to see the value in moving from solely charitable efforts to address hunger to also advocating for legislative action on the issue. He ends his book with practical steps for believers to take, from visiting poor neighborhoods and countries to get to know about the struggles of the people there to writing to members of Congress.

Simon, an ecumenical minister who is affiliated with the Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod, spoke to Religion News Service about the reluctance of some religious people to address hunger and why he thinks food banks are not sufficient to solve the hunger crisis.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

As founder of Bread for the World, you have long been concerned about hunger in this country and in the world. Is it any more likely that hunger can be ended in the near future than when you started your organization 45 years ago?

It’s much more likely. We’ve made tremendous progress in recent decades. But the last few years have actually set us back a little bit. So the goal of the U.N. Sustainable Development Goals, getting us to the end by 2030 — possible but a very steep hill. It will take some extraordinary efforts to make that happen by 2030.

What is it about your role as a faith leader that has led you to continue championing this cause?

It was my pastorate in New York City, in quite an economically poor neighborhood, that got me involved very directly in hunger and poverty issues. Before long I was involved in helping to put Bread for the World together as an idea and then, became the first president. I saw that as an extension of my pastoral ministry, actually, rather than a departure from it.

Art Simon at the “Silence Can Kill” book launch on June 10, 2019 at Capitol Hill Presbyterian Church in Washington, DC. Photo by Lacey Johnson for Bread for the World

What was it about that congregation where this became an issue for the people in the pews?

There were quite a number of people in the congregation who were economically poor. And the whole neighborhood context of the congregation — constantly dealing with people who were struggling to make a go of it and finding themselves running short on food, on money. And all sorts of complications that come along with hunger and poverty.

You note that religious people are often charitable, often running food banks or contributing to them, but that, that’s not enough. Why is that not enough?

Charity is a wonderful thing. Charity is essential and I’m still actively part of charitable efforts in hunger. But charity can only do so much. It’s quite limited in what it can do in the long run. It doesn’t have a sufficient spread to reach people who need the help and it doesn’t have the authority to make decisions for the nation as a whole. To end hunger — even to reduce hunger — we’ve got to get the whole nation behind it.

Only the government can speak for the nation as a whole. Second Harvest can do a lot, but it can’t do that.

“Silence Can Kill” by Art Simon. Courtesy image

You titled your book ‘Silence Can Kill.’ Why?

Because a lot of people are dying as a result of hunger. They’re dying because of hunger and poverty. That’s true especially globally when it’s very clear that large numbers of people who are extremely hungry and extremely poor simply die too soon. And, typically, the deaths occur mostly in infancy and in early childhood but it occurs in later years as well. But here in the States, it also takes a toll. Now, we don’t have lots of high death statistics to point to like we do in the case of global hunger. But here, too, people who are hungry, people who are poor, their lives are shortened.

Why do you think religious people are reluctant to act on this issue?

One of the reasons is that charity is what we are familiar with and comfortable with. That’s been in the biblical heritage from Old Testament times on all through the history of the church. We don’t do enough of it, but we do it and people understand that that’s part of what being a Christian involves. But advocacy involves something more complicated. It means engaging in leaders at the political level and people are not as comfortable with that because that can be controversial. Leadership in churches tend to back off from getting engaged in advocacy.

You write that when religious people do not speak up to politicians about hunger, that they are hurting their own faith. What do you mean by that?

Every Christian, I think in theory at least, believes that God calls us to be compassionate toward people who are hungry and poor. And that’s why charity seems OK. But if the answer to hunger and poverty requires responsible citizenship and changes in government policy, then it is the contradiction of our faith if we back away from engaging with hunger at that level.

What has been an example of success in the past when religious people have spoken to political leaders about hunger policy?

Bread for the World came up with the idea of getting legislation included in our foreign assistance to establish a child survival fund within our foreign aid program. Long story short, when the letters started coming in, members of Congress began to pay attention to it and they did establish a child survival fund in our foreign aid program. In combination with other efforts, hunger has been reduced worldwide because of child survival efforts. Not just Bread for the World’s. Our piece of it was one small piece, but an important piece. That’s just one case where a lot of people, largely people anchored in the church, got to their members of Congress and the consequence was millions of kids lived rather than died.

Art Simon signs copies of his book, “Silence Can Kill,” during the book launch on June 10, 2019 at Capitol Hill Presbyterian Church in Washington, DC. Photo by Lacey Johnson for Bread for the World

On the other side of this, what has been an example of a failure when people of faith have tried to get members of Congress or presidential administrations to do more?

We don’t like to broadcast too many of those (laughs) but I think back to the 1980s and the Reagan era when there was a pushback against safety net programs and so food stamps and other programs were cut back. Bread for the World and other advocacy groups were really pushed into a defensive mode to lobby against the cuts, but the cuts came. Probably not as extensive as they would have — I’m quite confident of that, in fact — but nevertheless, there was a setback.

How do you see this work to end hunger fitting into our current times when the country is so polarized?

The current crisis is really a setback to the hunger movement and to what we ought to be doing as a nation. But, having said that, it isn’t an entirely negative picture because Congress for the last couple of years, and going into the third year now, has with some minor exceptions stood up against President Trump in continuing the safety net programs and food stamps in particular and overseas development assistance and food assistance abroad. And I think a lot of that is due to the advocacy groups that have been bugging Congress over the years. They’re getting at least a partial hearing.

Hunger could become that morally anchored issue that is so decent and so good and so in tune with our national ideals and Christian ideals that it could become the issue that helped to crystallize an effort to change our economy in a more inclusive direction, an economy that would work for everybody and would include people now who are unemployed, underemployed, underpaid and ought to be given a better chance.

After all of this work that you’ve done for decades, even in this polarized time, you’re not giving up on the hope for the end of hunger?

Not giving up at all. I don’t think Bread is giving up or other advocacy groups are, or churches for that matter who are engaged this way. When there are setbacks you just got to work harder.

It’s not unreasonable. Sometimes it just takes reaching that tipping point in the public sense of things that hunger is an outrage in a country as wealthy as ours. If you think of England, back in the early 19th century and ending the slave trade and slavery — it happened because there were some dogged legislators like (William) Wilberforce and churches who began to help shape public attitudes on slavery.

Ultimately the nation as a whole decided slavery is something we’ve got to end.

I think something like that should happen with regard to hunger and extreme poverty here in the States.