Photo by Gift Habeshaw on Unsplash

After 15 years serving in Argentina as missionaries with the International Mission Board of the Southern Baptist Convention, Gary and Annetta Marie Snowden moved to Mexico for another IMB assignment. They expected to stay with the IMB until they retired. However, less than a year later they found themselves back in the United States with, as Gary put it, “no ministry position lined up, no house, no car, and a lot of question marks about our future.”

Like dozens of other IMB missionaries in 2002 and 2003, the Snowdens were forced out because they refused to sign the Baptist Faith & Message 2000, a confessional statement passed by the SBC two years earlier. But they weren’t the last to face such a demand, sparking the question: Can a confession become a creed.

In January 2002, then-IMB President Jerry Rankin wrote a letter to all IMB missionaries asking they sign the BF&M 2000. The next month, he said those who did not sign would not be fired or pressured to resign.

Yet, just 15 months later, in May 2003, the IMB’s trustees fired 13 missionaries who refused to sign the B&FM 2000. At that meeting, the trustees also accepted the resignations or early retirements of another 30 missionaries who refused to sign the document. Another 77 missionaries — including the Snowdens — were believed to have resigned or retired during the year prior, at least in part because of the signing demand. Thus, as many as 120 missionaries left due to the demand they viewed as un-Baptist.

“We regret on the one hand that we will be leaving missionary service,” Gary wrote in his resignation letter on July 11, 2002. “We are dismayed that the political infighting and controversy of the SBC during the past 20 years has now left its mark on the IMB. On the other hand, we leave with the full assurance that living in accordance with the dictates of our consciences (which we trust have been instructed and led by the Scriptures and the Holy Spirit) is more important than sacrificing our integrity in order to maintain a position with the IMB.”

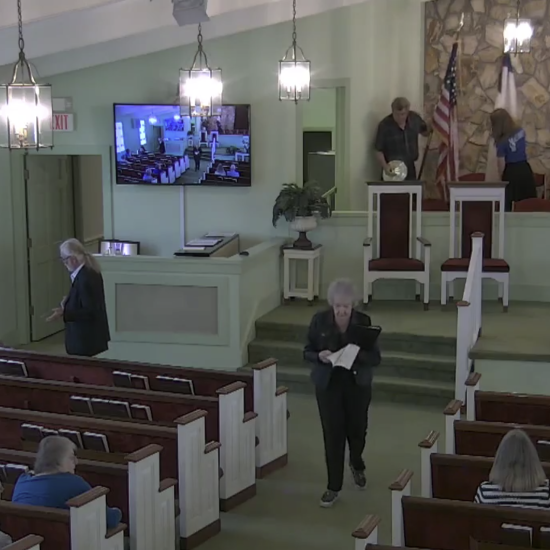

Gary Snowden preaching at Sexta Iglesia Bautista (Sixth Baptist Church) in Santiago de Cuba. (Brian Kaylor/Word&Way)

For Gary, the demand to sign the B&FM 2000 was inappropriate. He wrote in a previous letter to his IMB supervisor on April 3, 2002, that he found it troubling to see the move of SBC confessional statements “from being a consensus of generally held Baptist beliefs to an instrument of doctrinal accountability.”

“Baptists have historically resisted any creed apart from the Bible itself. Now, despite all the disclaimers to the contrary, that is exactly what the framers of the 2000 document have put in place. One can deny with all vehemence that the current BF&M is a creed, but its use as an instrument of doctrinal accountability clearly testifies to the fact that it has become such,” Snowden added.

“Individuals have no freedom or protection to exercise their freedom of conscience and express their differences in interpretation of scriptural passages from that set forth as authoritative and binding for all SBC employees in any agency whatsoever without risking loss of employment, or in the words of Rankin’s letter, being accused of heresy.”

The accusation of heresy particularly bothered Snowden, who graduated with a Ph.D. in church history from Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary in Fort Worth, Texas. He noted in his April 2002 letter that historically such a charge has only been “applied to those who denied the deity of Christ or the inspiration of the Scriptures of some equally fundamental Christian doctrine.” The BF&M, however, deals with many areas Snowden believed “do not even remotely approach those kind of basic beliefs.”

Snowden’s objections — like those given privately and publicly by many others during the debate over the new IMB rule — did not change Rankin’s demand. And in the years since then, many other Baptist institutions have demanded people sign the BF&M 2000 and other theological documents.

With this continuing push, the complaints of Snowden and others continue to echo: Is this a confession or a creed?

Creed Versus Confession

Roger Olson, professor of Christian theology and holder of the Foy Valentine Chair in Christian Ethics at George W. Truett Theological Seminary in Waco, Texas, offers a narrow definition of what counts as a creed and how this differs from a confession of faith.

Olson tends to use the term “creed” only to refer “an expression of what is essential for being ‘Christian’ in terms of doctrine.” And he uses the label “confession of faith” for “a denomination’s particular statement of its own distinctives in addition to the creed.” Olson admitted that many use the term “creed” to describe “any binding statement of faith.” But, he added, he still calls those “confessions of faith.”

“I make a distinction between confessions that are binding and those that are not. For example, if one is ordained in the Christian Reformed Church, he or she must pledge allegiance to three ‘symbols of unity’ — the Heidelberg Catechism, the Belgic Confession, and the Canons of the Synod of Dort,” Olson explained. “Many Baptists, on the other hand, use the Baptist Faith & Message (1963 or 2000) as a confessional statement expressing the consensus of the denomination, association, or congregation (but not requiring ordinants to pledge allegiance to it).”

For Olson, there “is really only one Christian creed — the Nicene Creed of Constantinople” adopted in 381 A.D. He noted that some will name three creeds, but he sees the Apostles Creed as “actually just an abbreviation of the Nicene Creed,” and the Athanasian Creed as “an expansion of the Nicene Creed.” Regardless of whether one prefers to count those documents as one creed or three creeds, he distinguishes such a creed from a confessional statement, binding or otherwise. That definition of creed aligns with Snowden’s view that the charge of heresy historically was saved for those denying essential Christian beliefs — like those found in the Nicene Creed.

Yet, Olson sees a danger in using a confessional statement in a creedal manner, such as when organizations “require people to sign a confessional statement and treat it as an instrument of doctrinal accountability and especially when they treat it as equally authoritative with the Bible and as a set of doctrines all Christians must believe.”

“Creeds and confessional statements treated in a creedal manner can become equal in authority with Scripture and make it impossible for Scripture to reform the church,” he added.

Meredith Stone, associate dean for academics at Logsdon Seminary and assistant professor of Scripture & ministry at Hardin-Simmons University in Abilene, Texas, similarly sees the danger of attempting to treat a confession like a creed.

“There is a fine line between creeds and confessions. While creeds are intended to state the essential beliefs of a certain religious group to which adherents must conform, confessions are intended to be a statement of general consensus of a religious group,” she said. “In this way, creeds are more prescriptive, meaning they tell people what they must believe, and confessions are more descriptive, they state those beliefs on which people generally agree.”

“The fine line begins to be crossed when a confessional group asks those within its ranks to conform to the statements in the confession, when it moves from descriptive to prescriptive,” she added. “Baptists, who are a confessional group, also hold high the autonomy of the local church, meaning that the local church has the right to decide how it will interpret scripture, appoint/ call leadership, and govern its affairs. If confessional people begin moving toward creedalism, the value of the autonomy of the local church is jeopardized.”

The Push Continues

In November 2018, Southwest Baptist University in Bolivar, Missouri, fired professor Clint Bass for violating the faculty handbook after he met with Missouri Baptist Convention leaders and others in an alleged effort to push out other members of SBU’s Redford College of Theology and Ministry. As he unsuccessfully appealed his dismissal, he and his supporters claimed some of the other Redford professors did not adhere to the BF&M 2000. Additionally, six of the eight Redford professors were criticized for attending Baptist churches that have not officially adopted the BF&M 2000. Yet, five of those professors criticized were members at First Baptist Church in Bolivar, which has adopted the BF&M 1963.

Bass and his supporters appear to conflate the terms “creed” and “confession.” For instance, a December 2018 document detailing Bass’s allegations against his former colleagues attacks Redford professors for rejecting attempts to implement the BF&M 2000 as a binding creedal statement. For rejecting such creedalism, the document calls the professors “anti-confessionalism.” But does rejecting the use of a confession as a creed mean rejecting confessions as confessions?

The first version of the SBC’s BF&M came in 1925, though it was largely based on an earlier Baptist confessional statement, the 1833 New Hampshire Confession of Faith. The 1925 effort was led by E. Y. Mullins, a prominent Baptist who served as SBC president, Baptist World Alliance president, and led Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Kentucky, for nearly 30 years. Sanford Brown, a founding co-editor of Word&Way, also served on the drafting committee. The confessional statement came amid debates in the 1920s over modernism and Fundamentalism, and it was credited with preventing a major split in the SBC.

That statement’s introduction noted that such confessions “constitute a consensus of opinion of some Baptist body” but are not “complete statements of our faith” and do not have “any quality of finality or infallibility.” Additionally, it argued that “the sole authority for faith and practice among Baptists is the Scriptures of the Old and New Testaments” since “confessions are only guides in interpretation, having no authority over the conscience.”

In 1963, SBC messengers approved a new version of the BF&M amid controversy about a book on Genesis by Ralph Elliot, then a professor at Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary in Kansas City, Missouri — and the new BF&M was approved by messengers during the SBC’s annual meeting in Kansas City. Although based on the 1925 version, it offered an expanded take on general Southern Baptist beliefs. Then-SBC President Herschel Hobbs, who served as pastor at First Baptist Church in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, and was well-known for his preaching on The Baptist Hour national radio show, led the rewrite effort. After his death, his church left the SBC in 2001 as a result of the 2000 BF&M. Like the 1925 version, the 1963 BF&M insisted it was not to be a binding document.

“Such statements have never been regarded as complete, infallible statements of faith, nor as official creeds carrying mandatory authority,” the 1963 BF&M’s introduction explains. “The sole authority for faith and practice among Baptists is Jesus Christ whose will is revealed in the Holy Scriptures.”

The 2000 version came after then-SBC President Paige Patterson appointed a committee, led by Adrian Rogers, to update the document after the rightward shift of the SBC as a result of the movement Patterson led along with Paul Pressler. (Patterson was fired last year by SWBTS trustees for mishandling allegations of rape, and multiple men have accused Pressler in court filings of unwanted sexual advances.)

The 2000 document included what many Baptist theologians and pastors viewed as significant changes from the earlier versions, including more Calvinist language and statements limiting the roles of women. The 2000 document was also criticized for confusing confessionalism with creedalism. For instance, an introduction to the BF&M 2000 said Baptists “have adopted confessions of faith as a witness to the world, and as instruments of doctrinal accountability.” It did say, however, that Baptists “deny the right of any secular or religious authority to impose a confession of faith upon a church or body of churches.”

Despite the claim that such a confession could not be imposed, many in Southern Baptist life have — like the IMB — used the BF&M 2000 to demand what they believe is “doctrinal accountability.” In fact, many Baptist institutions require the signing of a confessional document — or, increasingly, to affirm multiple statements.

Two professors at Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary resigned in 2001 instead of signing a statement affirming the BF&M 2000. They had previously affirmed their support of the 1963 version, but could not support the changes in the document. Other Southern Baptist seminaries similarly require the signing of statements.

Professors at Southern Baptist Theological Seminary must publicly sign the Abstract of Principles, a confessional statement written in 1858 by Basil Manly Jr., one of SBTS’s founding faculty members. At the time, Manly was a slaveholder who preached the Bible justified slavery. Despite that, Mohler continues to insist Manly and the other slaveholding founders showed “courageous affirmation of biblical orthodoxy.”

Application of the Abstract at SBTS changed in recent years. While professors used to be able to sign the document while holding an interpretation of the document at odds with others, Mohler now demands they affirm their belief in the document — as he interprets it — when signing it, even though the statement affirms as one of its 20 statements the “liberty of conscience.”

The year after he assumed the presidency, he pushed out Molly Marshall as a professor because he believed she taught outside the Abstract, a charge she denied. Marshall, now president of Central Baptist Theological Seminary in Shawnee, Kansas, argued at the time that Mohler did not have the right to alone interpret the Abstract and that interpretation “has always been left to the liberty of the conscience of the faculty member.”

Professors at Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary in Wake Forest, North Carolina, must sign the BF&M 2000 and the Abstract of Principles. And since 2004, they must also affirm the Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy, and the Danvers Statement on Biblical Manhood and Womanhood. In the public ceremonies when a new SEBTS professor signs the documents, the provost holds up the Abstract of Principles and the BF&M 2000 while declaring, “Here we stand! This we believe! This we defend!”

New faculty at Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary must sign the seminary’s Articles of Faith, and while doing so also publicly declare their affirmation of the BF&M 2000, the Chicago Statement, and the Danvers Statement.

Other institutions take a different approach. For instance, Eastern University, a school in St. Davids, Pennsylvania, affiliated with American Baptist Churches USA, must sign a doctrinal statement that, with the exception of a sentence about believer’s baptism, is closer to Olson’s definition of a creed than a denominational confession. And even then, non-Baptist professors and leaders at the school are exempted from subscribing to the sentence about baptism.

Moving Forward

While the Bass controversy was ongoing at SBU, the MBC demanded that its six institutions adopt the BF&M 2000 as the official theological statement of their institution. While five institutions have done so, SBU has not. MBC messengers in October gave SBU trustees an extension for implementing that and other governance demands. There have been implicit threats of possible legal action against SBU if they do not meet the MBC’s demands.

The MBC now also requires any church desiring to affiliate to officially adopt the BF&M 2000, though existing churches have thus far been grandfathered in from that policy.

While the BF&M 2000 doesn’t address litigation among believers like Paul did in 1 Corinthians 6, it does reject the notion of a convention imposing authority over others.

“Christ’s people should, as occasion requires, organize such associations and conventions as may best secure cooperation for the great objects of the Kingdom of God,” all three versions of the BF&M state. “Such organizations have no authority over one another or over the churches.”

“In Christian education there should be a proper balance between academic freedom and academic responsibility,” the 1963 and 2000 versions add. “The freedom of a teacher in a Christian school, college, or seminary is limited by the pre-eminence of Jesus Christ, by the authoritative nature of the Scriptures, and by the distinct purpose for which the school exists.”

Still, the fights over the BF&M 2000 continue nearly two decades after its passage. And more than 17 years after leaving the IMB over the demand to sign the BF&M 2000, Gary Snowden said he didn’t regret his decision. Although he admitted “it was extremely painful at the time,” he explained that “it was too important of a matter of principle and conscience to do otherwise.”

“I emailed former missionary colleagues in Argentina as well as our mission family in Mexico City, explaining our decision to resign, and received tremendous support back from them,” he added. “Several indicated that had they not been so close to retirement, they would have done likewise.

Since then, Snowden has served as associate minister at First Baptist Church in Lee’s Summit, Missouri, and as the mission team leader for Churchnet. He noted that these roles have allowed him “to continue to channel my passion for missions into our ongoing partnerships with Baptists in Guatemala and Cuba.”

And today he also hopes that Baptists return to a historic understanding of the best uses of confessions of faith.

“I would hope and pray that Baptists would learn once again to honor and respect the historic principle of the priesthood of the believer and the right of every Christian to interpret the scriptures for themselves,” he explained. “I would also hope that Baptists could recover a bit of humility when it comes to holding a conviction about what they believe the Bible teaches — recognizing that their own interpretations of it aren’t infallible.