People line up for a human chain around the Jewish synagogue and the cemetery during the Sabbath celebrations in Halle, Germany. A heavily armed assailant ranting about Jews tried to force his way into a synagogue in Germany on Yom Kippur, Judaism’s holiest day, then shot two people to death nearby in an attack that was livestreamed on a popular gaming site in October. (AP Photo/Jens Meyer, File)

On Dec. 1, a band of assailants opened fire on worshippers at a small-town Protestant church in Burkina Faso, an impoverished West African country where the Christian minority is increasingly a target of attacks. The victims included the pastor and several teenage boys; regional authorities attributed the attack to “unidentified armed men” who, according to witnesses, got away on motorcycles.

The slaughter merited brief reports by international news outlets, then quickly faded from the spotlight — not surprising in a year where attacks on places of worship occurred with relentless frequency. Hundreds of worshippers and many clergy were killed at churches, mosques, synagogues and temples.

A two-week span in January illustrated the scope of this somber phenomenon. In Thailand, a group of separatist insurgents attacked a Buddhist temple, killing the abbot and one of his fellow monks. In the Philippines, two suicide attackers detonated bombs during a Mass in a Roman Catholic cathedral on the largely Muslim island of Jolo, killing 23 and wounding about 100. Three days later, an attacker hurled a grenade into a mosque in a nearby city, killing two Muslim religion teachers.

The worst was yet to come.

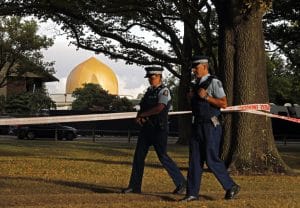

Police officers patrol at a park outside the Al Noor mosque in Christchurch, New Zealand. On March 15, 2019, a gunman allegedly fueled by anti-Muslim hatred attacked two mosques in Christchurch, killing 51 people. (AP Photo/Vincent Yu, File)

On March 15, a gunman allegedly fueled by anti-Muslim hatred attacked two mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand, killing 51 people. The man arrested for the killings had earlier published a manifesto espousing a white supremacist philosophy and detailing his plans to attack the mosques.

At a national remembrance service two weeks later, Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern said New Zealanders had learned the stories of those impacted by the attacks — many of them recently arrived immigrants.

“They were stories of those who were born here, grew up here, or who had made New Zealand their home. Who had sought refuge or sought a better life for themselves or their families,” she said. “They will remain with us forever. They are us.”

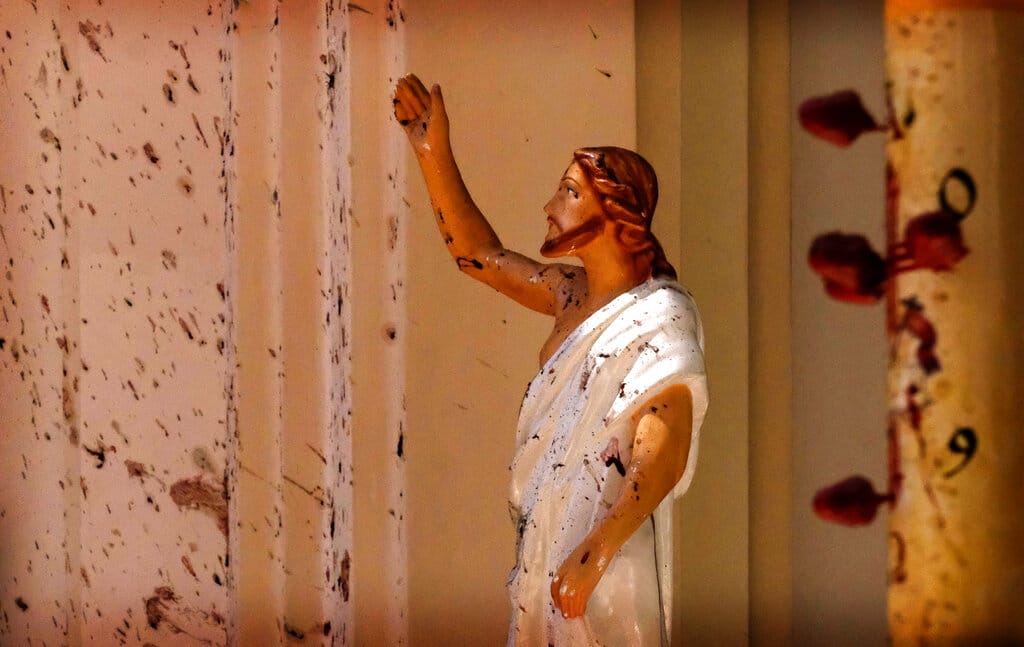

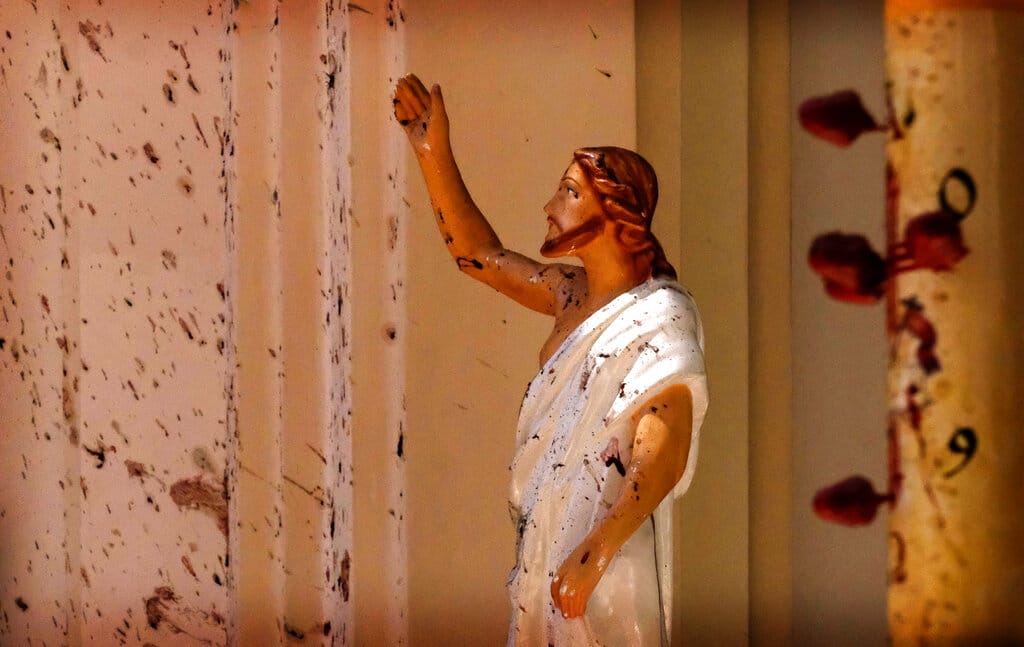

Sri Lankan Navy soldiers stand guard in front of the St. Anthony’s Shrine in Colombo, Sri Lanka. On Easter Sunday, April 21, bombs shattered the celebratory services at two Catholic churches and a Protestant church in Sri Lanka. (AP Photo/Eranga Jayawardena)

On Easter Sunday — April 21 — bombs shattered the celebratory services at two Catholic churches and a Protestant church in Sri Lanka.

Other targets, in coordinated suicide attacks by local militants, included three luxury hotels. But Christian worshippers at the three churches — including dozens of children — accounted for a large majority of the roughly 260 people killed.

The victims at St. Anthony’s Shrine in Colombo included 11-month-old Avon Gomez, his two older brothers and his parents.

The day’s biggest death toll — more than 100 — was at St. Sebastian’s, a Catholic church in the seaside town of Negombo. It’s known as “Little Rome” due to its abundance of churches and its role as the hub of Sri Lanka’s small Catholic community.

Blood stains a Jesus Christ statue at the St. Sebastian’s Church after a blast in Negombo, north of Colombo, Sri Lanka. On Easter Sunday, April 21, bombs shattered the celebratory services at two Catholic churches and a Protestant church in Sri Lanka. (AP Photo/File)

The attacks surprised many in the predominantly Buddhist country, where the Christian community totals about 7% of the population and has long avoided involvement in bitter ethnic and religious divides.

Six days after Easter, more than 9,400 miles (15,000 kilometers) from Sri Lanka, a gunman opened fire inside a synagogue in Poway, California, as worshippers celebrated the last day of Passover. A 60-year-old woman was killed; an 8-year-old girl and two men, including the Chabad of Poway’s rabbi, were wounded.

Some congregation members said the slain woman, Lori Kaye, blocked the shooter by jumping in front of rabbi Yisroel Goldstein, whose two index fingers were injured.

The man charged with murder and attempted murder in the attack, John T. Earnest, could face the death penalty if he is convicted of murder, although prosecutors haven’t yet said whether they will pursue capital punishment.

A couple embrace near a growing memorial across the street from the Chabad of Poway synagogue in Poway, Calif. A 19-year-old gunman opened fire as about 100 people were worshipping exactly six months after a mass shooting in a Pittsburgh synagogue, killing one and injuring more. (AP Photo/Greg Bull, File)

At a court hearing in September, prosecutors played a 12-minute recording of Earnest calmly telling a 911 dispatcher that he had just shot up a synagogue to save white people from Jews.

The attack occurred exactly six months after 11 people were killed at a Pittsburgh synagogue in the deadliest assault on Jews in U.S. history.

An additional anti-Semitic bloodbath was narrowly averted in October when an armed assailant tried to blast his way into a synagogue in Halle, Germany, where scores of worshippers were attending services on Yom Kippur, the holiest day in Judaism.

Unable to break through a locked door, the gunman went on a rampage in nearby streets, killing two people and wounding two others.

Authorities said the 27-year-old German man who has confessed to the attack had posted an anti-Semitic screed before the assault and broadcast the shooting live on a popular video game site.

In contrast to the Poway and Halle attacks, where authorities have identified suspects and motives, some of the worst attacks on houses of worship unfold without arrests or claims of responsibility.

In October, for example, more than 60 people were killed in a bombing during Friday prayers at a mosque in the village of Jodari in eastern Afghanistan.

No group claimed responsibility and authorities offered conflicting explanations of how the bombing was carried out.

One common element of all the attacks: Dismay that many people of faith now have reason for apprehension as they gather for worship.

“No one should have to fear going to their place of worship,” said California Gov. Gavin Newsom after the Poway attack. “No one should be targeted for practicing the tenets of their faith.”

Relatives place flowers after the burial of three victims of the same family, who died in an Easter Sunday bomb blast at St. Sebastian Church, in Negombo, Sri Lanka. On Easter Sunday, April 21, bombs shattered the celebratory services at two Catholic churches and a Protestant church in Sri Lanka. (AP Photo/Gemunu Amarasinghe, File)