Photo by Thomas Kelley on Unsplash

(The Conversation) Over the centuries, theologians have wrestled with many knotty questions, such as: Does God exist? What is the purpose of life? And why do innocent people suffer?

A layperson might suppose theology, the study of God, to be so serious that theologians never crack a smile.

The mention of Franz Bibfeldt, however, can melt even the iciest solemnity among not only theologians, but also clergy, students of religion, and even atheists. As one reviewer wrote, “The world needs a little more Bibfeldt.”

The authorized story

It was many years ago while studying at the University of Chicago Divinity School that I first encountered the name Franz Bibfeldt, along with two widely divergent accounts of his life and career.

The first and rather dubious biography, composed by some playful scholars and marinated in mirth, holds that Bibfeldt was born in Sage-Haast bei Groszenkneten in Germany in 1897. It states that as a young man, Bibfeldt stumbled upon his first original insight when he began to study the early Christian church.

At the time of Christ’s birth, Bibfeldt allegedly asked, how did the Romans manage to shift from counting down the years – 100 B.C., 50 B.C., 10 B.C. – to counting upward – A.D. 10, A.D. 50, A.D. 100 – especially since they never interposed a year 0?

His biographers go on to allege that Bibfeldt mined this discovery in his dissertation, “The Problem of the Year Zero.”

Bibfeldt’s subsequent work was wide-ranging, his biographers explain, noting his response to the great Danish theologian Soren Kierkegaard.

In his masterpiece “Either/Or,” Kierkegaard contrasts two sharply opposed approaches to life, the pleasure-focused and the responsibility-focused. Opting for a more inclusive approach, Bibfeldt is said to have responded with a work entitled, “Both/And,” in which he promoted a combination of both approaches.

When this work met with criticism, Bibfeldt, his biographers note, produced a sequel that received appropriately mixed reviews, “Either/Or and/or Both/And.”

The name Bibfeldt has become associated with the theology of Both/And, which denies nothing to anyone. The theologian’s mission, Bibfeldt seems to suggest, is to reconcile everything to everything.

Some have claimed that Bibfeldt even managed to reconcile life and death. His most groundbreaking work is said to give voice to perhaps that most oppressed of all groups – the dead. In one paper on the topic, Bibfeldt is noted to have highlighted the “ennui, the awful day-in-day-out life of the dead.” He is said to have drawn attention to the high rates of depression of the dead attending their “sedentary lifestyles” and the fact they were denied “any meaningful work and sense of accomplishment.”

At this point, many readers might be asking, was Bibfeldt for real?

The unauthorized story

Not exactly.

There is a second, better-documented account of Bibfeldt’s origin and inspiration.

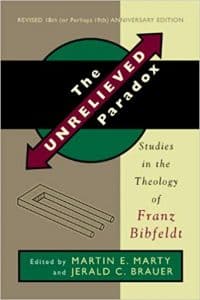

Editors Martin E. Marty and Jerald C. Brauer examined Franz Bibfeldt’s famously flexible theology in The Unrelieved Paradox.

In this version, which began unfolding in the 1940s, Bibfeldt first appeared when a student at Concordia Seminary, Robert Clausen, found himself locked out of the school library the weekend before his term paper was due. Unable to access the texts he intended to cite, Clausen instead decided to rely on his imagination and made them up. One such theological source was Franz Bibfeldt.

As the story goes, Clausen and a classmate, Martin Marty, now an emeritus faculty member at the University of Chicago, spent the next three summers working as manual laborers and embellishing the Bibfeldt legend. Marty published a 1951 review of Bibfeldt’s book, “The Relieved Paradox,” in the Concordia Seminarian.

Many professors, bookstores and publishers were soon in on the joke. But not everyone was amused.

When some of Bibfeldt’s features were deemed to bear too close a resemblance to members of Concordia’s faculty, Marty lost his fellowship to study overseas and was instead assigned to a congregation whose job requirements included graduate study at Chicago.

For this reason, to this day Marty cites Bibfeldt as “the theologian who had the greatest influence on my work.” He also praises Bibfeldt as a powerful reminder that “a person need not exist in order to influence lives.” Marty should know, because he has been one of the most important contributors to the Bibfeldt legacy.

Bibfeldt’s legacy

In one sense Bibfeldt is unreal, perhaps even a hoax, though he is the product of no malicious intent. And yet, in another sense, he lives on.

One of the sketches of Franz Bibfeldt receiving an honorary degree. The University of Chicago Magazine Feb 1995

Today the University of Chicago is the world center for Bibfeldt studies. It has established not an endowed chair in his name but a stool, which produces an annual stipend of US$29.95 for the person who delivers the annual Bibfeldt lecture – provided he or she can come up with a nickel in change.

In a Feb. 1995 issue of the University of Chicago Magazine, some graduate students even sketched images of Bibfeldt. As the magazine states, these students depicted the theologian receiving “an honorary degree from Twaddle Community College, catching a Sox game, and suffering delusions of grandeur.”

Some might see in Bibfeldt’s satirical origins a failure to take God seriously enough. But the dozens of theologians who have spoken and written on him see another lesson – the imperative not to take ourselves too seriously. Bibfeldt, his creators contend, stands for being everything to everyone. His example serves as a reminder that life challenges each of us to become someone and to help others do the same.

His story doesn’t just tell us what to think; instead it challenges each of us to think for ourselves.

The Conversation is an independent and nonprofit source of news, analysis and commentary from academic experts. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.