Attendees participate in a worship service during the Mosaix Global Network’s Multiethnic Church Conference on Nov. 5, 2019, in Keller, Texas. RNS photo by Adelle M. Banks

KELLER, Texas (RNS) — For four hours at a megachurch outside of Dallas, pastors of color shared their personal stories of leading a multiethnic church.

One, a lead pastor of a Southern Baptist congregation in Salt Lake City, recalled the “honest conversations” he had with his 10-member leadership team before it agreed that he would present “both sides” of the controversy over quarterback Colin Kaepernick’s kneeling protests at NFL games.

A founding elder of a fledgling Cincinnati congregation expressed satisfaction with her “phenomenal church,” but said “Lift Every Voice and Sing” — a hymn often called the “black national anthem” that most African American churchgoers learn in childhood — is so rarely featured at her multiethnic church that her younger daughter learned it instead from Beyonce‘s version.

A pastor of a church in Atlanta adapted his multicultural services so that its prayers, food, and sermon illustrations included not only traditions of blacks and whites but those of a member from India, who had noted that his culture had not been acknowledged.

Those leaders, who met at Mosaix Global Network’s Multiethnic Church Conference in November, are part of a decades-long, still burgeoning movement to integrate Christian worship services, aiming to refute the oft-quoted saying by the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. that Sunday mornings are the most segregated time of the week in the United States.

In 1998, 6% of congregations of all faiths in the U.S. could be described as multiracial; in 2019, according to preliminary findings, 16% met that definition. In that time frame, mainline Protestant multiracial congregations rose from 1% to 11%; their Catholic counterparts rose from 17% to 24%; and evangelical Protestant multiracial congregations rose from 7% to 23%.

Michael Emerson, a professor of sociology at the University of Illinois at Chicago and co-author of “Divided by Faith: Evangelical Religion and the Problem of Race in America,” said recent research seems to indicate that multiethnic congregations are continuing to sprout up at an “impressive” rate. “They’re growing faster than I would have thought,” said Emerson in an interview about his ongoing work with scholars at Baylor and Duke universities.

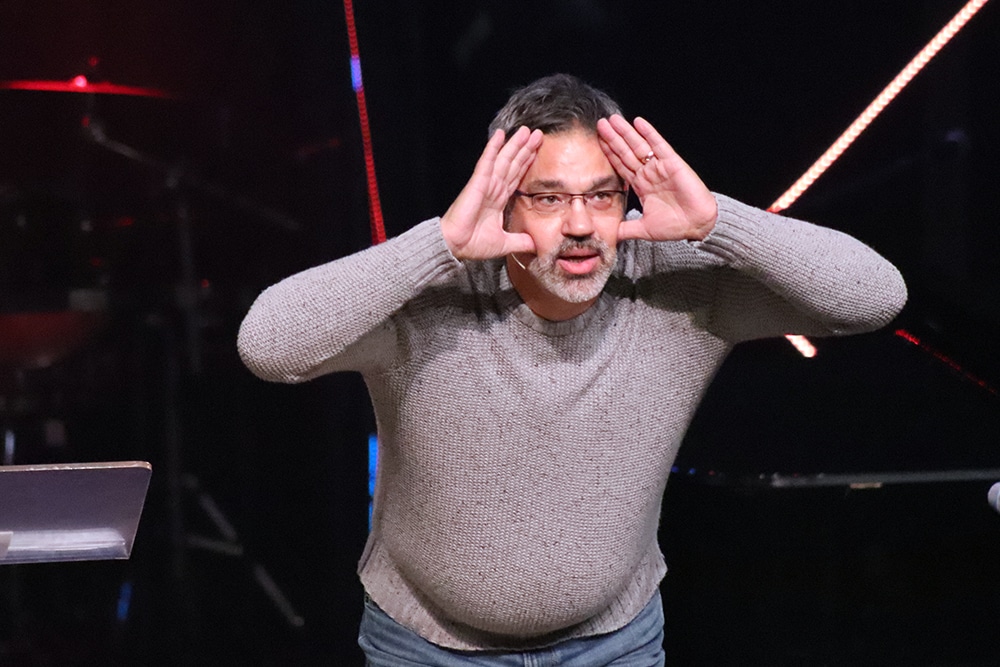

Michael Emerson speaks during the Mosaix conference on Nov. 6, 2019, in Keller, Texas. RNS photo by Adelle M. Banks

The rapid growth can sometimes obscure the fact that life in a multiracial church isn’t always easy. Mosaix co-founder Mark DeYmaz said the discussions at the conference, which now brings together more than 1,300 pastors, denominational leaders and researchers every three years, always demonstrate to him the contradictory reality of trying to unite black, white and other church traditions under one roof.

“The way you get comfortable in a healthy multiethnic church is to realize that you go, ‘Man, I’m uncomfortable here,’” he said in an interview in early January.

“We embrace the tension and that’s very different than the normative church, which is trying to make everybody comfortable,” said DeYmaz.

A white former youth pastor, DeYmaz founded Mosaic Church, a multiethnic, nondenominational congregation in Little Rock, Arkansas, in 2001, after he grew bothered that the only people of color at the church where he had long served were janitors.

He said he determined through biblical study that “the New Testament church was multiethnic.”

In 2004, he joined with like-minded colleagues to start Mosaix Global Network, which draws an array of racially and ethnically diverse mainline, evangelical and nondenominational Protestants.

(At many Catholic parishes, diversity is a given — nearly all of the growth in the U.S. Catholic Church in recent years has been driven by immigration into existing parishes. The question Catholic clergy and communities often face is not whether to establish a multiethnic church, but how to respond to the diverse needs of their parish.)

Co-founder Mark DeYmaz speaks at the Mosaix Global Network’s Multiethnic Church Conference on Nov. 5, 2019, in Keller, Texas. RNS photo by Adelle M. Banks

DeYmaz attributes the growth of multiracial churches in part to some clergy of color no longer wanting to lead homogenous congregations. Instead, they start multiethnic ones.

“More and more, people of color, they’re not going to allow themselves to be siloed,” he said.

Emerson said the preliminary results show that black clergy heading up multiracial churches have increased from 4% to 18% from 1998 to 2019. The number of Hispanics with their own church has risen from 3% to 7% in that time, with Asian Americans increasing from 3% to 4%. Whites leading multiethnic churches, meanwhile, have decreased from 87% to 70%.

Emerson said the increasing role of African American leaders is “an important trend” and agrees much of it is driven by black pastors starting churches with the goal of them being racially diverse.

Difficult for any clergy person, leading a multiracial church is especially daunting for clergy of color.

Korie Edwards speaks during the Mosaix conference on Nov. 6, 2019, in Keller, Texas. RNS photo by Adelle M. Banks

Korie Edwards, an Ohio State University associate professor of sociology, calls these pastors “estranged pioneers.” The principal investigator of the Religious Leadership and Diversity Project, Edwards collected information from 121 head clergy of Catholic, mainline Protestant and conservative Protestant churches of all sizes through in-depth interviews by her team of nine researchers.

She has discovered that pastors of color find they are often valued neither by their home churches predominated by their own racial/ethnic group nor by whites in the multiethnic churches they now lead.

“You’re first dismissed and then you are dissed. You’re not included in white circles as peers or you’re not included in white circles as a leader; you’re not respected as a leader,” Edwards said in a workshop she led at November’s Mosaix conference. “In these interviews, people have talked about depression, they’ve talked about nervous breakdowns, they’ve talked about how difficult and how painful it is.”

Edwards cited one African American pastor of a multiethnic United Methodist church on the West Coast who said he wondered at times if a problem he faced was racism or ignorance. An Asian American pastor who planted a multiracial Southern Baptist church in the Northeast described his trepidation about discussing the killing of Michael Brown, an unarmed young black man, by a white police officer in Ferguson, Missouri.

A recent Faith, Race & Politics conference convened by Johns Hopkins University’s SNF Agora Institute gathered faith, community and thought leaders in Cincinnati to learn from the experience of a local multisite megachurch that is about 82% white. Chuck Mingo, the black pastor of one of Crossroads’ 13 campuses, said Edwards describes “people like me.”

Chuck Mingo speaks during the Faith, Race and Politics conference on Jan. 13, 2020 at the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center in Cincinnati, Ohio. RNS photo by Adelle M. Banks

“It would be nice to have some weekends where I could just fully express my feeling about what’s going on in the world without having to put it through 80 different filters of how I might communicate that in a way that doesn’t unnecessarily alienate people,” Mingo said, sitting next to Crossroads’ white senior pastor, Brian Tome.

Though Mingo said he sometime senses a lack of trust from some blacks he meets outside Cincinnati who learn of his role, he added that he takes comfort in knowing other “estranged pioneers.”

Edwards, in an interview, said that being part of a multiracial church does not automatically presume an openness to discussions of race, and racist assumptions about sharing power can be and often are still in effect.

“You can have diversity and still have white supremacy,” said Edwards, author of “The Elusive Dream: The Power of Race in Interracial Churches.” “It’s very hard emotionally and spiritually and so we have to be very honest about what it’s doing to people’s souls, being in environments that say one thing and in reality living out another.”

Leaders and observers of multiracial churches say the congregations go through stages. In tense times, some will have members walk out while others lean in. Disagreements can sprout up about race, politics or music. Some congregations can’t bridge these divides and close.

But others survive and grow, said Corey J. Hodges, the Salt Lake City pastor who talked at Mosaix about grappling with how to address national racial tensions with his congregation. He said he’s grateful for the variety of perspectives that homogenous congregations never hear.

Derwin Gray. RNS photo by Adelle M. Banks

Though his church life has been “stressful,” he said in an interview, “I’m OK with that because that pain is a part of the growth.”

For others, national discussions about race present opportunities. A former defensive back for the Indianapolis Colts and Carolina Panthers football teams, Derwin Gray now leads Transformation Church in Indian Land, South Carolina, which he said is about 58% white and 35% African American.

His sermon on the Kaepernick kneeling controversy focused on his own “hurt” that some Christians didn’t think players should kneel at the national anthem. The gesture was an attempt at “protesting injustice so America could live up to her ideal.” Such a sermon about the need to care about others’ concerns “isn’t unusual” at his nondenominational church, said Gray, who is black.

“My point was that as brothers and sisters in Christ, we are to, as Philippians 2:4 says, consider others better than ourselves. So what hurts you should hurt me and what hurts me should hurt you.”

Matthew J. Cressler contributed to this report.