U.S. Supreme Court building

WASHINGTON (AP) — For a Supreme Court that says it has an allergy to politics, the next few months might require a lot of tissues.

The court is poised to issue campaign-season decisions in the full bloom of spring in cases dealing with President Donald Trump’s tax and other financial records, abortion, LGBT rights, immigration, guns, church-state relations, and the environment.

The bumper crop of political hot potatoes on the court’s agenda will test Chief Justice John Roberts’ insistence that the public should not view the court as just another political institution.

“It’s interesting that all of this is coming together in an election year. The chief justice has made it clear that people should view the court as a nonpolitical branch of government and people tend to have the opposite view when they see these big cases,” said Sarah Harrington, who has argued 21 cases in front of the high court.

The justices are gathering on Friday for the first time in nearly a month to put the finishing touches on opinions in cases that were argued in the fall and decide what new cases to take on. Most prominent among the possibilities is the latest dispute over the Obama-era health care overhaul.

Chronic pain

No matter how many times the Supreme Court upholds the law commonly known as “Obamacare,” a new challenge seems to arise. This time, a federal judge in Texas struck down the entire law in 2018 when he ruled that Congress’ decision to eliminate the financial penalty for not having insurance rendered the health insurance requirement unconstitutional.

Even though lawmakers changed only the one provision and left the rest of the massive law in place, U.S. Judge District Judge Reed O’Connor held that the entire law had to go. The lawsuit was filed by Texas and other Republican-dominated states. The federal appeals court in New Orleans agreed with O’Connor about the insurance requirement, but ordered him to redo his analysis about the rest of the law.

The Trump administration, which has long tried to kill the law, is on Texas’ side, although its view of how much of the law should be stricken is muddled.

Democratic-led states and Democrats in Congress appealed to the Supreme Court, urging the justices to take up and rule on the case by the end of June. The suit already is resulting in damaging uncertainty about the future of the law, the Democrats said.

If the justices take the rare step of scheduling arguments for May in advance of a decision in June, they almost certainly will act quickly, probably on Friday, to let both sides get work on a tight deadline.

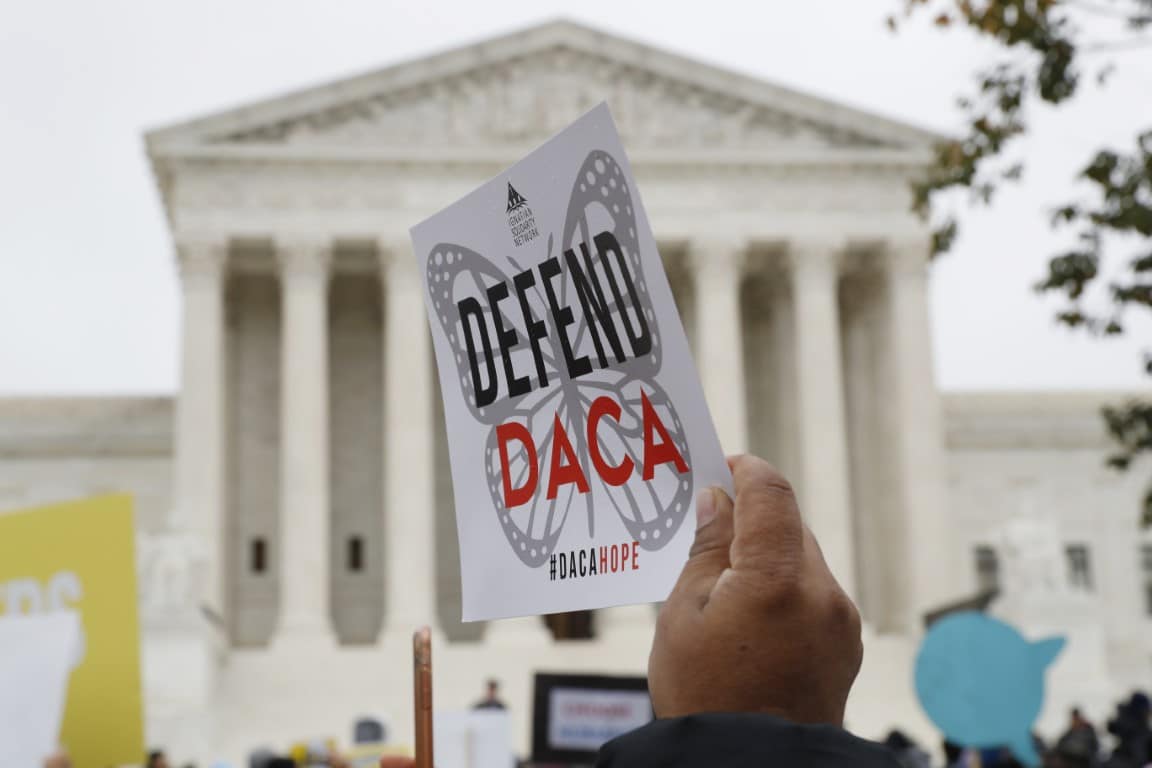

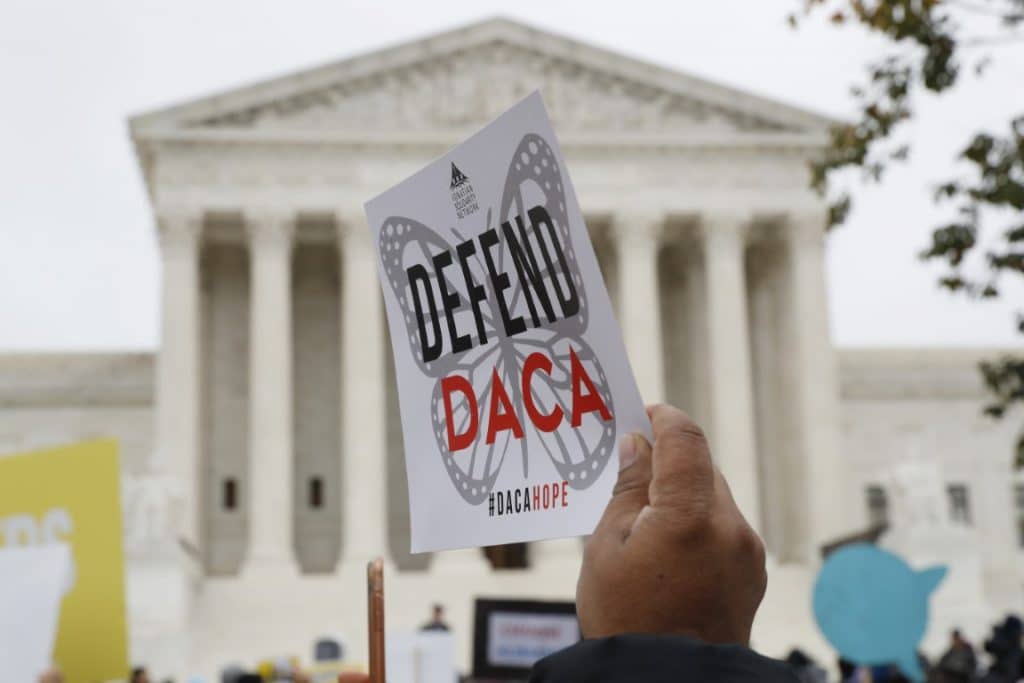

People rally outside the Supreme Court as oral arguments are heard in the case of President Trump’s decision to end the Obama-era, Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program (DACA), at the Supreme Court in Washington on Nov. 12, 2019. DACA recipients are assuming a prominent role in the presidential campaign, working to get others to vote, even though they cannot cast ballots themselves, and becoming leaders in the Democratic campaigns of Bernie Sanders and Tom Steyer as well as get-out-the-vote organizations. (AP Photo/Jacquelyn Martin, File)

Works in progress

The biggest unresolved issues from the fall involve LGBT rights, immigration, and guns.

The court is considering whether the federal civil rights law known as Title VII that prohibits workplace discrimination because of sex, among several categories, protects LGBT people. When the justices heard arguments in October, it appeared that Justice Neil Gorsuch might be open to joining with the four liberal justices to rule for the workers.

In November, the court took up the administration’s decision to end an Obama-era program that provides work permits to roughly 700,000 immigrants in the country illegally who were brought to the United States as children. The Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, or DACA, also shields recipients from deportation. The administration has sent mixed messages about whether it will aggressively seek to deport DACA recipients if it wins at the high court.

The Supreme Court heard arguments in December in a dispute over a New York City ordinance that barred people from transporting legally owned, unloaded and locked handguns from their homes to shooting ranges or second residences outside the city. Changes in city and state law since the court agreed to hear the case may lead the justices to dismiss the case, which had seemed poised to be the court’s first significant gun rights decision in 10 years.

Only four cases have been decided so far this term, a slower pace than normal. One reason may be that the two recent Trump appointees, Gorsuch and Justice Brett Kavanaugh, may be less predictably conservative than advertised, said Jonathan Adler, a professor at the Case Western Reserve School of Law in Cleveland.

Last term, in decidedly less significant cases, there were varying lineups of justices in 5-4 decisions. “Last term shows there’s some unpredictability that we might not have anticipated,” Adler said.

Anti-abortion activists rally outside of the U.S. Supreme Court, during the March for Life in Washington, on Friday, Jan. 24, 2020. (AP Photo/Jose Luis Magana)

Constitutional clashes

Four years ago, the court struck down a Texas law regulating abortion clinics because it placed an “undue burden” on women seeking an abortion, in violation of their constitutional rights. In arguments on March 4, the justices will weigh an essentially identical law from Louisiana. The only difference is a big one — the makeup of the court, most notably, the retirement of Justice Anthony Kennedy and his replacement by Kavanaugh.

Both sides of the abortion debate are watching closely to see if the five Republican-appointed justices — Samuel Alito, Clarence Thomas, Roberts, Gorsuch and Kavanaugh — are willing to take the first steps in a retreat from protecting the right to abortion that the Supreme Court first announced in 1973.

At the end of March, the court will take up the most politically sensitive cases of the term, Trump’s effort to kill subpoenas from Congress and the Manhattan district attorney for his tax, bank and other financial records. The president is making broad arguments that he can’t even be investigated during his term in office. Rulings against the president could result in the quick release of personal financial information in the heat of his reelection campaign. The records are held by banks and an accounting firm.

Impeachment aftermath

Roberts had less of a break than his colleagues because he presided over Trump’s impeachment trial in the Senate, which ended with the president’s acquittal on charges he abused his power by tying aid to Ukraine to that country’s investigation of his political rivals and obstructed Congress’ investigation.

One intriguing question is whether the process will affect the chief justice’s work at the court. At several turns, Trump’s lawyers argued during impeachment that House Democrats should have gone to court to seek documents they wanted. But in court cases, Trump’s legal team or the Justice Department says courts should stay out of political disputes between the White House and Congress.

Roberts also called out both sides at one point for their intemperate remarks and later declined to read questions from Sen. Rand Paul, R-Ky., that allegedly revealed the name of the whistleblower who first raised concerns about Trump and Ukraine.