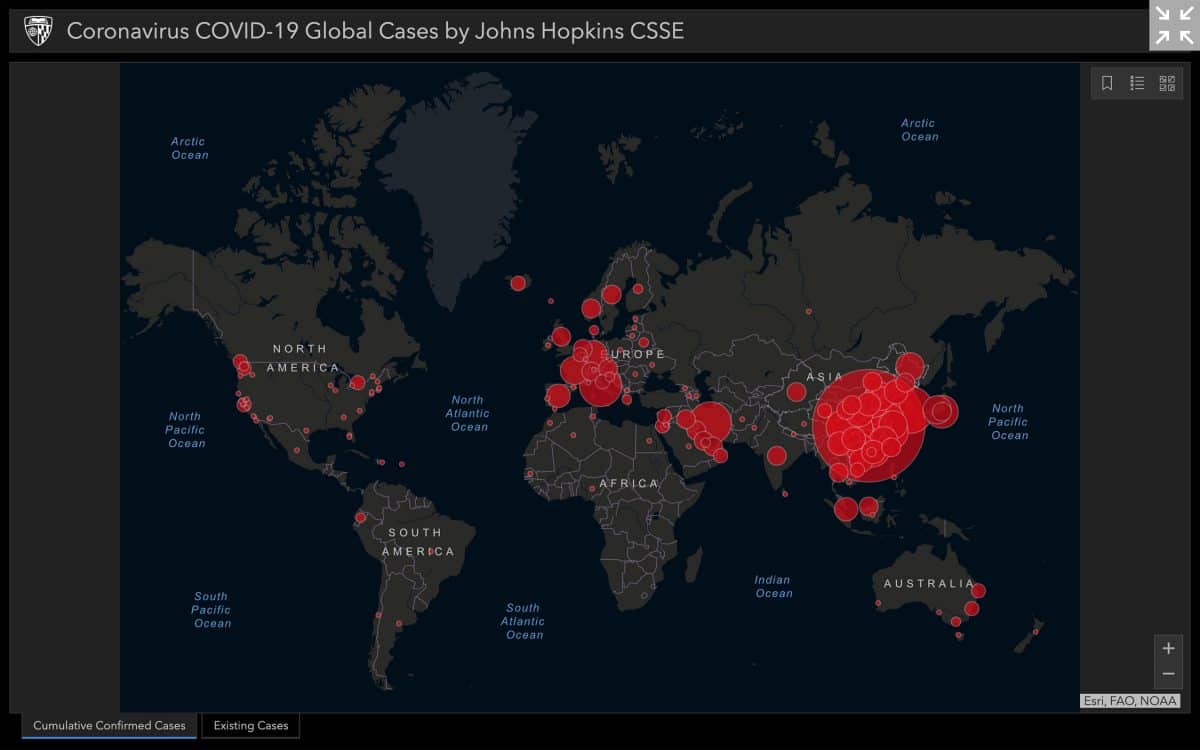

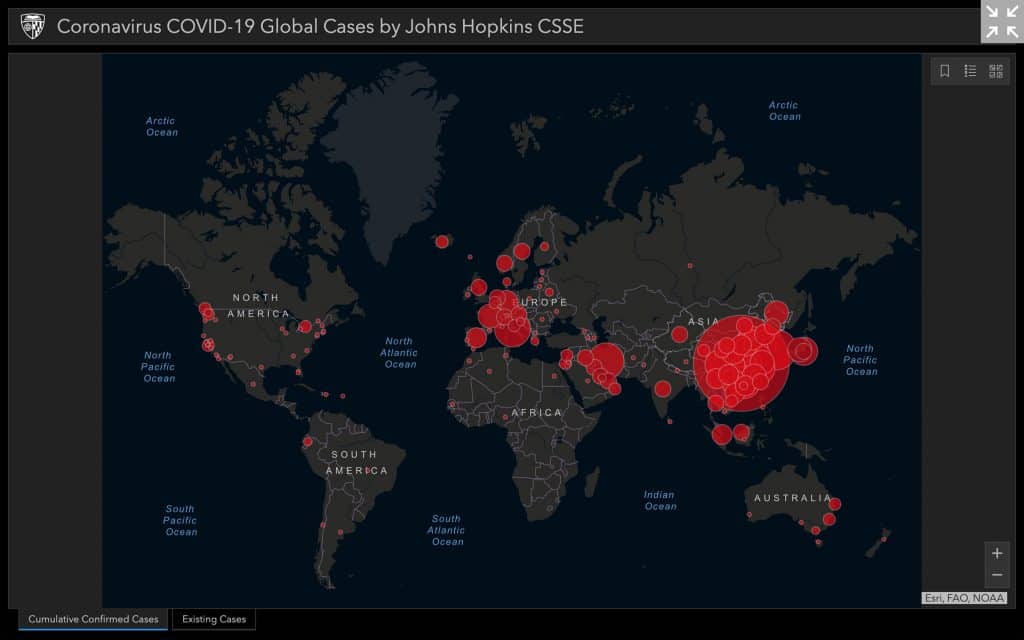

An interactive map of Cumulative Confirmed Cases of Coronavirus COVID-19 Global Cases by Johns Hopkins CSSSE on March 4, 2020. Screengrab

(RNS) — More than 40 years of research on the psychology of surviving disasters has found that religion can be a valuable resource in fostering resilience. While religion has generally been connected to positive outcomes, studies of people’s reactions to the Ebola outbreak and Syrian refugee crisis show that some forms of religiosity may be less healthy and less helpful.

These reactions may help us predict how religious people in the United States may react to the present spread of the coronavirus.

A few years back, our team at the Humanitarian Disaster Institute set out to discover why Americans seemed mostly unconcerned when thousands of cases of the Ebola virus were reported in Africa, but panicked after the first couple of cases were diagnosed in the United States. Led by Daryl Van Tongeren, an associate professor of psychology at Hope College, our team looked at what we could learn about how religion might impact people’s responses to public health threats, outbreaks and pandemics.

The evidence pointed to what social psychologists refer to as terror management theory, the idea that human beings will go to great lengths to avoid reminders of their own mortality. We do this as a way to manage our anxiety.

In our lab-based study of Ebola as an existential threat, we found that individuals high in “extrinsic religiosity” — those who tend to engage religion for its personal and social benefits, like emotional security and strengthened in-group ties — reported more fearful responses. These individuals “were especially likely to experience Ebola reminders as an existential threat that intensified national-security concerns,” such as supporting strict travel bans, border security and immigration laws, the study said.

We saw the opposite effect among participants who scored high in “intrinsic religiosity” — those motivated by a religious framework who attempt to live out their faith accordingly. These individuals for whom their faith appeared to be more central to their daily life reported less fearful views.

These findings led us to conclude that “Taken together, large-scale existential threats may be especially likely to intensify pro-ingroup/anti-outgroup biases among extrinsically religious individuals.”

In another Humanitarian Disaster Institute study led by psychologist Marianne Millen Carlson, our team found similar fear-driven responses to Syrian refugees among participants high in extrinsic religiosity. At the height of the refugee crisis in 2016, we surveyed more than 800 people from across the United States and found that individuals who primarily adhere to religion for personal gains demonstrated higher levels of prejudicial attitudes toward the refugees. As in our Ebola study, those participants also reported feeling more threatened.

Conversely, in both studies intrinsically religious participants, for whom religion was more central to their daily lives and who sought to live by their religious beliefs, reported less fearful responses and had lower levels of concern over national security issues.

What is particularly important about our refugee study is that it showed that those who are extrinsically religious were not only more likely to report feeling threatened, but prejudice toward Syrian refugees. They were more likely to report negative and biased attitudes toward the refugees as a group because they considered refugees to be different from the people they self-identified with.

A quick skim of headlines reveals that some panic has already been triggered, mostly in the form of citizens buying up face masks and other protective items that don’t do much to prevent the disease or aren’t really necessary. But people of Asian descent are also reportedly already facing prejudice and discrimination regardless of which country their forebears came from because the coronavirus outbreak had its origins in China.

Collectively, our findings suggest that if the coronavirus continues to spread in the U.S. over the coming weeks and months, we can look for a significant swath of Americans — especially those more motivated by an externalized faith — to feel more threatened by the outbreak, and to translate that into discrimination against groups they perceive as different.

Now is also the time for U.S. religious leaders and religious communities to begin to think about how to prepare their people and communities for the coronavirus.

As they do, our faith leaders need to lead the way in reminding people of faith that documented cases in the U.S. currently are very low in number. ( See a dashboard of all known cases around the globe.) While clergy encourage people to wash their hands before coming to services and to stay home if they feel ill, they might also encourage others to live out their faith more intrinsically, to faithfully prepare, and to reject fear-driven panic, stigmatization and prejudice.