The First Baptist Church in America in Providence, R.I., in 2007. Photo by J. Stephen Conn/Creative Commons

(RNS) — I walked through the doors of First Baptist Church of Mount Vernon, Illinois, a congregation that I’ve pastored for the last 13 years, and shook hands with the 91-year-old greeter. Afterward, she said to me, “I didn’t know if we should shake hands today.”

I hadn’t even thought about it, but I know that she had.

COVID-19 has now infected more than 100,000 people, killing 4,000 of them across the globe. But, one of the real curiosities is that the mortality rate is dramatically different based on age. The disease takes the life of nearly 15% of the people that it infects over the age of 80.

I find that to be incredibly cruel, especially for my mainline church that has been dwindling in size and increasing in age at a stunning rate. Of our 20 or so active members, four of them are over the age of 90. Another 10 are in their 80s. If COVID-19 becomes a true global pandemic, my church would likely not fare well.

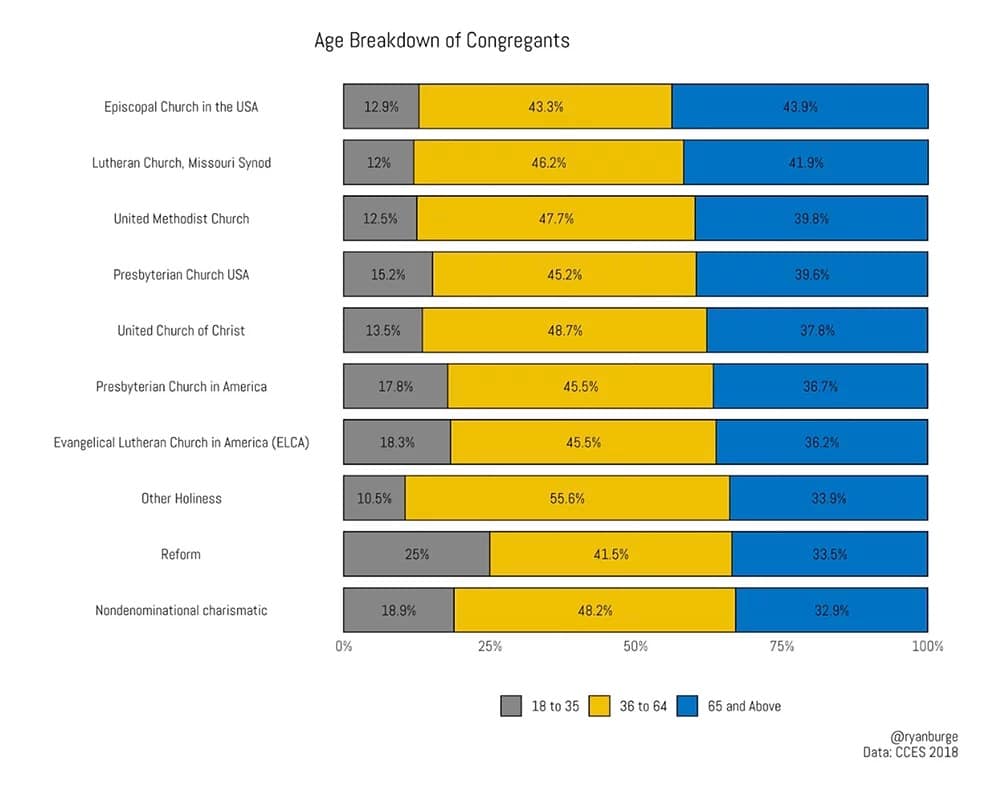

That’s true for many of our mainline brothers and sisters as well. A quick calculation shows that of the 10 religious traditions in the United States that have the oldest members, the top seven are mainline Protestant traditions. Nearly half of all Episcopalians are over the age of 65, with an average age of 59 years old, according to data from NORC’s General Social Survey. That’s an increase of six years since the first decade of this century.

It’s not much better for Lutherans (ELCA or Missouri Synod) or for the United Methodist Church, the country’s second largest Protestant tradition, which is home to three retired people for every member who is under the age of 35.

“Age Breakdown of Congregants” Graphic courtesy of Ryan Burge

Demography is destiny for many of these denominations. They will become dramatically smaller in the next two decades based on attrition alone, whether or not they are hit by COVID-19.

But if the disease can’t be curtailed, it could become a turning point for some of these denominations: Their houses of worship are prime targets for the spread of disease.

While the act of taking the body and blood of Jesus may have great spiritual benefit to church members, it is an ideal vector for being contaminated by a virus like COVID-19. At Christ Church, an Episcopal congregation in Washington, D.C., the rector, as Episcopalians call their senior pastor, may have unknowingly exposed more than 500 people to the virus while distributing the bread and wine last weekend. Those who attended have been asked to self-quarantine by District of Columbia authorities.

Southern Baptist churches like the one that I grew up in placed very little importance on the practice of Communion. We took it once a quarter in my home church. Often, it was done on Sunday evening. In mainline traditions, Communion is often the centerpiece of the weekly worship service. They may forgo it for practical reasons, but it will no doubt make worship feel emptier.

This illustration provided by the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in January 2020 shows the 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV). Image courtesy of CDC

Judging from the restrictions now in force in Italy, where people in line at the grocery store are being kept 3 feet apart, sitting in church at all seems could become a danger. The idea of Catholic churches with handfuls of their often gray haired members sitting an arm’s distance apart is heart-wrenching. I have always believed that the act of Communion is not just creating a connection between the human and the Divine, but also as a powerful way for each person to affirm that they are not alone in this world. We take the elements together — not 3 feet apart.

Connection to their fellow members is especially important for older Americans. Data from Pew Research Center indicates that the average 80-year-old spends at least eight hours a day alone, double the time a 40-year-old does. For many of the older generation, the institutions that held society together for them during the formative years have already crumbled. One of the few things that has remained constant for them is their church home, seeing the same people in the same pews every Sunday, taking the bread and drinking from the cup the same way they have done for decades. They need that consistency and community — and COVID-19 might take that away from them.

For my church, where we take Communion only on the first Sunday of the month, I’m worried that the virus is going to spread exponentially by the first week of April and that I will have to make a difficult choice of whether to administer the elements. I want my aging yet faithful congregation to taste and see that the Lord is good, but I don’t want to put their health at risk to do so.