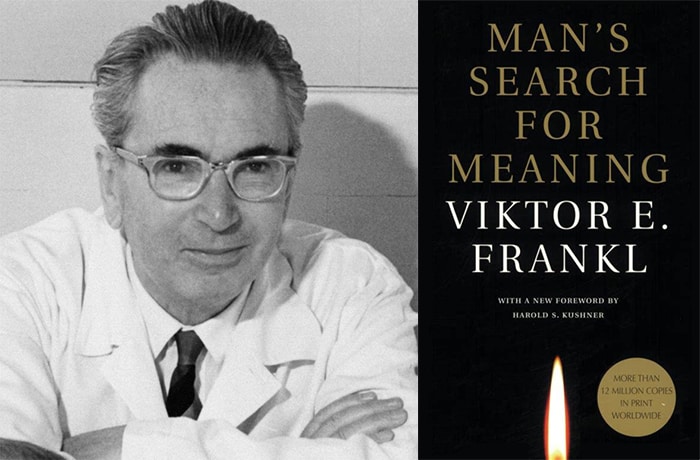

Viktor Frankl in 1965 photo and the cover of his book, Man’s Search for Meaning.

Seventy-five years ago, on March 26, 1945, Viktor Frankl celebrated his 40th birthday in the worst conditions imaginable — confined to a concentration camp in Dachau, Germany. Before the year was over, however, not only had he been liberated but he had also written an international bestselling book.

Leroy Seat

Living in Terrible Times

Currently, many countries of the world are living in a time of fear and anxiety — and of death — because of the novel coronavirus known as COVID-19. This new pandemic certainly should not be downplayed, but the circumstances in which Viktor Frankl lived in 1944-45 were far worse.

Frankl was born in Vienna, the child of Jewish parents. Being a Jew was no particular problem there—until the invasion of Austria by the Nazis in 1938. Three years later Frankl married Mathilde Grosser, and the very next year they were arrested by the Nazis.

In 1944 Frankl and his wife were transported to Auschwitz. Later, Mathilde was moved to another camp, and the next year she died of typhus at the age of 24. Frankl was also moved to a concentration camp in Dachau.

The suffering and death toll in those prisons are almost incredible — but Frankl managed to live through that terrible time and was able to tell the story of the suffering he observed and experienced in the concentration camps.

Finding Meaning in Terrible Times

Near the end of April 1945, Frankl and his fellow prisoners were liberated. He then returned to Vienna and, among other things, wrote a book that was published the next year. The English translation was first published in 1959. Three years later it was issued again under the title Man’s Search for Meaning: An Introduction to Logotherapy. (A short illustrated summary of the book can be found on YouTube.)

Near the end of April 1945, Frankl and his fellow prisoners were liberated. He then returned to Vienna and, among other things, wrote a book that was published the next year. The English translation was first published in 1959. Three years later it was issued again under the title Man’s Search for Meaning: An Introduction to Logotherapy. (A short illustrated summary of the book can be found on YouTube.)

By the time of his death in 1997, Frankl’s superlative book had sold more than 10 million copies and had been translated into 24 languages.

As early as 1926, Frankl had used the word logotherapy, the term that came to characterize what is called the Third Viennese School of Psychotherapy, preceded by the work of two other great Austrian psychiatrists: Sigmund Freud (1856~1939) and Alfred Adler (1870~1937).

Logotherapy emphasizes the importance of finding meaning in one’s life. Thus, Frankl emphasized the will to meaning in contrast to the will to pleasure as found in Freudian psychoanalysis and the will to power as stressed by Adlerian psychology. (An interview with Frankl in 1963 on “Why Meaning Matters” is available here.)

As Frankl elucidated, “It is one of the basic tenets of logotherapy that man’s main concern is not to gain pleasure or to avoid pain but rather to see a meaning in his life. That is why man is even ready to suffer, on the condition, to be sure, that his suffering has a meaning” (2014 ed., p. 106).

Suffering, Frankl saw, has meaning when it helps people learn new truths and when it makes them stronger. He wrote about citing Nietzsche in a talk he gave to the 2,500 men in his camp: “That which does not kill me, makes me stronger.”

What about These Terrible Times?

There are many differences and some similarities between the current COVID-19 pandemic and the concentration camps Victor Frankl experienced in 1944-45. The suffering was greater for most of the population there and the death rates much, much higher.

But rather than a relatively small population in a very small area, the current pandemic is worldwide and is affecting, or likely soon will affect, large numbers of people in countries around the world. In fact, COVID-19 threatens to devastate poor countries.

For most of you who read this, up until now the pandemic has been mainly an inconvenience. Some, however, may already be suffering financially. But as the weeks go by, some of you may have friends or family members who become ill — and some of us may become ill with the virus ourselves.

In these trying times, let’s heed Frankl’s counsel to keep being thankful for the blessings of the past and to keep searching for meaning, which makes it possible to be resolute in the present and hopeful for the future.

A version of this article first appeared on Seat’s blog, The View from This Seat. It is used with permission.