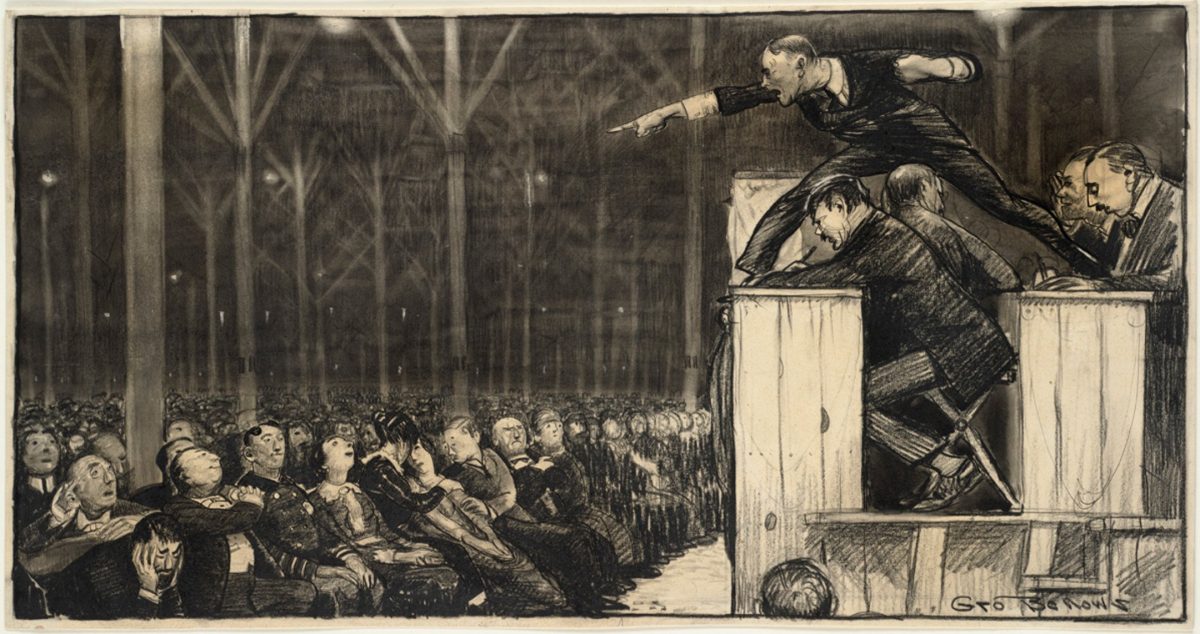

Billy Sunday preaches on March 15, 1915, in a temporary tabernacle erected on the site of the Central Library of the Free Library of Philadelphia. Illustration by George Bellows. Metropolitan Magazine, May 1915. Image courtesy of Boston Public Library/Creative Commons

(RNS) — As the United States deals with the social effects of COVID-19, several states with stay-at-home orders have exempted religious services. Some evangelical churches, claiming their First Amendment right to worship, held religious services on Easter with the full knowledge that the virus spreads through close human contact.

History will do little to sway the pastors of these churches. Nor should we expect history to provide definitive answers as to whether it is a good idea for churches to remain open during pandemics.

But history can serve as a moral guide in times of crisis. Mark Twain is reputed to have said, “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes.” In that spirit, it is worth remembering evangelist Billy Sunday’s face-to-face encounter with the great influenza pandemic while conducting a revival crusade in Providence, Rhode Island.

Sunday was one of America’s most popular personalities during the first two decades of the 20th century. A former baseball player, he left his dreams of big-league fame to devote himself to a life of evangelism. He preached the simple gospel: Jesus died for the sins of the world, rose from the dead Easter morning and offers eternal life to those who believe in his redemptive work.

Preacher Billy Sunday, left, at White House on Feb. 20, 1922. Photo courtesy of LOC/Creative Commons

Sunday delivered his message with the flair of a vaudeville showman. He flailed his arms, jumped up and down, stood atop his pulpits and slid across the stage, reminiscent of his baseball days. A Billy Sunday meeting was entertainment with an altar call. His crusades were major events in the life of early 20th century American cities.

Sunday held 70 revival meetings in Providence between Sept. 21 and Nov. 17, 1918. He preached most of his sermons in a 7,000-seat, makeshift wooden tabernacle built on Princeton Avenue in the city’s Elmwood section.

He preached against sin, the devil and the evils of “demon rum” (he was a strong advocate of Prohibition), but Billy Sunday confronted a new enemy in Providence. The so-called Spanish flu had already reared its ugly head earlier in the year, but a second wave was on the horizon. Sunday would not go down without a fight. He was quick to inform his audience about the true cause of this pandemic:

“We can meet here tonight and pray down an epidemic just as well as we can pray down a German victory. The whole thing is a part of their propaganda; it started over there in Spain, where they scattered germs around, and that’s why you ought to dig down all the deeper and buy more Liberty bonds. If they can do this to us 3,000 miles away, think of what the bunch would do if they were walking our streets. There’s nothing short of hell that they haven’t stopped to do since the war began — darn their hides.”

In 1918, Sunday blamed the Germans. Today, Liberty University president Jerry Falwell Jr., an evangelical leader whose family traces its religious genealogy to the kind of evangelicalism Sunday espoused, recently suggested that the coronavirus was a North Korean and Chinese attempt to undermine Donald Trump. Old evangelical habits die hard.

As we look back on Sunday’s visit to Providence from the perspective of our current pandemic, the view is troubling. Newspapers ran stories about the death of Providence citizens alongside reports of Sunday’s crusade. The Congregationalist and Advance, a religious magazine, claimed that 10,000 people “grasped Mr. Sunday’s hand” during the crusade. People collapsed with the flu as Sunday preached. A few days after leaving Providence to close up the family summer home in Winona Lake, Indiana, Sunday’s wife, Helen “Ma” Sunday, contracted influenza. (Sunday kept preaching).

Billy Sunday, circa 1910. Photo courtesy of Creative Commons

On Oct. 5, a Sunday, the Board of Aldermen closed schools, theaters, dance halls and most religious services, but Providence Mayor Joseph Gainer allowed Billy Sunday to hold three services. They were all packed.

But when the Providence Board of Aldermen closed all the city’s public venues two days later, Sunday submitted to their authority: “It is up to us to hope and pray,” Sunday told his audience. “We are always willing to help anything that is for the public good and do it cheerfully. There is nothing drastic in the (aldermen’s) order, and it is issued in an attempt to stamp out this epidemic.”

After the Providence meetings were put on hold, Sunday took a train to Boston, where he preached to and mingled with 40,000 soldiers at Camp Devens (now Fort Devens).

Influenza hit Providence hard. In October alone, 6,000 people in the city got sick. Nearly 1,000 died over the course of the pandemic. When the virus eventually faded, Providence reopened schools and public places and the Sunday crusade continued. The Congregationalist and Advance noted that Sunday preached to a “quarter of a million listeners” during his visit.

Sunday’s Providence crusade leaves today’s evangelicals with some important lessons. Sunday gladly submitted to government authority by closing his crusade during the height of the pandemic. Yet, in our current world of social distancing, one can’t help but wonder how much Sunday contributed to the spread of the epidemic.

In an article recapping the crusade, The Christian Advocate quipped: “We are not sure but that influenza (preached) to more people than Billy Sunday ever did. … ”