In this Sunday, April 23, 1995 file photo, the Rev. Billy Graham speaks to the capacity crowd at a prayer service at the State Fair Arena in Oklahoma City, for the victims of Wednesday’s fatal car-bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in downtown Oklahoma City. (AP Photo/Wilfredo Lee)

OKLAHOMA CITY (AP) — Search-and-rescue workers came straight from the blast site, hard hats atop their heads and mud and grime on their boots.

Relatives of the missing joined loved ones of those already confirmed dead in holding teddy bears and wiping tears as this grieving heartland city — indeed, the entire shaken nation — came together to pray.

On a somber Sunday 25 years ago, the late Rev. Billy Graham shook off the flu to try and explain how a loving God could have allowed the April 19, 1995, bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building to occur.

But Graham — America’s pastor-in-chief — had no answer.

An unidentified boy leans over during the prayer service where some 20,000 people overflowed the State Fairgrounds. President Clinton and the Rev. Billy Graham addressed the memorial service on what the president declared a national day of mourning. (AP Photo/Beth A Keiser)

“I appreciated him saying, ‘I don’t know why,’ that this was something we were not going to understand,” said Lynne Gist, whose sister, Karen Gist Carr, 32, was among the 168 dead in what remains the deadliest act of domestic terrorism in U.S. history.

Despite the lack of answers, the April 23, 1995, prayer service — four days after the bombing — began the healing process for this Bible Belt state and millions of TV viewers around the world.

“It was a time when it didn’t matter if you were red or blue, Republican or Democrat,” said Kari Watkins, executive director of the Oklahoma City National Memorial and Museum. “We were just Americans, and we came together and leaned on our faith as one of the first steps to get over this, and I don’t think we have ever looked back.”

Rod Masteller, a Southern Baptist pastor who gave the invocation at the service, said: “Even as we’re seeing today with the coronavirus, pain and suffering have a way of bringing people with different points of view together. And I believe that’s probably exactly what happened then. We were all just coming together to pray.”

___

A wall near the bombing memorial’s Survivor Tree — an American elm that survived the blast — displays these words that Graham spoke that day: “The spirit of this city and nation will not be defeated. Our deeply rooted faith sustains us.”

But that spirit was sorely tested in those April days.

Four days before Graham stood before a grieving audience, Gulf War veteran Timothy McVeigh parked a yellow Ryder rental truck filled with 5,000 pounds of explosives outside the nine-story building downtown and got into a getaway car. The timed fuse ignited at 9:02 a.m.

McVeigh and co-conspirator Terry Nichols would be convicted in the bombing. McVeigh was executed in 2001. Nichols remains behind bars, serving a life sentence at the federal supermax prison in Florence, Colorado.

The prayer service came together quickly in the wake of the bombing. It started with Cathy Keating, wife of then-Oklahoma Gov. Frank Keating, a Republican inaugurated just a few months earlier.

In a talk with a friend the night of the bombing, the first lady expressed how helpless she felt. She wondered what, if anything, she could do.

The friend asked Keating what she would have done in the past, if something tragic had happened in her personal life.

“Well, we’d have a prayer vigil,” replied Keating, who — like her husband — is Roman Catholic.

When the weary governor returned home that night after a long day of chaos, he heard women’s voices.

Their chatter on such a devastating day frustrated him.

“So I went upstairs, and I said, ‘What’s going on here?’” recalled Frank Keating, Oklahoma’s top elected official from 1995 to 2003. “It’s like, ‘Don’t you realize we’re in a huge, tragic, horrifying, shattering experience?’

“And Cathy looked up at me — this is no lie — and she said, ‘We are planning a memorial service, a prayer service, at the fairgrounds. And you can leave.’”

Weeks earlier, Cathy Keating had connected with Laura Bush, wife of the new Texas governor, George W. Bush, at a meeting of first ladies in Puerto Rico. The two wives had attended an island crusade where the Rev. Graham, then 76, preached.

Keating knew that she wanted Graham to speak at the Oklahoma vigil. However, when she called the famous evangelist’s office in North Carolina, she learned he had been ill.

Still, when she got him on the phone, Graham agreed without hesitation to come.

“He could hardly walk. He was still so weak,” Cathy Keating said. “Frank and George (Bush) took his arms to help him.”

But when the time came for Graham to step on stage, God’s spirit seemed to rejuvenate him, she said, “It was unbelievable, and it was visual. He was strong, and his message was powerful. Not one person could tell he was sick.”

Lynne Gist looks out of the front door of her home Wednesday, April 15, 2020, in Midwest City, Okla. Gist lost her sister, Karen Gist Carr, on April 19, 1995, when a truck bomb ripped through the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in downtown Oklahoma City and killed 168 people. Due to COVID-19 concerns, the Oklahoma City National Memorial and Museum scaled back its plans for a 25th anniversary remembrance. (AP Photo/Sue Ogrocki)

Roughly 20,000 people — including relatives carrying photos of family members still missing in the rubble — filled Oklahoma City’s State Fair Arena and nearby overflow spaces.

Florists donated thousands of red and yellow single-stem roses for the attendees. Brenda Edgar, wife of then-Illinois Gov. Jim Edgar, sent hundreds of teddy bears — and then hundreds more at Cathy Keating’s last-minute request.

President Bill Clinton and many others wore multicolored ribbons: white for the dead, yellow for the missing, purple for the children and blue for the state of Oklahoma.

President Bill Clinton and first lady Hillary Clinton stand with families of victims of the bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building during a prayer service at the State Fairgrounds in Oklahoma City. The man next to the president holds teddy bears, given to children of affected families. (AP Photos/Lacey Atkins)

Clinton, a Democrat who drew only 34 percent of the 1992 popular vote in the conservative Sooner State, flew from Washington to offer his condolences and praise the strength and resiliency of Oklahomans. He got a standing ovation.

The youthful-looking president promised that America would do all it could to heal the injured, rebuild the city and bring justice to those responsible for “this terrible sin.”

“If anybody thinks that Americans are mostly mean and selfish, they ought to come to Oklahoma,” said Clinton, who was joined by first lady Hillary Rodham Clinton. “If anybody thinks Americans have lost the capacity for love and care and courage, they ought to come to Oklahoma.”

Graham, who died Feb. 21, 2018, at the age of 99, told the crowd the bombing “was like a violent explosion ripping at the bare heart of America, and long after the rubble is cleared and the rebuilding begins, the scars of this senseless and evil outrage will remain.”

“I’ve been asked why God allows it,” he said during his sermon. “I don’t know. I can’t give a direct answer. I have to confess that I never fully understand, even for my own satisfaction. I have to accept that God is a God of love and mercy and compassion even in the midst of suffering.”

Cathy Keating’s voice cracked as she stood on the fairgrounds arena stage, awash in carnations, lilies and tulips, and reflected on the innocence — and lives — lost by the state’s children.

“Some are dead, some are missing, and all of them — no matter where they may have been on Wednesday — are tragically wounded,” the governor’s wife told the crowd. “It is a terrible crime to steal a child’s trust in the goodness of humanity.

“We have to hold our children close through the nightmares to come. We have to teach them that evil is not the norm. And we begin that process today.”

Although the final count was unknown at the time, 19 children died in the bombing, many of them inside the second-floor America’s Kids day-care center.

In this Sunday, April 23, 1995 file photo, a capacity crowd attends the prayer service at the State Fair Area in Oklahoma City for the victims of Wednesday’s fatal car-bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in downtown Oklahoma City. (AP Photo/Wilfredo Lee)

As mourners sang “Amazing Grace” and “God Bless America” and heard from a Catholic archbishop, a nondenominational Christian pastor and a rabbi, rescue workers had already cleared more than 100 tons of concrete and steel from the bombing site.

The official death toll stood at 78.

Scores of victims remained missing and wouldn’t be recovered for days.

Relatives pleaded with God for a miracle, that their loved ones might somehow be found alive in the rubble.

“You just hold out hope until you absolutely can’t,” said Lynne Gist, whose sister worked as an advertising assistant with the Army’s recruiting battalion on the fourth floor.

The body of Karen Gist Carr — remembered as a “people person” who embraced life — would be one of the last discovered in the two-week rescue effort.

Her parents and four older sisters — including Lynne Gist — all attended the prayer service.

The family welcomed the opportunity to be with fellow mourners. They appreciated the organizers’ effort to offer comfort and solace.

“It helped from the standpoint that there was support from people … trying to help in the best way they could,” said Lynne Gist, a Christian whose faith has helped her cope with her sister’s death. “We knew we weren’t alone in it.”

Lynne Gist walks through the Field of Empty Chairs at the Oklahoma City National Memorial and Museum, Wednesday, April 15, 2020, in Oklahoma City. Gist lost her sister, Karen Gist Carr, April 19, 1995, when a truck bomb ripped through the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in downtown Oklahoma City, killing 168 people. (AP Photo/Sue Ogrocki)

For Carr’s family, a sacred connection was forged with other bombing victims’ families at the 1995 prayer service — a holy link that Lynne Gist said has persisted through the years.

For a quarter-century, annual ceremonies on the bombing’s April 19 anniversary have emphasized faith and prayers.

In fact, three historic churches frame the memorial grounds: St. Paul’s Episcopal Cathedral, First United Methodist Church and St. Joseph’s Old Cathedral, a Catholic church. All were built at the time of the Oklahoma Land Run of 1889.

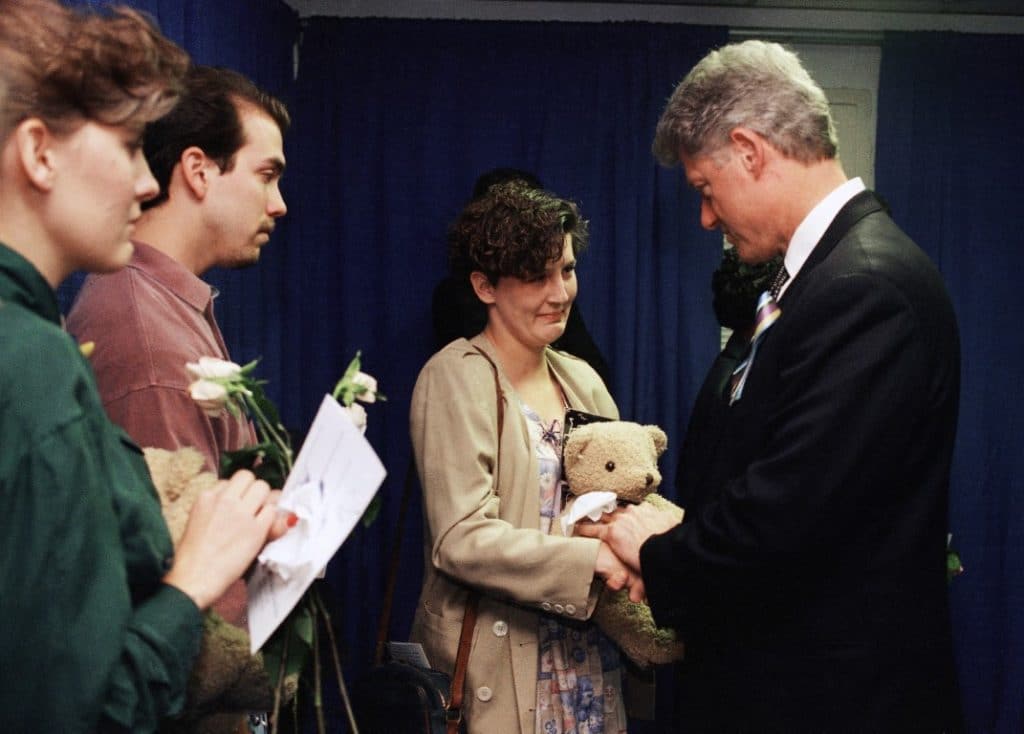

In this Sunday, April 23, 1995 file photo, Aren Almon of Oklahoma City, clutches a teddy bear as she is greeted by President Bill Clinton in Oklahoma City, Okla., after a prayer service for the victims of Wednesday’s deadly car bomb attack in downtown Oklahoma City. Almon’s 1-year old daughter, Baylee, was killed in the attack. (AP Photo/Pat Sullivan)

Lynne Gist and her family return to the bombing site year after year for simple reasons.

“We want her to be represented,” she said of her sister. “We don’t want this to be forgotten.”

The coronavirus pandemic has forced the temporary closing of the museum and will require a prerecorded video observance of the 25th anniversary, said Watkins, the memorial’s director.

Still, she said it’s fitting that the milestone date falls on a Sunday.

The taped rite will feature a spiritual message from Episcopal Church Presiding Bishop Michael Curry.

“We have used our faith in this 25-year journey to recover and to heal and to move forward,” Watkins said. “And that prayer service was the catalyst and set a standard for how we would remember and how we would lean into our faith in the darkest times.”

Associated Press religion coverage receives support from the Lilly Endowment through the Religion News Foundation. The AP is solely responsible for this content.