A portrait of James Boyce, the first president of Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, hangs in the president’s office in Louisville, Kentucky, in this December 2018 photo. (Adelle M. Banks/Religion News Service)

Last week, Southern Baptist Theological Seminary President Al Mohler sparked controversy as he endorsed President Donald Trump’s reelection. Many people expressed surprise at his move after he refused to back Trump in 2016. But should we really expect anything different from a man who continues to affirm the theology of slaveholders who damned people to hell on Earth just because of the color of their skin?

Brian Kaylor

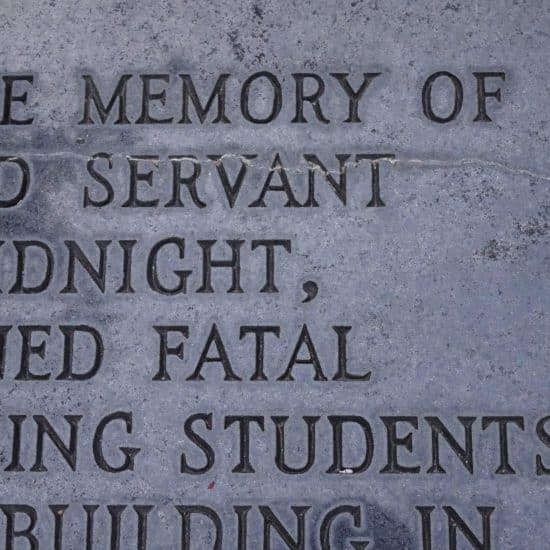

When SBTS took the important step of researching and acknowledging its slavery ties in a December 2018 report, they found that the four founders of the school enslaved more than 50 people. One of them, James Boyce, served in the Confederate Army. Another, John Broadus, presented resolutions to the Southern Baptist Convention in 1863 that pledged support for the Confederacy. And after the war, SBTS’s most important donor and trustee board chair, Joseph E. Brown, lavished funds on the school from a fortune largely built by the exploitation of black convict-lease laborers (or what scholars have called “slavery by another name”).

But despite all that, Mohler refuses to apologize or even question the biblical orthodoxy of the school’s founders. SBTS’s undergraduate school is still called Boyce College after the first slaveholding president of the seminary. The library also carries his name, and other buildings honor Broadus and the other two slaveholding founders, Basil Manly and William Williams. And as president, Mohler holds the position still known as the “Joseph Emerson Brown Professor of Christian Theology.” But more significantly, Mohler continues to praise the theology of those men.

Winston Churchill once remarked, “We shape our buildings, and afterwards our buildings shape us.” Another way of putting this might be that we reap what we sow. Or even more crudely is the old computing axiom: “garbage in, garbage out.”

How is theology shaped by attending a college named for a slaveholder, or studying books in a library named for one who served in the Confederate Army? How is theology shaped by sitting in a chair named for the man who defended slavery and then profited off the new form of slavery? And why would we not expect that shaped theology to present itself in political terms today?

Is this really a flip-flop for Mohler, or just a natural progression a Joseph Brown professor and a Boyce president?

Mohler insists that while slavery was wrong, that doesn’t discredit the theology of SBTS’s founders — even though they didn’t just enslave people but also advanced theological arguments to justify enslavement of blacks. Such hermeneutical gymnastics about the past prepared Mohler for his ethical compartmentalization of politics today.

“I gladly stand with the founders of the Southern Baptist Convention and The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in their courageous affirmation of biblical orthodoxy, Baptist beliefs, and missionary zeal,” Mohler wrote in 2015 right after noting SBTS slavery ties. “There would be no Southern Baptist Convention and there would be no Southern Seminary without them. James P. Boyce and Basil Manly Jr., and John A. Broadus were titans of the faith once for all delivered to the saints.”

I wonder how that “biblical orthodoxy” sounded to the ears of people under the whips. And I wonder how Mohler today sounds to black immigrants from what Trump called $#!%hole countries.

In SBTS’s 2018 report, Mohler called the four founders “defenders of biblical truth, the gospel of Jesus Christ, and the confessional convictions of this Seminary.”

I wonder how those “confessional convictions” felt to those families ripped apart at slave auctions. And I wonder how Mohler’s voting confession today feels to those families separated by Trump’s immigration policies targeting the people of color he often demonizes at rallies as subhuman.

And while Mohler said he laments the slaveholder past of SBTS’s founders, he refused to apologize on behalf of the institution. He also rejected calls that the school model biblical repentance by repairing the damage. Even worse, he did so by suggesting the black Baptist school in his town — which was founded by a formerly enslaved man at time when blacks were barred from SBTS — “denies or repudiates doctrines essential to biblical Christianity.”

I wonder how the racial theological arrogance of SBTS’s founders sounded to those trapped in a lifetime of bondage. And I wonder how Mohler’s echoing tone today feels to racial minorities as he endorses a man who called the racist tiki torch marchers in Virginia “very fine people.”

Voting is more than just something we do in the ballot box. We vote for the world we want each day by where we shop, what we buy, what we watch, what we affirm, and what we honor.

It’s easy to say today that slavery is wrong. But if we don’t unlearn our slaveholder theology embedded in our institutions, we’ll continue to make the same mistakes. As Mohler is now proving.