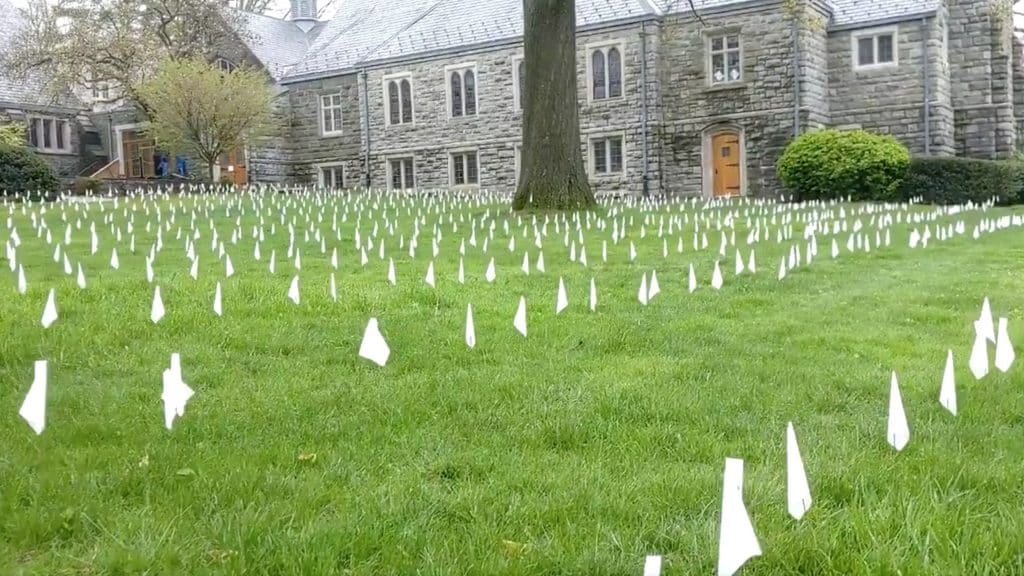

Pastor Patrick Collins has placed a white flag on the front lawn of the First Congregational Church in Old Greenwich, Connecticut, in honor of every COVID-19 victim in the state. Video screengrab via Paul P. Murphy

(RNS) — Recently, at one of his daily news conferences, Gov. Andrew Cuomo addressed the question that has haunted so many of us lately: How much is a human life worth?

“If it’s public health versus the economy,” he said, “the only choice is public health. You cannot put a value on human life. You do the right thing.”

While he was speaking, the PowerPoint display behind him flashed the answer to his query like a vintage MasterCard commercial:

Priceless.

Jewish tradition agrees with that wholeheartedly. While at times lives must be sacrificed for higher causes, such as a defensive war for national survival, the Talmudic sages would never have countenanced the reckless disregard for life that we are seeing now from those seeking to open their economies without providing sufficient safeguards to protect the most vulnerable.

We desperately need a functioning economy, but that is precisely why we need to have massive testing, tracing and a 14-day “downward curve” to enable a sensible opening while preventing needless deaths.

With the current situation becoming increasingly painful, both medically and economically, governments are coming up with their own calculations as to what a human life is worth as a means of helping them make excruciating policy decisions. A recent article in The New York Times states that the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission uses a figure of $8.7 million, the Environmental Protection Agency uses $7.4 million, and the Department of Transportation (which includes the Federal Aviation Administration ) uses $9.6 million.

Such calculations may be practical and in some manner necessary, but quantifying the value of a human life carries great risk and should be done with caution.

As the world commemorates this month the 75 anniversary of the end of the Second World War, let’s recall that the Nazis, who loved to put numbers on everything from death camp ledgers to human arms, put an actual value on a person’s life. In stark contrast, the idea that each human life is of infinite worth has been at the core of Judaism — and other traditions — for many centuries.

In his essay, ” Clouds of Smoke, Pillars of Fire,” Rabbi Irving (Yitz) Greenberg, one of the leading theologians of the post-Holocaust era, asserts that in contrast to the ethos that has defined Jewish values for centuries, the Nazis’ behavior proclaimed the fact that they thought that a Jewish life was not worth one cent.

This is what he means. When the Nazis struggled mightily to finish their genocidal mission in 1944 by wiping out nearly a million Hungarian Jews, they began to run short of Zyklon B, the lethal chemical of choice for their gas chambers. In addition, the Nazis deemed the costs excessive. So, to keep up with their diabolical quotas, they cut the gas in half, from 12 boxes to six per gassing, which in turn tripled the amount of time it took for the victims to die, increasing their suffering exponentially.

Even worse, according to testimony of survivors, some children were thrown while still alive straight into the furnaces. All to stretch their Deutschmarks and save gas. The result was a bottom line of less than one cent per Jewish corpse.

Greenberg did the math (and if you need proof, the original invoice for Zyklon B can be found in the Yad Vashem archives):

How much did it cost to kill a person? The Nazi killing machine was orderly and kept records. The bills for Zyklon B came to 195 kilograms for 975 marks, which equals 5 marks per kilogram. Approximately 5.5 kilograms were used on every chamber load, about 1500 people. This meant 27.5 marks per 1500 people. With the mark equal to $0.25, this yields $6.75 per 1500 people or 45 hundredths of a cent per person. In the summer of 1944, a Jewish child’s life was not worth the 2/5 of a cent it would have cost to put it to death rather than burn it alive.

Because life has infinite value, the greatest mitzvah (Jewish religious obligation) is to save a single life — so great that it supersedes the observance of nearly every other commandment, including Shabbat and the Yom Kippur fast. This understanding led to an extraordinary gesture last week, when 35 rabbis from Missouri put their names to a petition stating that voting by mail during a pandemic is a religious imperative. When lives are legitimately at risk, they are saying, the Torah obligates us to stay home.

Political theorist Judith Butler, whose recent work has focused on philosophies of vulnerability and mourning, claims that “learning to mourn mass death means marking the loss of someone whose name you do not know, whose language you may not speak, who lives at an unbridgeable distance from where you live.”

We have to learn how to mourn each single victim, so that instinctively, the soon-to-be hundred thousandth American to die of the coronavirus will be perceived as a unique, immeasurable universe, and not as a number.

A pastor in Greenwich, Connecticut, is memorializing each victim in his state by planting a flag on the front lawn of the church. We need to do that, too. We need our own Paper Clips Project — a memorial like the one a small rural school in Tennessee came up with, collecting six million paper clips to demonstrate the magnitude of the tragedy that was the Holocaust. We could stack our clips next to one of those omnipresent Johns Hopkins Covid-19 maps.

This is the scene on the front lawn of the First Congregational Church in Old Greenwich, Connecticut. Pastor Patrick Collins has a white flag for every Covid-19 victim in the state. pic.twitter.com/dGHWvshQQE — Paul P. Murphy (@murphy) May 1, 2020

These dead, these victims, helpless and vulnerable, the weakest of our society, whose lives have been cut short so painfully and in many cases so needlessly, must never be allowed to amalgamate into a nameless, faceless mass.

At the same time, the living, too — the unemployed, displaced and otherwise upended — need to be seen as individual sufferers rather than trends. At a time when our senses are overwhelmed by unimaginable numbers, no human being should become a statistic.

As the Holocaust begins to recede from immediate memory with the passing of 75 years, one incontrovertible fact shines like a beacon from out of the deepest darkness of the 20 century and stands as a sharp reminder to all of us as we face this overwhelming, numbing pandemic that will define the 21:

We must treasure each precious, priceless human life.