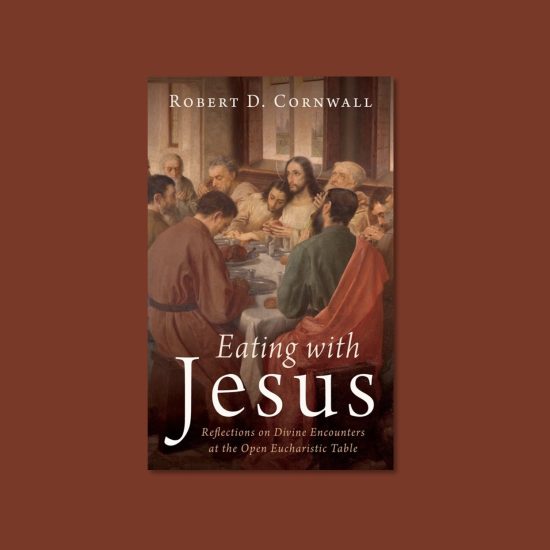

In this Sunday, May 24, 2020, photo, a Greek Orthodox priest distributes Holy Communion during Sunday Mass at a church, in the northern city of Thessaloniki, Greece, using a traditional shared spoon. (AP Photo/Giannis Papanikos)

ATHENS, Greece (AP) — One by one, the children and adults line up for the centuries-old ritual of Holy Communion, trying to keep a proper social distance. The priest dips a spoon into the chalice of bread and wine, which the faithful believe is the body and blood of Christ, and puts it into the mouth of the first person in line.

Then, with a move that would alarm an epidemiologist, he dips the spoon back into the chalice and then into the next person’s mouth.

Again and again, through the entire congregation.

Contrary to what science says, the Greek Orthodox Church insists it is impossible for any disease — including the coronavirus — to be transmitted through Communion.

“In the holy chalice, it isn’t bread and wine. It is the body and blood of Christ,” said the Rev. Georgios Milkas, a theologian in the northern city of Thessaloniki. “And there is not a shred of suspicion of transmitting this virus, this disease, as in the holy chalice there is the Son and the Word of God.”

This is proven, he said, through “the experience of centuries.”

Scientists warn that shared utensils can spread the coronavirus, and they also point to outbreaks linked to religious services around the world.

A communal spoon presents “fairly significant dangers,” said Dr. Nathalie MacDermott, an academic clinical lecturer for Britain’s National Institute for Health Research at King’s College London.

“The danger of transmitting any kind of respiratory viral pathogen or even bacterial infections is quite high with the sharing of utensils,” she said. “And for it to be passed among what is probably a relatively large group of people means that all it would take is one person to have coronavirus at the back of their throat, which potentially is in their saliva as well.”

In this Sunday, May 24, 2020, photo, a woman kisses an icon as she attends Sunday Mass outside a Greek Orthodox church in the northern city of Thessaloniki, Greece. Priests at the church still use a traditional shared spoon to distribute Holy Communion. Contrary to science, church officials say it is impossible for any disease, including the coronavirus, to be transmitted through Holy Communion. (AP Photo/Giannis Papanikos)

The Holy Synod, the church’s governing body, says any suggestion that illness or disease could be transmitted by Holy Communion is blasphemy, a stance echoed by the Church of Cyprus.

“Regarding the issue that is unjustifiably raised from time to time about the supposed dangers, which in these blasphemous views are said to lurk in the life-giving Mystery of Holy Communion, the Holy Synod of the Church of Greece expresses its bitterness, deep sorrow and diametrical opposition,” it said in a May 13 circular on social distancing measures in churches.

The Synod “underlines one more time to all those who, either due to ignorance or conscious faithlessness, brutally insult all that is holy and sacred, the dogmas and the sacred rules of our faith, that Holy Communion is ‘the medicine of immortality, antidote to not dying, but to living according to the teachings of Jesus Christ forever.’”

Whether Holy Communion should be changed or suspended for health reasons has become a hot button issue across much of the Christian Orthodox world, with churches generally refusing to bow to pressure from governments and scientists.

The church in the U.S. is taking a more pragmatic approach, allowing the use of individual spoons.

“The issue of a single Communion spoon poses a very simple question: What is more important, the Body and Blood of our Lord Jesus Christ, or the method by which we receive them?” Archbishop Elpidophoros, head of the Archdiocese of America, told The Associated Press. “The answer is just as simple; it’s not the method; it’s the Divine Communion itself.”

Elpidophoros said some have felt uncomfortable sharing a spoon during the pandemic.

“Why should these people, whose anxiety is real, be deprived of Communion?” he said. “That is precisely why I decided, after much consultation, that parishes may offer Holy Communion for every parishioner using multiple spoons that are not shared.”

Concessions also were made in Russia. In mid-March, the Russian Orthodox Church released instructions on adjusting the sacrament during the pandemic. Priests were told to wear gloves when handing out the bread, to disinfect the spoon and to use disposable cups for the wine.

In Ethiopia, which has the largest Orthodox Christian flock outside Europe, the ritual is unchanged, as it is in the Georgian Orthodox Church.

In response to public pressure against using a common spoon, the Georgian church noted the tradition is thousands of years old.

“Throughout these years, there have been many cases of life-threatening infections, during which Orthodox believers did not fear but strived even harder to get Communion through a common chalice and a common spoon,” it said in a statement.

In Greece, a firebrand priest, former Metropolitan Ambrosios, said he had excommunicated the education minister, prime minister and the civil protection deputy minister — the first for suggesting the coronavirus could be transmitted through saliva during Holy Communion, and the other two for closing churches during the lockdown. The Holy Synod, however, said only it had the authority to excommunicate.

Greece imposed a lockdown early on, a move credited with curbing infections. The country has reported 175 deaths and just over 2,900 confirmed cases.

But many of the faithful chafed under the lockdown that closed places of worship for all religions for about two months. It ran through Easter, the most important religious holiday for Orthodox Christians, and the inability to attend services weighed heavily on many.

When the ban was lifted May 17, thousands flocked to church.

“The issue of Holy Communion in particular is the only red line of the church and of the faithful in our souls,” said 19-year-old Michalis Gkolemis, attending services in Thessaloniki. “We don’t say that Holy Communion is the cure for all diseases, from the flu, for example, but we say that you cannot get sick by receiving Communion. You can’t catch a virus, something which isn’t proven scientifically but exists through experience.”

After ordering churches closed, the government has been more circumspect and has avoided the sensitive issue of Communion. The limited spread of the virus also has reduced the risk of a renewed outbreak, at least for now.

For scientists, concern is tempered by knowing that opposing the powerful Orthodox Church, into which most Greeks are baptized, could be counterproductive.

“This is a matter of public health concern,” said Dr. Gkikas Magiorkinis, assistant professor of hygiene and epidemiology at the University of Athens. “As an epidemiologist, I would like to be able to reduce the risk of transmission.”

But changing the minds of the faithful is “very difficult,” he said. “It’s a matter that can only be solved through discussion, and theological discussion rather than scientific discussion. Scientific discussion never helped, and it might have even worse results.”

Discussions with the church were always open, said Magiorkinis, who also advises the government on the virus.

“Only the church can provide a solution,” he said.

Kantouris reported from Thessaloniki. Associated Press writers Daria Litvinova in Moscow; Elias Meseret in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; Sophiko Megrelidze in Tiblisi, Georgia; and Menelaos Hadjicostis in Nicosia, Cyprus, contributed.