Image by Scott Younkin from Pixabay / Thomas Le, Unsplash

(THE CONVERSATION) The highest court in the land has given states some leeway in determining when and how to safely reopen places of worship during the COVID-19 pandemic. The move lends support to state officials making science-informed decisions that may inhibit church congregants from fully engaging in their faith.

In a 5-4 ruling issued close to midnight on Friday, May 29, the U.S. Supreme Court decided not to disturb the California governor’s order restricting religious service gatherings as part of its emergency pandemic response effort.

The decision is the latest turn in the debate over what places of worship may do during the lockdown and as the U.S. comes out of it. During the pandemic there have been frequent clashes as federal, state and local officials try to balance protecting the public’s health with the rights of individuals and groups to gather and practice their faith.

This is nothing new. I study public health law, ethics and policy, and I have seen how issues from vaccination exemptions to responding to the opioid crisis are steeped in such concerns.

Clashing over churches

The debate over church attendance began as soon the current crisis took hold and communities began to lockdown.

One of the earliest high-profile clashes involved the arrest and jailing of a Tampa Bay, Florida-area pastor. Pastor Rodney Howard-Browne, a controversial figure who has dismissed coroanvirus as a “phantom plague” held two large services in defiance of the county’s stay-at-home order and at a time when local COVID-19 cases were soaring. He was detained on May 30. But just two days after the arrest, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis issued an executive order declaring that “attending religious services conducted in churches, synagogues and houses of worship” were to be protected as “essential activities.” He added that the state order would override any contradictory local restrictions.

By that time, President Trump had already declared that Easter would be a “beautiful time” for the U.S. economy to be reopened – a goal that put him at odds with the science and some state governors. That plan was later abandoned.

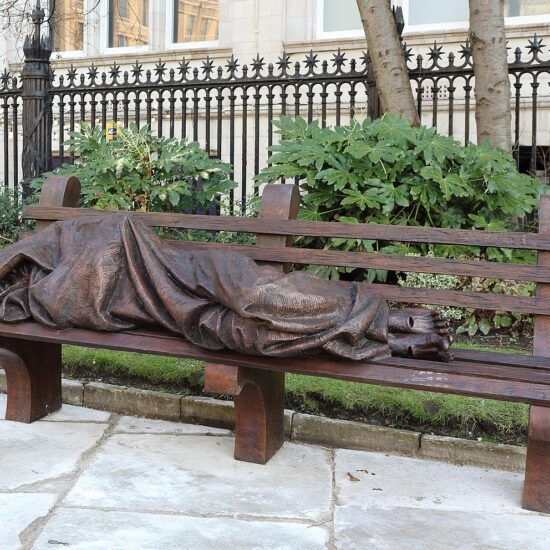

More recently, Trump described houses of worship as “essential places that provide essential services.”

But this characterization of live, in-person church services as “essential” blurs the distinct way that term was originally applied to businesses, services and employees in the crisis. “Essential” in this context referred to critical contributors to our nation’s infrastructure and workforce. They are the people involved with keeping our hospitals, food supplies, transport and utilities running, as well as law enforcement and our national defense.

But the president and many states are applying the term “essential” more broadly, as a way to signal certain values.

This is especially true when examining the mix of states’ approaches to in-person church gatherings.

States and SCOTUS

By late May, even the states hit hardest by the virus had begun to loosen their restrictions on gatherings. But when the first “stay-at-home” orders were issued, California was just one of nine states to ban live religious gatherings altogether. Meanwhile, around 20 other states initially limited live gatherings to 10 people or less. Doing so placed restrictions on church services akin to those on concerts, movie theaters or sporting events.

But other states followed a similar approach to Florida, labeling religious gatherings as “essential,” or at least declaring that they should be exempt from restrictions in place for other types of gatherings.

Indiana and Kansas both initially tried a political and scientific middle ground: characterizing church gatherings as “essential,” but still requiring that religious organizations follow the rules set out by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for in-person social gatherings, minimizing and discouraging live meetings until the public health threat was reduced.

From a public health perspective, restricting in-person religious gatherings makes sense. COVID-19 is most easily spread as an aerosol, such as when people are talking or singing. The risk of spread is also higher in closed spaces when in close proximity to someone infected and increases the longer you are near them.

Church-related gatherings often have all these features, and have been the nexus for many cases where COVID-19 has spread across a community.

Interestingly, the Trump administration eliminated warnings about church choir activities from the CDC’s latest guidance on safely reopening places of worship.

A graphic about the choir practice that resulted in a COVID-19 outbreak in Skagit County, Washington, in March. Courtesy of the CDC

Defiant churches tried different tactics to remain open. Some simply ignored the restrictions and continued to hold services. And California isn’t the only state to see state rules challenged in court. Kansas, Kentucky, Mississippi, New Mexico, Texas and Virginia have all seen similar legal action.

In many cases, the organizations fighting restrictions have cited the First Amendment and argued that it is unconstitutional to restrict church gatherings, especially when other secular so-called “essential” or “life-sustaining” entities – such as grocery stores, liquor stores and laundromats – are allowed to stay open. This line of argument was echoed in the Supreme Court decision’s dissenting opinion written by Justice Brent Kavanaugh in the Supreme Court case.

The Supreme Court, looking at the latest version of California’s restrictions – which limits churches to 25% capacity, or a maximum of 100 attendees – declined to second guess the state’s elected officials in their assessment of the best way to protect the public’s health. In his concurring opinion, Chief Justice John Roberts, the pivotal vote in the church case, seemed swayed by how officials endeavored to follow the science during a time “fraught with medical and scientific uncertainties.” He noted that religious services were more like social gatherings than “grocery stores, banks, and laundromats, in which people neither congregate in large groups nor remain in close proximity for extended periods.”

Good-faith efforts

The loosening of formal in-person gathering restrictions is beginning to take place across the country. This will likely make monitoring the rules more difficult and could result in greater reliance upon the vigilance of religious leaders, their congregants and perhaps guidance from the churches’ risk-averse liability insurance companies. For now, most churches and other religious entities appear to be remaining careful amid concern over the still present risks. Some are not.

But should infection numbers spike in the near future, state officials have the knowledge that a majority on the Supreme Court – for now at least – appear willing to follow the science and support their good-faith efforts to manage public health emergencies.

The Conversation is an independent and nonprofit source of news, analysis, and commentary from academic experts.