(RNS) — Measuring people’s true attitudes toward racial issues on surveys has long been one of the most difficult problems that social scientists face. However, in the last few decades scholars have developed methods that have helped us make progress in understanding the subtle ways that racist views not only persist but bubble to the surface in American society.

One of those has become known among researchers as racial resentment. Usually posed as a set of four questions, the racial resentment series presents the following statements — which some of us might recognize from discussions over the Thanksgiving table — and asks for respondents’ reactions, ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”:

1. Irish, Italians, Jews and many other minorities overcame prejudice and worked their way up. Blacks should do the same without any special favors.

2. It’s really a matter of some people not trying hard enough; if blacks would only try harder they could be just as well off as whites.

3. Over the past few years, blacks have gotten less than they deserve.

4. Generations of slavery and discrimination have created conditions that make it difficult for blacks to work their way out of the lower class.

Agreeing with statements 1 and 2 earns a respondent 1 point each. Disagreeing with statements 3 and 4 gains them another 1 point each. When added together it creates an index of resentment running from zero (no resentment) to 4.

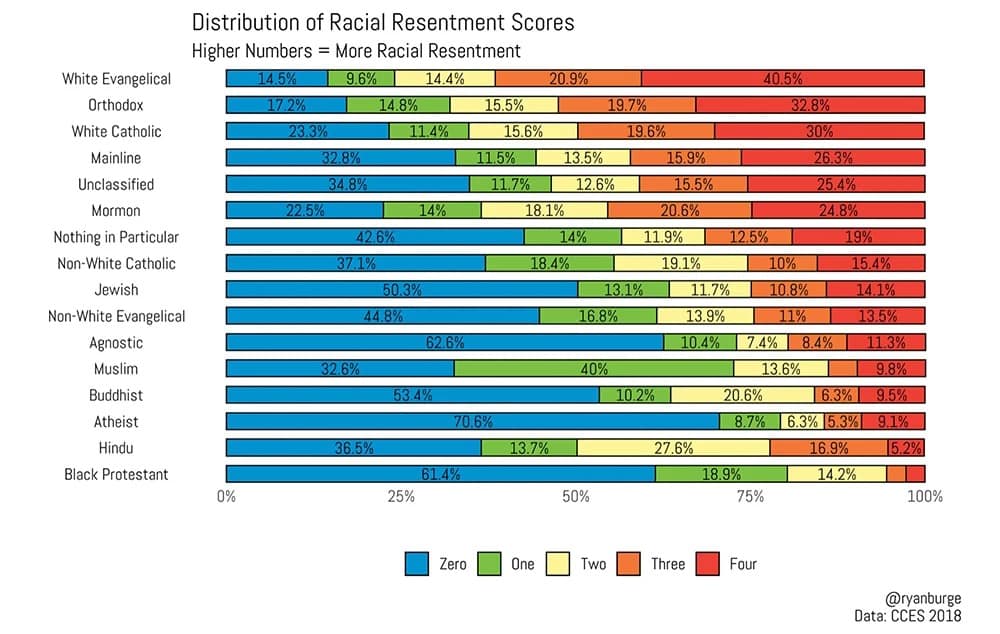

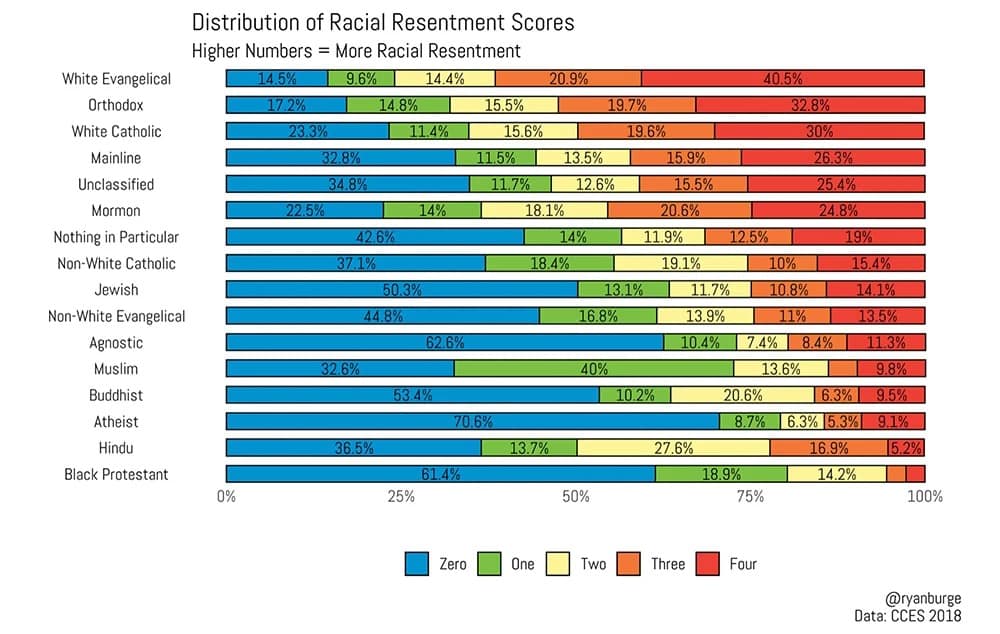

“Distribution of Racial Resentment Scores” Graphic by Ryan Burge

Using this method, a survey taken in November 2018 showed that the distribution of racial resentment across American religious traditions varies widely. Unsurprisingly, perhaps, those who belong to historically black denominations scored lower than those that were predominantly white. Buddhists and Jews were the only nonblack faith group for whom a majority of adherents had scores of zero.

But more than 60% of white evangelical Christians scored a 3 or 4 on the scale, as did half of white Catholics.

One significant outlier was atheists: Despite the fact that three-quarters of nonbelievers are white, 70.6% of them scored a zero on the scale.

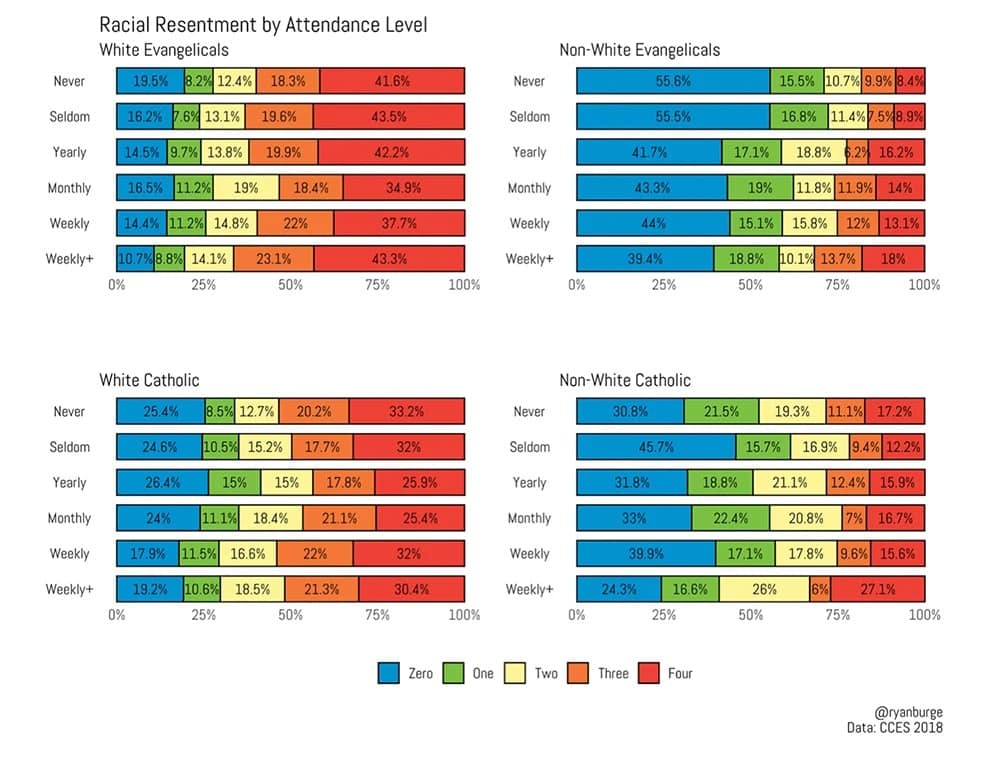

Breaking the sample down by worship attendance reveals some noteworthy patterns. Two in three white evangelicals who attend church more than once a week scored a 3 or higher on racial resentment. For white Catholics who attend as frequently, just over half scored 3 or higher.

Church attendance works in the opposite direction among nonwhite evangelicals and Catholics, who are twice as likely to score a zero as they are to score a 4 if they attend more than once a week.

“Racial Resentment by Attendance Level” Graphic by Ryan Burge

Certainly many white evangelicals also hold anti-racist views — more than 14% of those surveyed scored zero on the racial resentment survey. But overall the numbers run counter to the race “blindness” many white evangelicals have been arguing for in the face of the recent upheaval over race in our country.

Those attitudes may well be changing rapidly: Even 18 months ago, it may have been easier to ignore the institutional racism that exists all across the United States. A news story about police beating a black man could be written off as an aberration or an isolated incident. It’s becoming harder to hold that position now.

Still, if there’s a growing mountain of evidence that indicates that African Americans are treated much differently by the police, the courts and the school system, those who score high on racial resentment appear willing to ignore the plain facts.

Perhaps, too, many have simply been unaware. If so, it’s time for clergy to walk to their pulpits and speak truth to their congregations, though many will not want to hear it.