(RNS) — C.T. Vivian, a minister and advocate for civil rights who worked with fellow Baptist minister Martin Luther King Jr., died Friday (July 17) in Atlanta. Cordy Tindell “C.T.” Vivian was 95.

His daughter, Denise Morse, confirmed his death, describing him to Atlanta TV station 11Alive as “one of the most wonderful men who ever walked the earth.” He died of natural causes, business partner and friend Don Rivers told the Associated Press.

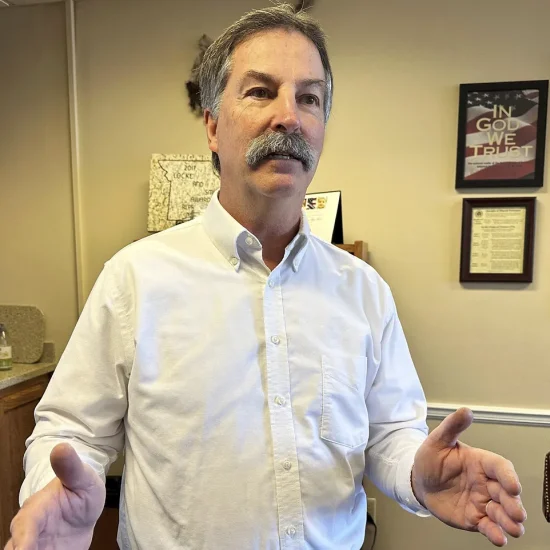

C.T. Vivian in Washington on Aug. 23, 2013. (Adelle M. Banks/Religion News Service)

Vivian’s social justice work preceded King’s, as the Boonville, Missouri, native nonviolently and successfully protested segregated lunch counters in Peoria, Illinois, in 1947. He later became part of King’s executive staff at the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in Atlanta. Late in life, Vivian continued to contribute to the civil rights cause, serving in his late 80s as the president of the SCLC.

In between his times at that civil rights organization, Vivian was active on issues of equality for decades, on the ground in marches and in lecture halls teaching about democracy and racial justice. Vivian was honored in 2013 at age 89 with the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

“The Rev. C.T. Vivian was a stalwart activist on the march toward racial equality,’’ says the White House citation read before President Barack Obama bestowed the medal on Vivian. “Whether at a lunch counter, on a Freedom Ride, or behind the bars of a prison cell, he was unafraid to take bold action in the face of fierce resistance.”

In a 2013 interview with Religion News Service, Vivian said he had collected “stacks” of awards over the years, but he hoped the medal would help draw attention to the causes to which he devoted his life.

“People will listen that wouldn’t otherwise listen and that’s what’s important,” he said. “If it doesn’t help you help somebody, then it might as well not be there.”

His death was noted by clergy, scholars, and organizations that shared his concern for civil rights.

“Whenever I spent time with C.T. Vivian, I sensed that I was walking with a man who walked with God,” tweeted Raphael Warnock, senior pastor of Atlanta’s Ebenezer Baptist Church, where King once served as a co-pastor. “He was not anxious or afraid. This morning he winked at death while his smiling face touched the face of God. Well done, servant, well done.”

The Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change tweeted about Vivian’s “sacrificial” life.

“A powerfully well-lived life that lifted humanity,” it said. “We will miss you. Thank you, sir.”

Over the course of his life, Vivian held numerous roles — pastor, editor for the Sunday School Publishing House of the National Baptist Convention USA, and dean of divinity at Shaw University Seminary in Raleigh, North Carolina.

But he gained global attention with news coverage in 1965, when he confronted Sheriff Jim Clark on the steps of a Selma, Alabama, courthouse as civil rights activists attempted to register to vote. As Vivian stood almost nose to nose with the sheriff, Clark turned his back on him.

“You can turn your back on me but you cannot turn your back upon the idea of justice,” Vivian told Clark. “You can turn your back now and you can keep the club in your hand but you cannot beat down justice. And we will register to vote because as citizens of these United States we have the right to do it.”

Within minutes, Clark punched the minister in the face, knocking him down the steps and leaving his face bloody.

“Many people did not have that kind of courage,” Gerald Durley, pastor emeritus of Providence Missionary Baptist Church in Atlanta, where Vivian worshiped, told RNS in 2013. “There were many with courage, but not the kind of courage that C.T Vivian demonstrated.”

President Barack Obama places the Presidential Medal of Freedom on C.T. Vivian in the East Room of the White House on Nov. 20, 2013. (Adelle M. Banks/Religion News Service)

Almost 50 years after the Selma confrontation, as he received the presidential recognition, Vivian was still hard at work. He was the board chairman of a minority-owned bank with branches in eight locations in Georgia, and he was the director of the Urban Theological Institute at Atlanta’s Interdenominational Theological Center, a consortium of African-American seminaries. He also was fostering career development and innovative leadership for at-risk youth and college students through his C.T. Vivian Leadership Institute.

At the time of his presidential honor, Vivian viewed the award as a recognition of his life’s work.

“It’s like the laying on of hands,” he told RNS, “when the nation says that you have served well.”