(RNS) — The first of Frederick Douglass’s three autobiographies, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave, gained a wide American and trans-Atlantic audience when it was published in 1845, and served as a spark to the growing abolitionist movement and to Douglass’s prominence as a leader.

But one aspect of the work has not received the treatment it deserves. Tucked into the back of the book is an appendix that contains a scathing description of his experience of American Christianity:

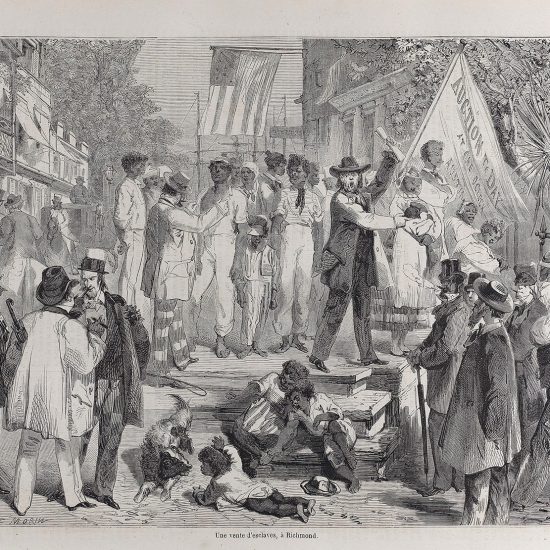

The slave prison and the church stand near each other. The clanking of fetters and the rattling of chains in the prison, and the pious psalm and solemn prayer in the church, may be heard at the same time. The dealers in the bodies and souls of men erect their stand in the presence of the pulpit, and they mutually help each other. The dealer gives his blood-stained gold to support the pulpit, and the pulpit, in return, covers his infernal business with the garb of Christianity. Here we have religion and robbery the allies of each other — devils dressed in angels’ robes, and hell presenting the semblance of paradise.

In its 2018 American Values Survey, PRRI, the research firm that I lead, confirmed a disturbing pattern: While the overt connections between slavery and Christianity have long since been abandoned, the connections between White supremacy and Christianity continue to exist today. Not only among White evangelicals in the South but among White mainline Protestants in the Midwest and White Catholics in the Northeast, survey after survey shows that holding more racist attitudes is independently associated with a higher probability of identifying as a White Christian; and conversely, adding Christianity to the average White person’s identity moves him or her toward more, not less, affinity for White supremacy.

White supremacy lives on today not just in explicitly or consciously held attitudes among White Christians; it has become, down through the generations, deeply integrated into the cultural DNA of White Christianity itself.

That last statement, standing alone, sounds shocking. But an honest look at the historical arc of White Christianity in America suggests that we should be astonished if it were otherwise. For centuries, through Colonial America and into the latter part of the 20th century, White Christians literally built — architecturally, culturally, and theologically — a version of Christianity that held an a priori commitment to White supremacy.

An art installation of slaves at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice by artist Kwame Akoto-Bamfo in Montgomery, Alabama. (Adelle M. Banks/Religion News Service)

At key potential turning point moments — slavery, Reconstruction, Jim Crow laws, the civil rights movement, and the policing and criminal justice crisis among African Americans — White Christians, for the most part, did not just fail to evict this sinister presence, they continued to aid and abet it.

As the country is once again facing a reckoning on racial justice, perhaps the biggest obstacle to White Christians’ full participation in the movement for racial equality is an unshakable commitment to our own innocence. As I conducted the research for my new book, White Too Long: The Legacy of White Supremacy in American Christianity, I came to the conclusion that White Christians must find the courage to begin a long journey that starts with the simple act of telling the truth.

In religious terms, it means giving an unflinching testimony about ourselves, about our history and about how a commitment to White supremacy — both past and present, conscious and unconscious — has disfigured our faith.

This journey of confession and self-realization isn’t a simple one, but it begins with bearing witness to a more complete, and truer, story. Here’s what the beginning of mine looks like.

In my house I have a family Bible that belonged to my fifth great-grandfather on my mother’s side, printed in 1815. On the front inside cover it is inscribed, “Presented by Nathaniel Ellis to his friend Pleasant Moon, July 17th, 1825.”

Pleasant Moon was among the first generation of my mother’s family to be born in Georgia, where five generations of my family have lived in either Twiggs County or Bibb County. Pleasant’s father, William H. Moon, my sixth great-grandfather, had been born in 1740 in Albemarle County, Virginia, and served in the Revolutionary army. Sometime after 1790, he moved his family to the Georgia frontier, on land that was being seized by the Georgia government from its Indigenous inhabitants, the Creek and Cherokee Indians, and distributed via rolling lotteries to white settlers.

Although I have not been able to locate a will for my fifth great-grandfather, I’ve been able to locate one for his father’s brother and namesake, Pleasant Moon Sr. At his death in 1818, the county recorded both his will and an “Inventory of the Goods and Chattles [sic] of Pleasant Moon, Deceased.” The inventory was thorough, including items like “1 young bay mare @ $60;” “1 feather bed and furniture @ $90;” and “1 shot gun @ $11.” Not counting the land, my sixth great-uncle’s estate was fairly modest, totaling $2,293.22, or approximately $46,000 in 2019 dollars.

Most shocking, though, were two listings near the top of the household inventory: “1 negro woman named Naomi @ $800, & 1 named Susan @ $450,” totaling $1,250; and on the line below that, “1 named Eliza at $275, & 1 named Bird, a boy @ $150,” totaling $425. To put this into perspective, there is no other single line in the entire page-long household inventory that registers more than $100. Taken together, these two lines of human slave property totaled $1,675, accounting for an astonishing 73% of the assets of the estate.

In other words, even among my barely-above-subsistence-farming ancestors, their way of life and economic well-being were thoroughly dependent on owning slaves.

With the exception of the few preschool years in Wichita Falls, Texas, I have never lived in a county that is free from a history of lynching. The place in which I spent most of my formative years, from the time I was 7 to 21, particularly stands out. At 22 lynchings, Hinds County, Mississippi, is the county with the fourth-highest number of lynchings in the state and is tied for 15th as the county with the most lynchings nationwide.

Even this awful tally understates the case. My home state, which lauds itself as “the hospitality state,” contains such a density of counties with legacies of lynching that they drive the total to 654, giving Mississippi the dishonor of having the highest number of recorded lynchings of any state.

But this legacy of White supremacy in my life was not all in the distant past. My high school and college experiences reenacted the history of White oppression of both African Americans and Native Americans. In my hometown of Jackson, Mississippi, my public, integrated high school’s nickname was the Rebels, and the band played “Dixie” as a cheerleader ran down the sidelines with a large Confederate battle flag each time our football team scored a touchdown.

My college experience wasn’t much better. My Southern Baptist-affiliated school, Mississippi College, were the Choctaws. To rouse the crowd at sporting events, the band played stereotyped, minor-key music (think bad early westerns) while the crowds, including me, made an up-and-down tomahawk motion in unison with our right arms bent at the elbow, chanting, “Scalp ’em, Choctaws, scalp ’em!”

My story is unremarkable among my fellow White Christians. My ancestors weren’t large plantation owners, Confederate generals or, as far as I know, active members of the KKK. My ancestors were more carried along by the shapers of the great currents of history. Somehow I had a sense that this more modest history provided some inoculation against White supremacy’s potency.

As I’ve moved through the process of retelling my own story, however, I’ve been astonished at how ubiquitous the claims of White supremacy have been on my life. I grew up knowing that my parents had made a conscious decision to shield me and my siblings from the worst of the racism that was ubiquitous in our grandparents’ generation and before. But even with that protection, the ways in which White supremacy crept into my worldview, my faith and even my body are overwhelming.

I’d wager that many — maybe even most — White Christians, with little effort, could uncover a very similar narrative about their own family and experience, and the ways in which White supremacy, like kudzu, has crept its way forward through the family tree and into their churches.

The only way to save ourselves, and our country, from the stranglehold of this invasive parasite, is, at long last, to bear witness to the truth. Only then will we have the perspective to distinguish between it and the healthy branches straining under its weight. And even then, we will need to find the resolve not just to prune the parasite back for a season but finally to kill it, root to stem.

Robert P. Jones is the CEO and founder of PRRI. This article is adapted from “White Too Long: The Legacy of White Supremacy in American Christianity,” from Simon & Schuster