(RNS) — In case you hadn’t heard, last week President Donald Trump attacked his presumptive Democratic opponent, Joe Biden, on religious grounds. “No religion,” declared Trump. “No anything. Hurt the Bible. Hurt God. He’s against God.”

It’s been 220 years since the religion card was played so bigly in an American presidential campaign. The precedent is more apt than you might think.

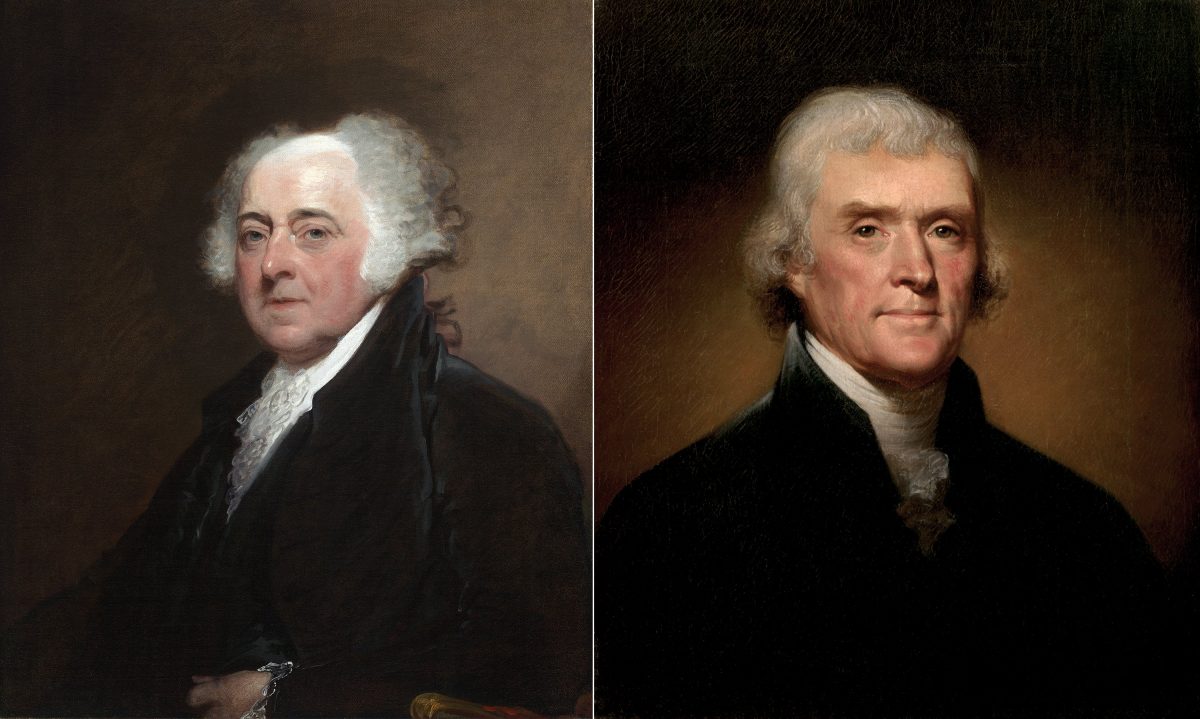

John Adams (left) and Thomas Jefferson.

The election of 1800 pitted the incumbent president, John Adams, against his old-friend-turned-bitter-rival Vice President Thomas Jefferson. In the two-party system that had emerged in the 1790s, Adams was the Federalist, Jefferson the Democratic-Republican. The Federalist case against Jefferson centered on charges that he was a “Jacobin,” a radical on the order of the French revolutionaries he had admired since serving as American ambassador to France in the late 1780s.

In a series of newspaper articles published in 1798, Alexander Hamilton attacked those revolutionaries for trying to “undermine the venerable pillars that support the edifice of civilized society,” not least by “the attempt … to destroy all religious opinion, and to pervert a whole people to Atheism.” Hamilton claimed that Jefferson was, like them, an atheist who, with the help of fellow American Jacobins, would pursue the same agenda if elected.

In the words of another Federalist writer, the choice was clear: “GOD — AND A RELIGIOUS PRESIDENT … JEFFERSON AND NO GOD.”

To be sure, Biden, the cradle Catholic who carries a rosary wherever he goes, is a far religious cry from Jefferson, the dyed-in-the-wool deist who created a cut-and-paste version of the Gospels with the supernatural material stripped out. But last week’s claim by Trump that Biden is “following the radical left agenda” harks back to the accusation that Jefferson was following the Jacobin playbook.

If Trump himself lacks the historical awareness to recognize this, his legal enabler, Attorney General Bill Barr, is on the case. Referring to Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the 18th-century philosopher whose ideas helped inspire the French Revolution, Barr informed Fox News host Mark Levin on Sunday (Aug. 9) that the Democrats have become the “Rousseau-ian Revolutionary Party that believes in tearing down the system.”

Like the Jacobins, the Dems have, in Barr’s view, replaced Christianity with their own infidel faith.

“It’s a secular religion,” he said. “It’s a substitute for religion. They view their political opponents as evil, because we stand in the way of their progressive utopia that they’re trying to reach.”

Of course, this characterization ignores the fact that the Democrats’ most loyal constituents, African Americans, happen to be among the most religious segments of American society. Similarly, Jefferson enjoyed the strong support of the country’s fast-growing evangelical population — the Baptists in particular.

Then as now, evangelicals were deeply concerned about religious liberty; but unlike now, for them that meant the greatest possible separation of church and state — a Jeffersonian position if ever there was one. With some justice, they regarded the Federalist campaign against Jefferson as an effort to establish a de facto religious test for federal office.

Unlike Trump, John Adams did not himself attack Jefferson for irreligion. And unlike Biden, who called Trump’s attack “shameful,” Jefferson did not publicly respond to the attacks. As he wrote to James Monroe, “As to the calumny of Atheism, I am so broken to calumnies of every kind … that I entirely disregard it.”

As for Alexander Hamilton, with Jefferson becoming president in 1802 he cooked up a plan to “combat our political foes” by creating “The Christian Constitutional Society.” It was to be a membership organization dedicated to supporting Christianity and the Constitution by disseminating federalist propaganda, supporting federalist philanthropic exercises and electing “fit men” to public office.

The following year, Hamilton was killed in his duel with Aaron Burr. But for that, Jerry Falwell Sr., Pat Robertson, Tony Perkins et al. might have had an organizational precedent to look back to.