NEW YORK (AP) — For Jimmy Gates Sr., the 2008 presidential election year was one to remember — and not just because it yielded a historic result as the nation elected its first Black president. The pastor of Zion Hill Baptist Church in Cleveland recalls how, on the last Sunday of early voting before the general election, he and his congregation traveled in a caravan of packed buses, vans and cars to the city’s Board of Elections office and joined a line of voters that seemed to stretch a mile.

“What a sight to see,” Gates said. “Seniors, middle-aged people, young people.”

In recent election cycles, Black church congregations across the country have launched get-out-the-vote campaigns commonly referred to as “souls to the polls.” To counteract racist voter suppression tactics that date back to the Jim Crow era, early voting in the Black community is stressed from pulpits nearly as much as it is by the candidates seeking their support.

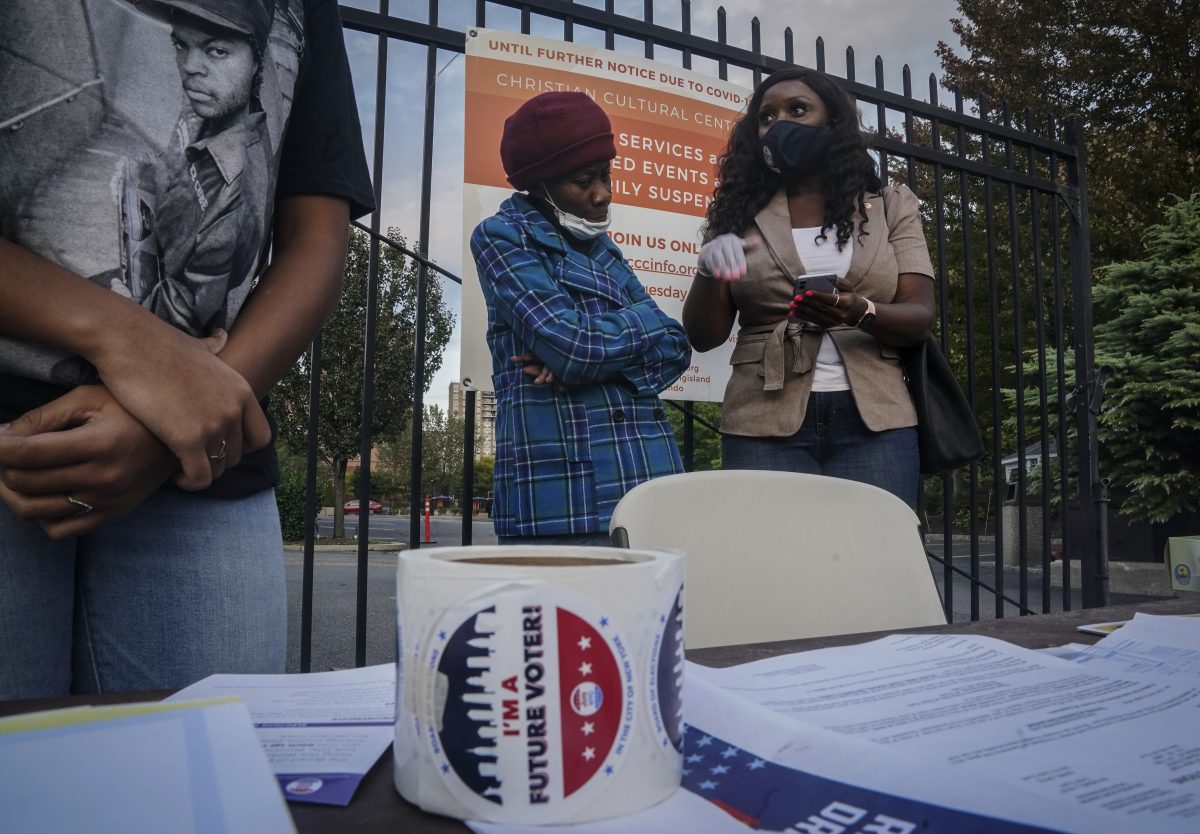

New York City Council member Farah Louis (right), who works as a volunteer with Christian Cultural Center’s Social Justice Initiative’s voter registration drive, tries to convince a woman to register at a table outside the the church on Oct. 1, 2020, in the Brooklyn borough of New York. (Bebeto Matthews/Associated Press)

But voter mobilization in Black church communities will look much different in 2020, due in large part to the coronavirus pandemic that has infected millions across the U.S. and has taken a disproportionate toll on Black America.

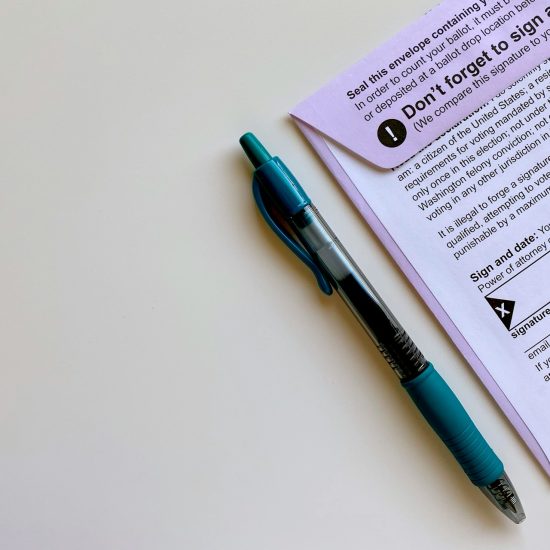

Churches have organized socially distant caravans with greatly reduced transportation capacity for early voting and Election Day ballot-casting. Church volunteers are phone-banking and canvasing the homes of their members to ensure mail-in and absentee ballots are requested and hand-delivered to election board offices or drop boxes before the deadlines.

But outreach has been complicated because many churches have been holding services virtually for months, with some having only recently resumed worship in-person. Black Voters Matter, a national voting rights group that organizes in 15 states, is trying to help churches assist people who count on a “souls to the polls” ride on or before Election Day.

“It’s not whether there are enough votes out there,” said Cliff Albright, a co-founder of the group. “It’s whether we have the strategy, the resources and the election protection to make sure that the voters who want to show up are actually able to do so and be counted.”

The Associated Press interviewed pastors, congregants and voting rights advocates nationwide to get a sense of how efforts to mobilize Black voters would play out during a deadly pandemic when Black people have been disproportionately affected by virus-related layoffs, and issues of systemic racism are top of mind.

Black Americans have far higher rates of joblessness than the national average and the highest COVID-19 mortality rate of any racial group. The turbulence of 2020 and fears of contracting the coronavirus have the potential to depress turnout even among reliable segments of Black voters, advocates say. So this year’s voter mobilization has to succeed at a level it didn’t in 2016, compared to 2008 and 2012, Gates said.

“We must vote like our life depends on it,” he said. “Yes, we know God takes care of us and is the supplier of all our needs. But God has given us a will to do the right thing. You didn’t listen to us in 2016. So my thing is, do you hear me now?”

Some pastors say the coast-to-coast unrest that followed the police killings of Black Americans this year have motivated their congregations. In Minneapolis, where a white officer held his knee to the neck of George Floyd, voters want to see policing reforms at the legislative level, said Bishop Divar L. Bryant Kemp, pastor of New Mount Calvary Baptist Church in North Minneapolis.

Bishop Divar L. Bryant Kemp poses at the New Mount Calvary Baptist Church food shelf on Oct. 1, 2020, in North Minneapolis. (Jim Mone/Associated Press)

“I tell people all the time, ‘Don’t talk to me about what needs to be changed if you haven’t voted to make a change,’” he said.

The challenge for Kemp will be getting voters to the polls safely. A church van used in previous elections recently broke down. Kemp also understands the pandemic risks all too well. He contracted COVID-19 in July and was hospitalized for five days, forcing him to stay away from his church for three weeks.

“We considered renting a van to take them to the polls, but either way we’re going to do it,” Kemp said.

“Souls to the polls” as an idea traces back to the civil rights movement. George Lee, a Black Mississippi entrepreneur, was assassinated by white supremacists in 1955, after he helped nearly 100 Black residents register to vote in the town of Belzoni. The cemetery where Lee is buried has served as a polling place.

“There was a statement that he once made advocating voting rights: ‘Don’t cry for my mama and my daddy. They’re already gone. You need to cry for your children that will come along,’” said Wardell Walton, Belzoni’s first Black mayor, who served between 2005 and 2013.

Lee’s memory should “inspire us to continue to move forward despite the obstacles,” said Walton, 70.

Across the U.S., early voting rules vary state-to-state, but begin for the vast majority of eligible voters in October at an average of 22 days before the election, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. Initial signs suggest Black voters are indeed intent on casting a ballot this year. Steady traffic at early voting sites in states like Ohio and strong returns of mailed-in ballots in North Carolina, Georgia, and elsewhere indicate an energized Black electorate.

Even without the hurdles of a pandemic, voter suppression is a persistent election year issue for Black Americans. The civil rights movement brought about passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which prohibited racial discrimination in voting. Despite the law, efforts to thwart voting for minorities have required constant vigilance. In some states, suppression worsened because of a 2013 Supreme Court ruling that gutted a section of the law requiring states with a history of racially discriminatory voting rules to get federal approval before changing election laws.

Ahead of the 2012 general election, Republican-controlled state legislatures and local elections officials put limits on early voting periods that “souls to the polls” campaigns rely on. Now, some Black Americans are wary of President Donald Trump’s false claims of widespread mail-in voter fraud, along with reported mail delivery problems within the U.S. Postal Service. Advocates have decried the president’s recent call for his most fervent supporters to monitor the polls on Election Day as an attempt at voter intimidation in the Black community, although Trump has denied this.

Jane Bonner, a 53-year-old health care administrator who attends church at Walk of Faith Cathedral in Austell, just west of Atlanta, said her 91-year-old parents can recall their own experiences with disenfranchisement. Her mother was denied voter registration when she could not tell the registrar “the number of days, hours and minutes until her next birthday,” she said.

“I’m now determined more than ever to go to the polls and cast my ballot in person, as opposed to by mail,” Bonner said.

Keith White, a director of social justice initiatives at Christian Cultural Center, has been petitioning New York City elections officials to allow his predominantly Black church in Brooklyn to serve as a polling location. Whether or not that happens, the church will use its van and a charter bus to shuttle early voters between now and Election Day, he said.

“People are concerned about this election and the implication that it might have for our children’s future,” White said. “Folks will be out early. I don’t think they will be waiting until the last day before Election Day.”