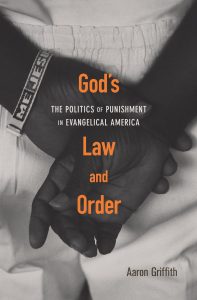

(RNS) — When it comes to mass incarceration, American evangelicals are complicated. So says Aaron Griffith in his new book, God’s Law and Order: The Politics of Punishment in Evangelical America.

On the one hand, evangelicals led the charge for greater law and order in the postwar era, with the National Association of Evangelicals favoring the death penalty and FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover penning regular columns in the pages of Christianity Today on combating lawlessness.

On the other hand, evangelicals saw crime as a missionary opportunity, launching innovative ministries to bring compassion and healing to prisoners across the country. Former Nixon aide Chuck Colson’s Prison Fellowship is perhaps the best-known example of evangelicals providing faith-based programming to those in prison and advocating for criminal justice reform legislation.

Aaron Griffith

Griffith has the background and education to tell this story. He grew up in an evangelical family, attended Wheaton College as an undergraduate, and worked in prison ministry while earning his doctorate from Duke Divinity School.

He begins his book by describing the rapturous response students at Wheaton gave to Burl Cain, warden of the Louisiana State Penitentiary, better known as Angola, who spoke at a chapel service there in 2005. Cain, a controversial figure, was known for his folksy mix of law-and-order toughness and a belief in the power of inmate rehabilitation through Jesus. That earned him wide admiration in evangelical circles where the two impulses — punishment and the possibility of redemption — defined the movement’s response to crime in the 20th century.

Griffith, who now teaches history at Sattler College, a small Christian liberal arts school in Boston, ends his book with another figure who spoke at Wheaton — Bryan Stevenson, the social justice lawyer who has worked to exonerate innocent prisoners on death row and eliminate excessive sentences.

Underlying it all, Griffith explores how evangelicals have overlooked systemic racial inequalities and disparities that drove their approach to crime and punishment.

RNS spoke to Griffith about his book, published by Harvard University Press. The interview was edited for length and clarity.

RNS spoke to Griffith about his book, published by Harvard University Press. The interview was edited for length and clarity.

What led you to write this book?

There are two reasons. As I was looking for a topic for my dissertation, I was reading all these wonderful texts on the history of American evangelicalism and the way evangelicals have become a political and cultural force, especially from the 1950s on. Often those works were focused on issues like the economy, sexuality, abortion, the Cold War, communism. Then I started digging into mass incarceration and why the U.S. has such an immense prison system and so many people behind bars. I started to wonder what these two realities — the surging influence of evangelicals in post-War America and the rise of mass incarceration — have to do with one another.

The other reason is more personal. I was trained in evangelical institutions. I saw first hand in my own experience in church and prison ministry how there was a need for a deeper, more critical look at why we do the things we do as it relates to criminal justice. Some of this was a result of seeing people I know who were incarcerated. I wanted to understand their stories.

You find a contradiction. Evangelicals don’t like big government. But they do want more prisons and government funding for law enforcement. How do you explain that?

As a student of evangelicalism, I’d been trained to think most evangelicals are suspicious of the state and want less government and more personal responsibility. But what I learned writing this book is how the profoundly large presence of our criminal justice system is a form of state power, and it’s a form liberals and conservatives see as a positive good. Evangelicals have a flexible conscience of being very anti-state when they need to be. But they can be supportive of the state’s use of force and violence when they want to be. We need a more expansive understanding of evangelicals in this way.

At the same time, some evangelicals develop a pretty profound critique of the justice system. This is what prison reformer Chuck Colson does. He approaches the problems in the prison system — overcrowding, horrific conditions, unfairness — and says this is a problem of big government. We need to get away from models of state control that emphasize rehabilitation and expand the government’s role and give power back to individuals. He represents how this mentality evolves. Even President Trump is a good example of this. He’s a law-and-order president but oversaw and championed criminal justice reform and passing the 2018 First Step Act.

Your book takes a critical look at Billy Graham and how he led the charge for law and order. Explain how he evolved on this.

There are two main features. So much of Graham’s early ministry in the late ‘40s and ‘50s draws on concerns about crime and juvenile delinquency. There are these youths terrorizing cities. Graham sees this as a way to bring home his message of sin and conversion. This is not law-and-order politicking. It’s crime as a religious problem. It can be solved if people come to Jesus. Criminal justice doesn’t get involved.

This changed for Graham in the 1960s. The perception of social unrest, protests in the midst of the civil rights movement and the uprisings in various cities — Watts (Los Angeles), Newark, Detroit. That unrest, which is highly racialized, makes him nervous. That’s where he starts to say there’s a need for law and order. He becomes much more comfortable with Richard Nixon. He is the leading evangelical example of this turn away from the gospel alone as the solution to social problems, to law and order as a way to keep disorder at bay. It’s the culmination of those two streams that result in the prison ministry surge of the 1970s.

Why is it so hard for evangelicals to see race as a systemic issue behind the rise of crime?

Evangelicals in the midst of the civil rights movement are sitting on the sidelines. There are lots of white moderate evangelicals who are sympathetic to the broader goals of racial equality but not a fan of protests, or what leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. are doing to change policy and confront Americans on this issue. It’s no accident that as debates about the civil rights movement are occurring, that’s where evangelicals’ conscience on criminal matters are being formed.

On the one hand, there’s a strong confidence in the law as a way to deal with unrest. But of course that unrest is happening primarily in African American neighborhoods and in response to police brutality. Those neighborhoods are a product of racist redlining practices and underinvestment by cities and states. They are themselves racial realities. Law and order becomes an easy way to not have to deal with these inequalities that are there. They can say, ‘After the civil rights movement, we’ve achieved equality, we’ve achieved integration. There shouldn’t be any more protests.’

The second part, and it surprised me in my research, is that so many evangelicals saw policing as a humanitarian intervention, as, in fact, a gift to Black neighborhoods — a way to reward the vast majority of law-abiding ‘good’ Black Americans. That’s a repeated refrain from the ’60s on. The problem, of course, is that there’s little awareness of the way police routinely operate in a way that’s harmful to Black neighborhoods. If you send a police presence into a neighborhood, more people will get arrested. So it’s those things working together. A confidence in the law that overrides awareness of systemic issues and a lack of awareness of how ramped-up law and order can go wrong.

You end your book with lawyer and social justice advocate Bryan Stevenson speaking to students at Wheaton College. Are evangelicals changing?

Yes, but I worry the change happening will repeat the problems of the past. There’s an increased recognition in the wake of the killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor and countless others that America has a problem. White evangelicals are aware of this, too. They know something is wrong.

But the moves many evangelicals are making are repeating the mistakes of the past. The answer for so many evangelicals is to double down on the idea that policing can be reformed and prisons made better. There is not an interrogation of the assumption that policing and prisons themselves are the problem. They are seen as reformable and redeemable.

Evangelicals aren’t alone in this. Joe Biden’s presidential platform says we can invest more in community policing and can have more training given to police departments so they can become more humane. This is where the story of evangelicals is also the story of America.

We are having a hard time imagining America can be different. But as long as Americans can’t imagine something else, we will continue to invest in trying to reform the system we have. That doesn’t mean things can’t get better within that system. But the fundamental inequalities will always remain.

This is where a lot of pastors are struggling to know how to talk about these kinds of issues. No one wants crime in their neighborhood. How do you then deal with public safety without immediately thinking of more policing as the option? It will require a larger reimagining of what our cities and neighborhoods look like and how we’ll deal with structural inequalities that are there. I have hope. I think it will be difficult, though.

Is there another Chuck Colson on the horizon — someone who can bring the discussion into the public consciousness?

There are people like Colson who are not as well-known in the public evangelical conscience, people like Pat Nolan who heads up conservative justice reform advocacy and, like Colson, was incarcerated and had a dramatic conversion experience. There’s Kanye West who went into a prison to host one of his concerts.

Bryan Stevenson is probably the closest thing we have, even though he’s not nearly as evangelical as Colson was. Stevenson has a much larger footprint. But his book ‘Just Mercy’ is clearly mobilizing Christian themes. He talks about the need to acknowledge and confess our American sins of racism as it relates to issues like criminal justice. I would see him as someone with a parallel public impact and is drawing on similar Christian concepts, but his ministry looks different than Colson’s.