ATLANTA (AP) — In 2008, when Barack Obama was under fire for a sermon his former pastor delivered years earlier, the aspiring president distanced himself from the preacher’s fiery words that channeled Black Americans’ anger over racism. But Rev. Raphael Warnock defended Jeremiah Wright.

“When preachers tell the truth, very often it makes people uncomfortable,” he said on Fox News.

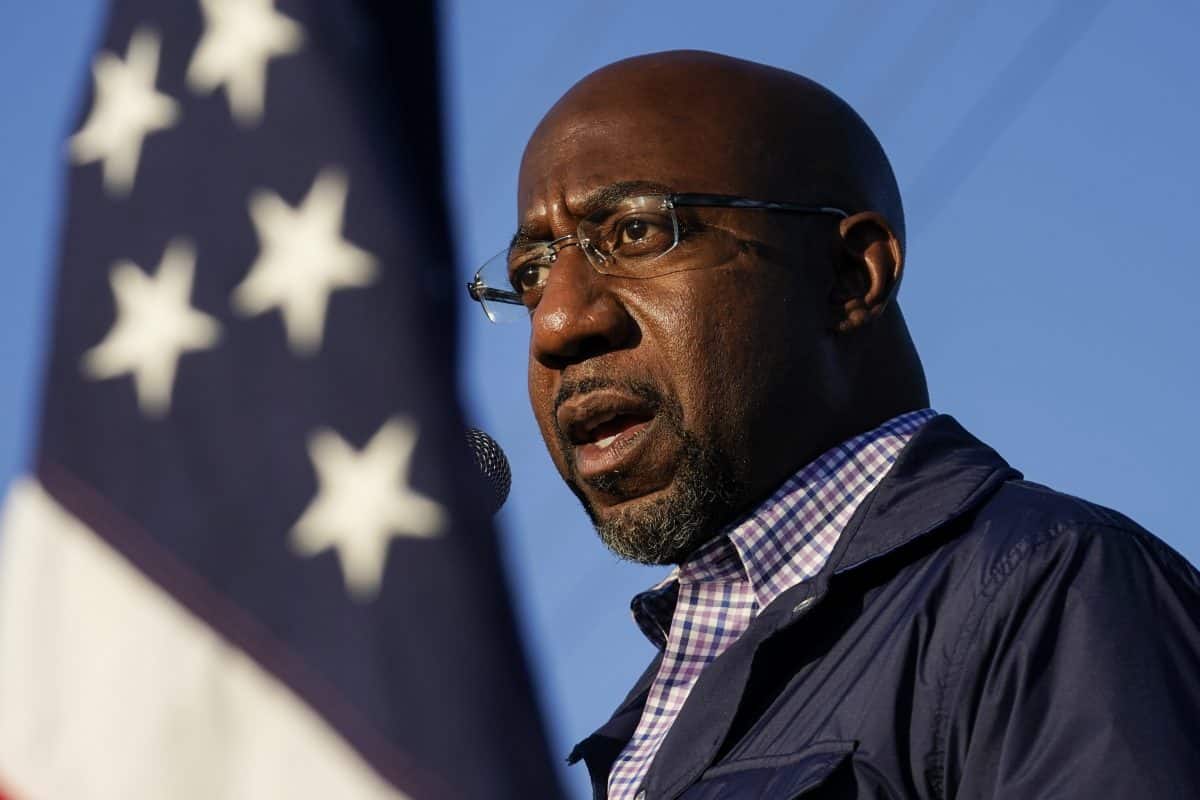

Raphael Warnock, speaks during a campaign rally in Marietta, Georgia, on Nov. 15, 2020. (Brynn Anderson/Associated Press)

Now Warnock is the politician running for office and the one under attack for his sometimes impassioned words from the pulpit. And once again, he is not backing down. Warnock, 51, says his run for U.S. Senate in Georgia — one of two races on Jan. 5 that will determine control of the Senate — is an extension of his years of progressive activism as head of the church where the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. preached.

Warnock is calling for bail reform and an end to mass incarceration; a living wage and job training for a green economy; expanded access to voting and health care, and student loan forgiveness. It’s an unabashedly liberal platform that may galvanize the Democrats he needs to turn out to vote in the runoff election.

But it also carries risks. His opponent, Republican Sen. Kelly Loeffler, has blasted his rhetoric and proposals as “radical,” socialist, and out of step with Georgia residents. Georgia voters are also likely to hear more about that from President Donald Trump, who announced Saturday that he will return to the state on Jan. 4, the eve of the runoff, to rally support for Loeffler and fellow Republican U.S. Sen. David Perdue

It’s a line of attack that could sway moderate suburban voters in a state that hasn’t elected a Democrat to the Senate in 20 years.

“I’m a pastor who is running for political office, but I don’t think of myself as a politician,” he told the Associated Press. “I honestly don’t know anything to be other than authentic.”

Warnock would join a small group of other ministers in Congress, including at least one other Black pastor, Rep. Emanuel Cleaver of Missouri. He said his model was King, “who used his faith to activate change in the public square.” In high school, he listened to the civil rights icon’s sermons and was particularly drawn to “A Knock At Midnight,” in which King exhorts churches to serve as the “critic of the state” and fight for peace and economic and racial justice.

Warnock has embraced that mission. In 2007, he warned that the U.S. could “lose its soul” in a speech that condemned President George W. Bush’s decision to send more troops to Iraq. At the Georgia Capitol in 2014, he was arrested while protesting the refusal of state Republicans to expand Medicaid. After the killing of George Floyd by police in May, he expounded on the country’s struggle with a “virus” he dubbed “COVID-1619” for the year when some of the first slaves arrived in English North America.

Black Church Tradition

His campaign draws heavily from his early life. Warnock grew up poor in public housing in Savannah, Georgia. He cites his father’s small business hauling old cars to a local steel yard to push back on attacks he is against free enterprise.

He attended Morehouse College and earned a Ph.D. in theology from Union Theological Seminary, funding his education with help from student loans and federal grants. His older brother Keith, one of 11 siblings, served more than 20 years in prison for a first-time, drug-related offense, and Warnock has used his case to argue for criminal justice reform.

“He knew what it is to struggle. He knew what it is to go without,” Bishop Reginald T. Jackson, a leader of the African Methodist Episcopal Church in Georgia, said of Raphael Warnock, whom he supports. “He’s able to speak to where a lot of people are.”

Warnock knew early on that he wanted to enter the ministry. His father was also a preacher, and enlisted his son at a young age to help him read the small print in a biblical reference book because he refused to get prescription glasses. Warnock recalled giving his first sermon, “It’s Time I be about My Father’s Business,” at 11.

His social activism is part of a tradition of resistance in many Black churches that developed from the fight against racial inequality. Black pastors have called out the country’s troubled racial history using terms that can be discomforting to outsiders.

In his much-scrutinized sermon, Wright decried the country’s mistreatment of Blacks with the exclamation, “God damn America.” Loeffler has used the clip in an ad that accuses Warnock of defending Wright’s “hatred.”

Loeffler has also used snippets of Warnock’s own sermons to argue that he is against police and the military. In one clip, Warnock says that nobody can serve “God and the military.” Warnock, who has two brothers who are veterans and whose father served in World War II, has said he was preaching from a biblical text and trying to impart a lesson about prioritizing God and laying a moral foundation for life.

Loeffler has used another clip to accuse Warnock of denigrating police. But his remark about “police power showing up in a kind of gangster and thug mentality” in that sermon was a specific reference to police practices in Ferguson, Missouri, that the U.S. Justice Department investigated after a White police officer fatally shot Michael Brown, a Black teenager, in 2014.

“He has actually made sure that we know who he is in his own words,” Loeffler said at a debate in December. “Those aren’t my words.”

Warnock accused her of lying “on Jesus.”

Cleaver said the attacks on Warnock’s sermons using lines with no context are “woefully unfair” and show no understanding of the role of a Black preacher.

“I’m just made sick over what they’re trying to do,” he said.

The effort to paint Warnock as a radical is similar to the strategy Republicans used with some success against other Democrats in down-ballot races this year. But it also echoes the attacks that segregationists leveled against King and supporters of the civil rights movement. That could help turn out the state’s large African American population to vote in next month’s runoff.

Warnock is right to keep focusing on his platform of a living wage, expanded health care options and voting rights, said the Rev. William Barber II, president of the Repairers of the Breach, a nonprofit group that fights poverty and discrimination.

“You don’t win by being Republican lite,” Barber said. “You win by lifting up people from the bottom.”