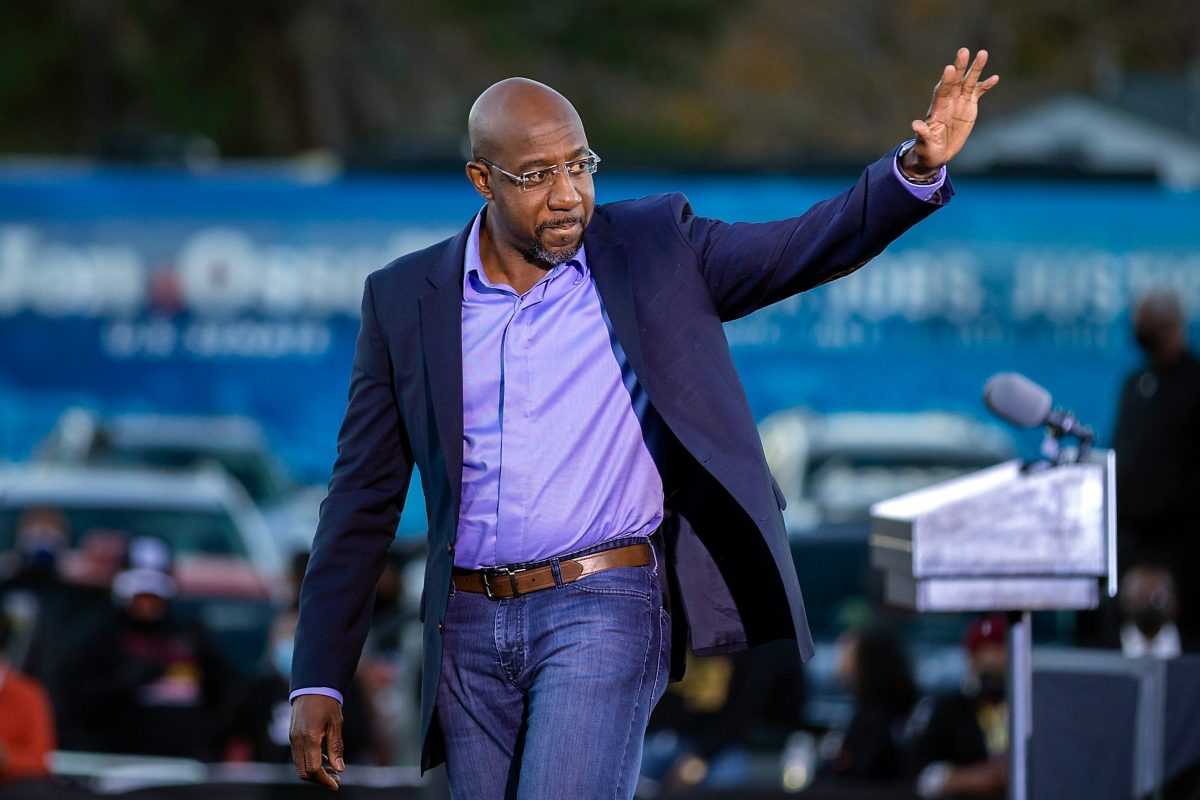

(RNS) — The Rev. Raphael Warnock won one of Georgia’s two runoff elections for U.S. Senate and might be sworn in later this week. Will he be both a pastor and a politician?

Yes, says Michael Brewer, a spokesman for the minister’s campaign, “he will remain senior pastor.”

Marla Frederick, professor of religion and culture at Emory University’s Candler School of Theology, told Religion News Service that an active pastor would not be unknown in the political life on Capitol Hill.

“There are models for doing both/and,” she said.

“The pastorate is one of these careers, these callings, if you will, where you have to stay in such close contact with everyday people and their concerns,” said Frederick. “To the extent that the Senate (is) supposed to represent the concerns of people, it seems to me that someone who’s been a pastor has the capacity to be much more in tune with the kinds of struggles that people are dealing with in their everyday lives.”

Warnock, who has led Atlanta’s Ebenezer Baptist Church since 2005, had something similar to say in a statement to RNS in November.

“It’s unusual for a pastor to get involved in something as messy as politics, but I see this as a continuation of a life of service: first as an agitator, then an advocate, and hopefully next as a legislator,” Warnock said as he was closing in on the top spot of a wide-open primary. “I say I’m stepping up to my next calling to serve, not stepping down from the pulpit.”

He told CNN on Jan. 6 that he thinks grassroots people can help him be effective as a pastor and a senator.

“I intend to return to the pulpit and preach on Sunday mornings and to talk to the people,” Warnock said. “The last thing I want to do is become disconnected from the community and just spend all of my time talking to the politicians. I might accidentally become one and I have no intentions of becoming a politician. I intend to be a public servant.”

With Warnock’s election to the Senate, he can reflect on these other African American ministers who kept up a busy church life while serving in Congress:

Richard Harvey Cain, 1873-75, 1877-79

Prior to being elected a Republican congressman from South Carolina, Cain sought out another form of public service: a volunteer in the Union army. He was rejected, as were many free Blacks at the time, but later he became pastor of Emanuel AME Church in Charleston (where, a century and a half later, the notorious Bible study massacre took place).

“In the House, Cain supported civil rights for freed slaves,” according to Charles M. Christian in Black Saga: The African American Experience: A Chronology. “Cain’s seat was eliminated in 1874, but he remained active in the Republican Party, and was reelected to Congress in 1876.”

In remarks to Congress urging passage of a civil rights bill, Cain spoke of why equal rights for Blacks were justified.

“I ask you to grant us this measure because it is right,” he said in a speech that received loud applause, according to Preaching with Sacred Fire: An Anthology of African American Sermons, 1750 to the Present. “I appeal to you in the name of God and humanity to give us our rights, for we ask nothing more.”

After his tenure in Congress, Cain was elected a bishop of the African Methodist Episcopal Church.

Adam Clayton Powell Jr., 1945-1971

Adam Clayton Powell Jr. (James J. Kriegman/LOC/Creative Commons)

Before, during and after his long service as a Democratic U.S. representative, Powell was pastor of the prominent Abyssinian Baptist Church in New York, where Warnock would serve as a youth pastor decades later.

The authoritative history of the church notes that when Powell arrived in Washington in 1945, one of his first acts as a congressman was an act of civil disobedience.

“(H)e immediately availed himself of the use of the Congressional dining room, which was segregated,” reads the 2014 history Witness: Two Hundred Years of African-American Faith and Practice at the Abyssinian Baptist Church of Harlem, New York. “Powell staged his own successful sit-in.”

The Democrat served as chair of the House Education and Labor Committee, worked on the passage of minimum wage legislation and helped pass laws that prohibited the use of federal funds in the construction of segregated schools.

“As a member of Congress, I have done nothing more than any other member and, by the grace of God, I intend to do not one bit less,” he said about his time in the role.

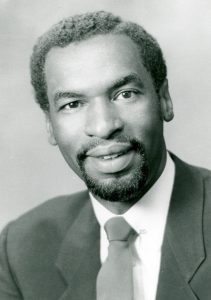

Floyd Flake, 1987-1997

Floyd Flake. (U.S. Congress photo/Creative Commons)

The senior pastor of the Greater Allen AME Cathedral of New York, Flake served 11 years concurrently as a member of Congress and the leader of his megachurch.

Considered the “de facto dean of faith-based economic empowerment,” Flake and his wife, the Rev. Elaine M. Flake, have developed commercial and social projects in Jamaica, New York, such as a corporation focused on preserving affordable housing, a senior citizens center and an emergency shelter for women who are victims of domestic violence.

As a member of Congress, he chaired the Subcommittee on General Oversight of the House Banking Committee. He also helped gain federal funds for projects in his district, including an expansion of John F. Kennedy International Airport. As successful as Flake was, he may have some lessons for anyone trying to fill both a pulpit and a seat in Congress: He resigned his congressional role, saying his priority was his church — where he remains in his leadership role.

“My calling in life is as a minister,” Flake told journalists, “so I had to come to a real reconciliation … and it is impossible to continue the sojourn where I am traveling back and forth to DC.”

John Lewis, 1987-2020

John Lewis. (U.S. Congress photo/Creative Commons)

Lewis, an ordained Baptist minister and civil rights activist, began preaching as a teenager and viewed his work for social justice as connected to his faith. He was the youngest speaker at the March on Washington, addressing the crowd minutes before the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. gave his “I Have a Dream” speech, and served as the chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

Lewis’s work for voting rights led to his being beaten by police as he crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge. Late in his life, he worked with religious group s to address what he considered the “gutting” of the Voting Rights Act by the Supreme Court in 2013.

In 2016, Lewis told RNS he did not regret moving away from traditional ministry.

“I think my pulpit today is a much larger pulpit,” he said. “If I had stayed in a traditional church, I would have been limited to four walls and probably in some place in Alabama or in Nashville, Tennessee. I preach every day. Every day, I’m preaching a sermon, telling people to get off their butts and do something.”

Emanuel Cleaver II, 2005 to present

Emanuel Cleaver II. (Franmarie Metzler/U.S. House Office of Photography/Creative Commons)

Cleaver was senior pastor of St. James United Methodist Church in Kansas City, Missouri, before turning the pulpit over to his son in 2009. The chair of the House Subcommittee on National Security, International Development and Monetary Policy, he has co-authored a reform bill on housing programs. He also was instrumental in the creation of a Green Impact Zone in which federal funds created jobs and energy efficient projects in a 150-block area of Kansas City known for crime and unemployment.

As the 117th session of Congress opened this week, Cleaver drew attention and ire for ending his invocation in the name of “God known by many names by many different faiths — amen and awomen.”

He told a local TV station that the prayer was a nod to the diverse Congress where more women are serving than ever before.

“After I prayed, Republicans and Democrats alike were coming up to me saying ‘thank you for the prayer. We needed it. We need somebody to talk to God about helping us to get together,’” he told KCTV. “It was a prayer of unity.”