When Rev. Raphael Warnock, a Black Baptist pastor in Georgia, placed his hand on a Bible last week and took the oath of office to join the U.S. Senate, he assumed a congressional seat previously held by Joseph Emerson Brown, an infamous White Southern Baptist politician who enslaved Black people. But to get to that position, Warnock had to overcome criticisms from a new generation of Southern Baptists — including by Al Mohler, a man who spent the last 15 years in a chair named in honor of Brown.

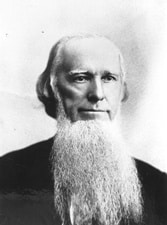

Brown, who enslaved five persons in 1850 and 19 in 1860, served as Georgia’s governor when the state seceded from the nation to join the Confederacy. After the Civil War, he became chief justice of the Supreme Court of Georgia and later a U.S. Senator. In that post-Reconstruction period, Brown built a fortune off the exploitation of mostly black convict-lease laborers, a system that scholars have called “slavery by another name.”

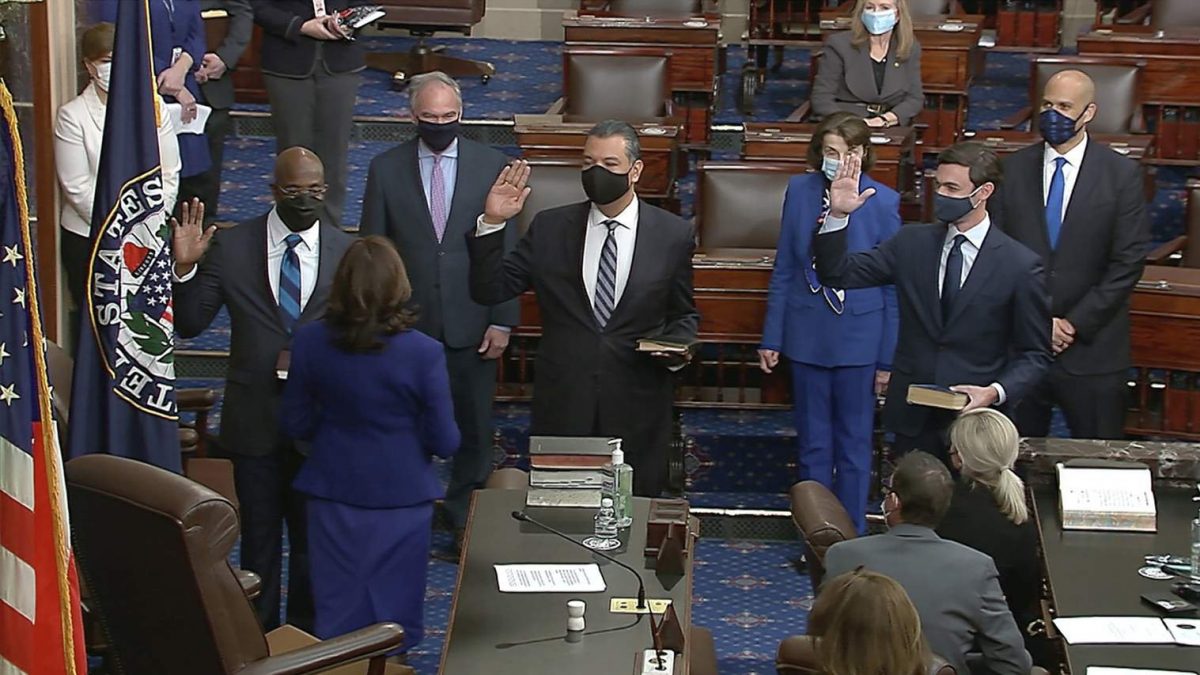

Vice President Kamala Harris swears in ( from left) Sen. Raphael Warnock, D-Georgia; Sen. Alex Padilla, D-California; and Sen. Jon Ossoff, D-Georgia, on the floor of the Senate on Jan. 20, 2021. (Senate Television via AP)

Warnock serves as pastor of the Ebenezer Baptist Church, which sits just about a mile from the state’s Capitol building where Brown had lain in state honors upon his death in 1894. A statue of Brown sits just around the corner on the Capitol grounds from one of Martin Luther King, Jr., who served as co-pastor of Ebenezer at the time of King’s assassination.

The Other Brown Chair

In 1880, the same year he joined the U.S. Senate, Brown gave a massive gift to Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Kentucky, that saved the fledging school from closure. A board member from 1872-1877 and 1880-1894 (and chair from 1883-1894), Brown’s leadership and money made him the most significant 19th century figure for the school after its four founders, who were also all enslavers.

Joseph Emerson Brown

The school honored Brown with the creation of the “Joseph Emerson Brown Chair of Christian Theology.” In 2005, SBTS trustees elected Mohler to that chair. Mohler, president since 1993, said at the time that being named to that chair “means more than I can say.”

“It also is a reminder that the Lord has used significant individuals [such as Brown] to make this institution what it is,” Mohler added. “Some of these names are inscribed on buildings, some are memorialized in scholarship and professorships, and it is easy for us to forget what they meant and who they were.”

Amid a push last year by some Baptists who urged SBTS to remove the names of its enslaver founders from buildings on campus, Mohler bristled at such suggestions. He did, however, request the trustees vacate the Joseph Emerson Brown Chair, which they did.

Mohler explained that while he knew of Brown’s support of the Confederacy and slavery when he accepted the honorary chair 15 years earlier, he didn’t know about his profiting from convict leasing. When SBTS documented its history with slavery and racism in a December 2018 report, it included significant information about Brown and convict leasing. Yet, Mohler stayed quietly in the chair until 2020, when he called his earlier defense of slavery “stupid.”

In August, while still sitting in the Joseph Emerson Brown Chair of Christian Theology, Mohler attacked Warnock for campaigning to take Brown’s old seat in the U.S. Senate. He knocked Warnock for attending Union Theological Seminary in New York since it is what Mohler called “the flagship institution of liberal Protestantism.” He also attacked Warnock’s position on abortion, suggesting Warnock has an “obsession and idolatry with autonomy.”

Mohler even suggested Warnock isn’t really a Christian and wants a “complete transformation of Christianity.”

“A new theology that denies the basic truths of the gospel, that denies the authority of scripture, that denies the historicity of the very events central to Christianity, that redefines all Christian doctrine and of course eventually redefined all Christian morality,” Mohler said.

Then in December, Mohler claimed Warnock, the first Black Senator from Georgia, “may be the most radical candidate conceivable from a state like Georgia.”

Others Join the Attacks

Mohler was not the only White Southern Baptist to suggest Warnock — and not Brown or the other enslavers who previously held that seat — would be the “radical” senator.

Sen. Lindsey Graham, a Southern Baptist in South Carolina, called Warnock “the most radical person to ever run for Senate in the history of Georgia.” That list of senators includes not only Brown but several other enslavers and Confederates, as well as segregationists who fought the civil rights movement led by Ebenezer’s co-pastor.

Rep. Doug Collins (center) during a U.S. House Judiciary Committee hearing on July 29, 2019. (Donna Burton/U.S. Customs and Border Protection/Public Domain)

Former U.S. Rep. Doug Collins, who ran unsuccessfully in the Senate election that Warnock won, offered an even harsher assessment. A pastor of a Southern Baptist church before running for office, Collins claimed Warnock’s pro-choice politics meant he could not really be a pastor.

“What you have is a lie from the bed of hell. It is time to send it back to Ebenezer Baptist Church,” Collins declared at a campaign event.

And several Republicans even played short snippets of some of Warnock’s sermons to claim he was somehow unpatriotic or even unchristian, and thus suggested he was unqualified for office because of his religious teachings.

Despite the campaigning by Graham, Collins, and others, Warnock became the 11th Black U.S. Senator in history. And his election in the Deep South could signal a change in American politics. It already represents a significant historical change in Georgia.

“I did not say that the negroes are equals of the white race. God did not make them so; and man can never change the status which the Creator assigned to them,” Brown argued shortly after the Civil War. “They will never be placed upon a basis of political equality with us.”

Then in 1881, Brown wrote to then-SBTS president James P. Boyce about his fear that Blacks would gain political power and end White rule.

“I am glad you take what seems to me to be the proper view of the situation here,” Brown wrote to Boyce. “There is going to be a very serious effort made to put it into execution all over the south which would virtually put the white race back under the domination of the colored.”

One hundred-and-forty years later as Warnock sits in Brown’s old seat in the U.S. Senate, Brown’s chair may be gone at SBTS, but the name of Boyce, an enslaver and Confederate soldier, remains on the library and undergraduate college.

For Brown and Boyce, Warnock as a U.S. Senator would surely seem quite “radical.”