On the last Sunday in May, former Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary President Paige Patterson stood in one of America’s most prominent pulpits — that of First Baptist Church in Dallas — and claimed a “lynch mob” was out to get him. This insensitive metaphor by a White preacher was all the more shocking because of Patterson’s geographical ignorance. Had he walked a third of a mile from that church, he would have stood where a literal lynching occurred.

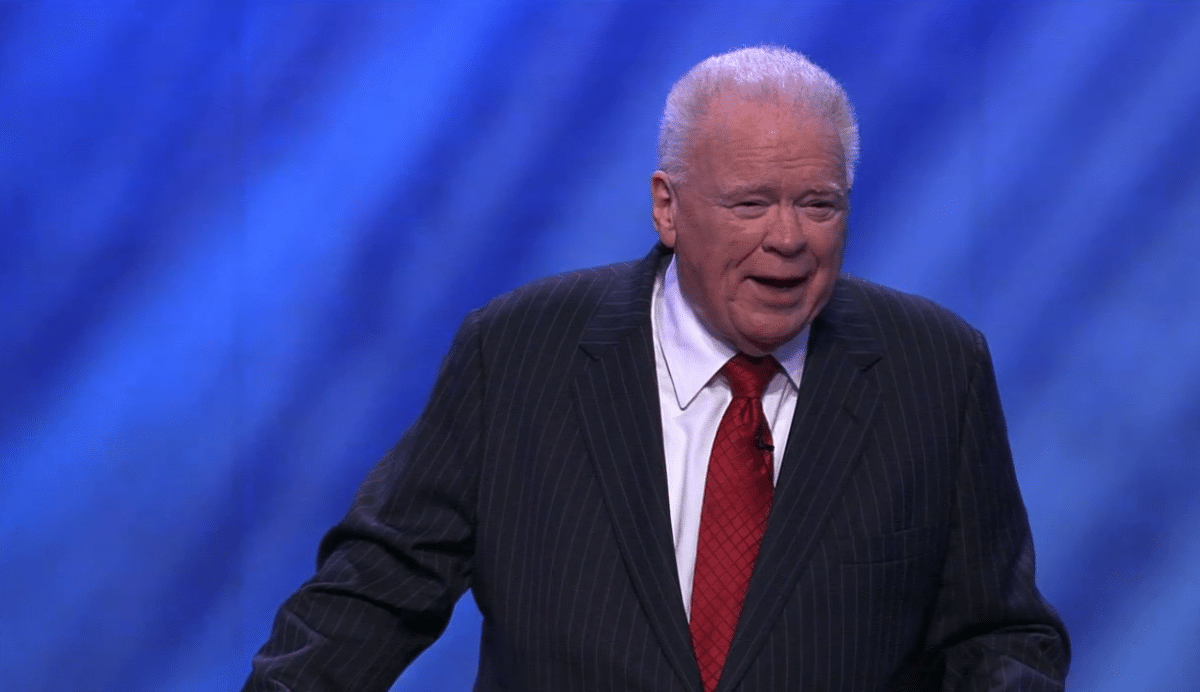

Screengrab Screengrab as Paige Patterson preached in the 9:15 service at First Baptist Church in Dallas, Texas, on May 30, 2021.

Patterson’s misappropriation of the term was presumably intended to reframe himself as a victim. He was fired in 2018 by SWBTS for mishandling reports of student sexual assaults. New allegations emerged last month, with the school publicly accusing Patterson and his wife of having “continued to use institutional records for their own personal benefit and to the detriment of the Seminary.” The most serious charge involves the redirection of millions of dollars away from SWBTS to the benefit of a nonprofit controlled by the Pattersons.

On top of that, Patterson has also been accused of making racist comments. He wrote a letter arguing that the first Black SBC president might lead to a theological backslide since “among many of the ethnic groups there are not so many of them who understand the issues involved and the seriousness of them.” And he allegedly criticized the hiring of a Black SBC employee, calling her “that Black girl.”

Despite the seriousness of these reported misdeeds and cautions from J.D. Greear, the current president of the Southern Baptist Convention, against inviting Patterson to preach because of them, Robert Jeffress welcomed the disgraced leader into FBC’s pulpit and gallingly claimed to the congregation that Patterson did “a marvelous job” leading the seminary.

Following this whitewashed introduction, Patterson stood before a congregation gathered to worship God and described “the lynch mob that I saw out there trying to get hold of me.” Like so many others decrying “cancel culture,” he appears to be upset about efforts to hold him accountable for a litany of misdeeds. Yet, employing the “lynch mob” analogy does a disservice to the real victims.

Like Allen Brooks.

In 1910, a mob of about 5,000 people took Brooks from a county courthouse and dragged him several blocks to the intersection of Akard and Main Streets. They lynched him there under the silent gaze of FBC’s steeple and the acquiescence of the congregation.

O.S. Hawkins, a former pastor of First Baptist and an SBC leader, criticized the silence about the Brooks lynching. He noted several leaders of the local Ku Klux Klan were also prominent members and deacons of the church. Hawkins thinks this awkward truth could explain “such silence against such evil” by the pastor, George W. Truett, “man of otherwise remarkable reputation and stature.”

“[Truett] stood by silently as he watched those under his pastoral watch-care become actively involved in the promotion of the vilest expression of racial hatred in our nation’s history,” Hawkins added. “His racial sins were more sins of omission than commission but glaringly so. It is not what he said but what he did not say in the face of such flagrant disregard for human dignity and life.”

Indeed, such silence from the pulpit only added to the injustice that occurred. The tragedy of Brooks reminds us what a real lynch mob looks like. It is an expression of grotesque violence that’s more about racial hatred than punishment.

A lynch mob is NOT a wealthy, White man being fêted by a nationally-famous preacher who had the ear of the last U.S. president. A lynch mob is NOT condemnation vocally leveled against such a man for turning a blind eye to reports of rape or misusing financial resources. A lynch mob is NOT someone being able to comfortably live in a $1 million dollar house purchased for him by his personal nonprofit. A lynch mob is NOT a White man with a history of racist remarks now facing accountability.

To state the obvious: Patterson is NOT being lynched. Instead of cheerleading him on and remaining silent about his misdeeds, Jeffress might consider learning a lesson from the mistake of his predecessor who remained silent in the face of injustice.

Brian Kaylor is president & editor-in-chief of Word&Way. Follow him on Twitter: @BrianKaylor.