(RNS) — Members of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops have voted to draft a document on the Eucharist, green lighting a controversial effort championed by a group of conservative clerics who have called for denying Communion to President Joe Biden and other Catholic Democrats who support abortion rights.

The vote was announced Friday (June 18) on the final day of the USCCB’s annual spring meeting, with 168 voting yes, 55 voting no and six abstaining. The proposal to draft a document on “Eucharistic consistency” required a simple majority to pass. The announcement followed more than two hours of extended debate between clerics on Thursday evening, with dozens of bishops delivering impassioned speeches for and against the proposal.

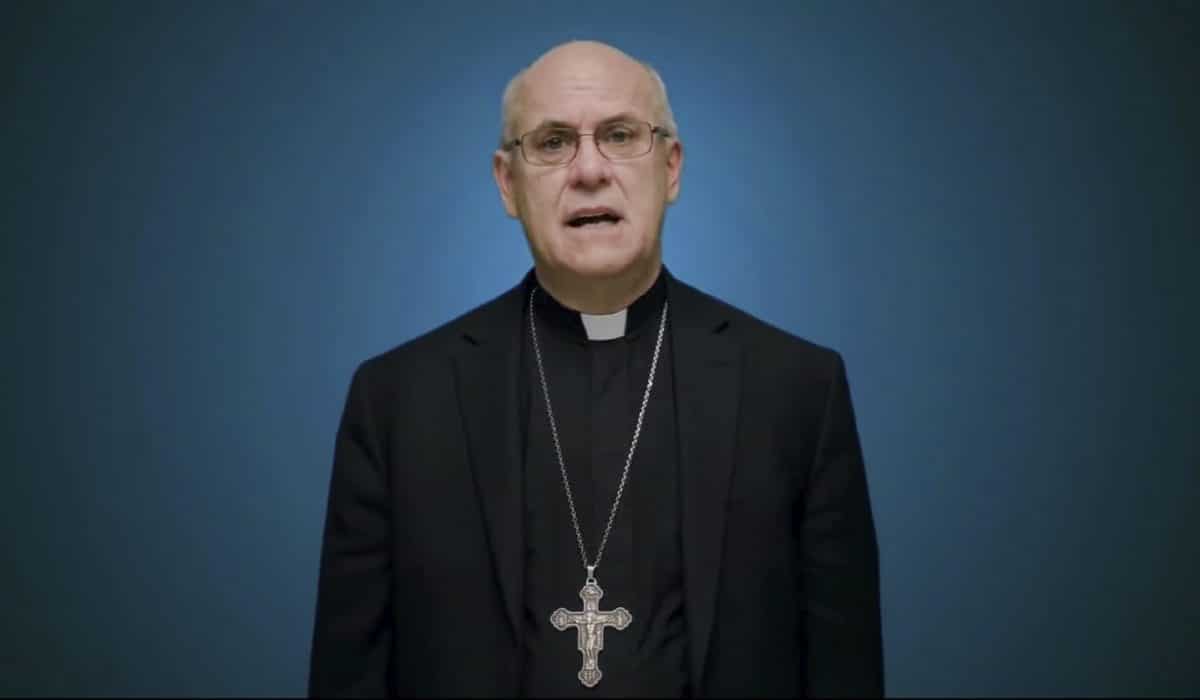

In this screengrab, Bishop Kevin Rhoades of Fort Wayne-South Bend, Ind., head of the doctrine committee for the U.S Conference of Catholic Bishops, addresses the body’s virtual assembly regarding a formal statement on the meaning of the Eucharist in the life of the church on June 17, 2021. (United States Conference of Catholic Bishops via AP)

Bishop Kevin Rhoades of Fort Wayne-South Bend, Indiana, who chairs the U.S. bishops’ Committee on Doctrine, insisted throughout the three-day conference that the proposed document isn’t meant to single out any particular group or issue, much less a specific lawmaker. But bishops who spoke at the virtual gathering made plain the political subtext, with multiple clerics specifically referencing Biden, a Catholic, and intimating he should not receive Holy Communion.

While voicing support for the document on Thursday, Archbishop Joseph Naumann of Kansas City insisted that “it’s not the bishops that have brought us to this point — it’s really, I think, some of our public officials.”

He then criticized Biden for his abortion policies and for describing abortion as a “right,” adding, “this is a Catholic president that’s doing this, the most aggressive thing we’ve ever seen in terms of this attack on life — when it’s most innocent.”

Critics of the proposal expressed concern about its development and what they characterized as a narrow focus on abortion, arguing it will add to partisan rift.

“Any effort by this conference to move in support of the categorical exclusion of Catholic political leaders based on their public policy will thrust the bishops of our nation into the very heart of the toxic partisan strife, which has distorted our own political culture and crippled meaningful dialogue,” said Cardinal Joseph Tobin of New Jersey, who opposed the measure.

“The debate and vote demonstrated serious divisions among the bishops on the current proposal and process,” John Carr, co-director of the Initiative on Catholic Social Thought and Public Life at Georgetown University, and a former USCCB staffer, said in an email. He noted that while the proposal’s detractors were outvoted, opposition was substantial, saying “it is unprecedented for the Conference to simply push forward when so many bishops are opposed.”

Carr speculated some bishops made have been persuaded by assurances the proposed statement “will not include policy or guidance on denying communion to the President or other public officials,” adding, “it seems that the future statement is expanding in scope and shrinking in specific application to public officials.”

The vote on the proposal — which advocates describe as a broad “teaching document” that does not overrule the right of individual bishops to decide questions of Communion denial for their own diocese — was the culmination of a years-long controversy that stretches from a South Carolina church to the White House to the Vatican, with Catholic prelates giving voice to a range of opinions about whether politicians who back abortion rights should be denied the Eucharist.

The issue first garnered national attention in 2004, when a small group of bishops threatened to deny Communion to then-candidate John Kerry because of his abortion stance. Kerry appeared to avoid such rejection, but the controversy dogged his campaign all the same. The USCCB eventually produced a document about what it means to “worthily” receive the Eucharist in 2006, which stated Catholics who “knowingly and obstinately repudiate” the church’s moral teachings should “refrain” from Communion.

It wasn’t until 2018 that the issue of Communion denial again intersected with high-profile politics, albeit in a different context: At the bishops’ spring meeting in Florida that year, a bishop recommended instituting “canonical penalties” for Catholics who participated in the policy of forcibly separating immigrant families along the U.S.-Mexico border instituted by then-President Donald Trump’s administration. The proposal did not gain traction, however, and did not trigger calls for a Eucharistic document.

A year later, then-presidential candidate Joe Biden was reportedly denied Communion by a priest in South Carolina because of his abortion stance. The rebuke garnered little attention at the time, sparking speculation that the practice had lost its political luster.

But all that changed shortly after media outlets announced in November that Biden would become the nation’s second Catholic president. Although the Vatican congratulated Biden on his victory, the USCCB published a far more cautious pronouncement that, among other things, criticized his abortion policies. The group of bishops then promptly created a (since disbanded) committee to study how they would respond to his presidency.

The contrast between the USCCB and the Vatican regarding Biden continued for months, as conservative bishops began openly proclaiming he should be denied Communion. Clerics such as Cardinal Wilton Gregory of Washington, D.C., insisted they would grant the president the Eucharist anyway (he told RNS he doesn’t “want to go to the table with a gun on the table first”), but an incoming bishop in Biden’s home diocese of Wilmington, Delaware, declined to give a straight answer when asked whether he would extend the sacrament to Biden.

When a proposal to draft a document on the Eucharist was put on the agenda for the USCCB’s June meeting, Cardinal Luis Ladaria, the prefect for the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, sent a letter to USCCB President Jose Gomez, the Archbishop of Los Angeles, urging the conference to tap the brakes on the Eucharist discussion. The head of the Vatican’s doctrinal watchdog argued the effort could suggest abortion and euthanasia are “the only grave matters of Catholic moral and social teaching that demand the fullest level of accountability on the part of Catholics” — a notion he called “misleading.”

Gomez pushed forward regardless, although multiple bishops referenced Ladaria’s letter during Thursday’s debate, arguing the proposal is too politicized and that USCCB leaders have not heeded the Vatican’s call to take its time and convene with other bishops’ conferences.

The future of the proposal remains unclear. It will be brought before the USCCB’s fall convening in November, and Carr noted it will require a two-thirds vote for adoption rather than a simple majority — a bar that appears more achievable after the most recent vote.