Evangelicals share the recognition of the Bible as the ultimate authority. Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

A precipitous decline in the number of Americans identifying as white evangelical was revealed in Public Religion Research Institute’s 2020 Census on American Religion. In 2006, almost a quarter of the American population identified as white evangelical, but only 14.5% the population does so today.

Evangelical is an umbrella category within Protestant Christianity. The category of evangelical is complicated; unlike Catholics, who have a centralized authority, evangelicals do not maintain a single spokesperson or institution. Instead, evangelicalism in the United States today is composed of several institutions, churches and a network of largely conservative spokespersons.

Consequently, there are a variety of churches, theologies and practices within evangelicalism. They include certain groups such as Baptists, Methodists and nondenominational churches, among others, many of which are members of the National Association of Evangelicals.

So what constitutes an evangelical, or what is evangelicalism in the United States today?

Conversion and Converting

One place to begin is historian David Bebbington’s four-part definition of evangelicalism. In his 1989 book, Bebbington argued that evangelicals share a recognition of the Bible as the ultimate authority, emphasize the work of Jesus’ crucifixion in human salvation, share a born-again experience and are active socially in reforming society.

Most Christians recognize the authority of the biblical text and the centrality of Jesus’ crucifixion. The born-again conversion experience and a particular kind of social engagement separate evangelicals from other types of Christians in the United States. For evangelicals, the born-again experience is the only way that any individual can gain access into heaven in the afterlife. All other religious alternatives are rejected.

Born-again represents a new life that evangelical converts gain when they recognize the redemptive power of Jesus’ death and resurrection. Generally, the born-again experience is enacted when individuals recite the “sinner’s prayer.” This simple religious ritual acknowledges the individual’s imperfection in this life, a request to be guided by God for the remainder of the individual’s life and a promise of a blissful afterlife.

For most evangelicals, the born-again moment signifies a fresh start or a cleansing of one’s soul – old mistakes are forgotten by the divine. Afterward, baptism, a ritual water purification, follows.

An expectation for all new evangelical converts is that they will eventually participate in evangelizing – sharing their Christian experience with others in the hopes of leading others to a born-again experience.

There are some theologically specific differences within evangelicalism. Internal debates focus on such topics as speaking in tongues or the role of women in leadership. Speaking in tongues is thought by charismatic or Pentecostal evangelicals to be the ability to speak in different or angelic languages to transmit a message from the divine.

Like a diversity of ideas related to speaking in tongues, some denominations deny that women can be pastors or ministers while others ordain women into the ministry. There are popular female evangelical authors, such as Joyce Meyer, and televangelists, such as Paula White, a spiritual adviser to former President Donald Trump.

Political Engagements

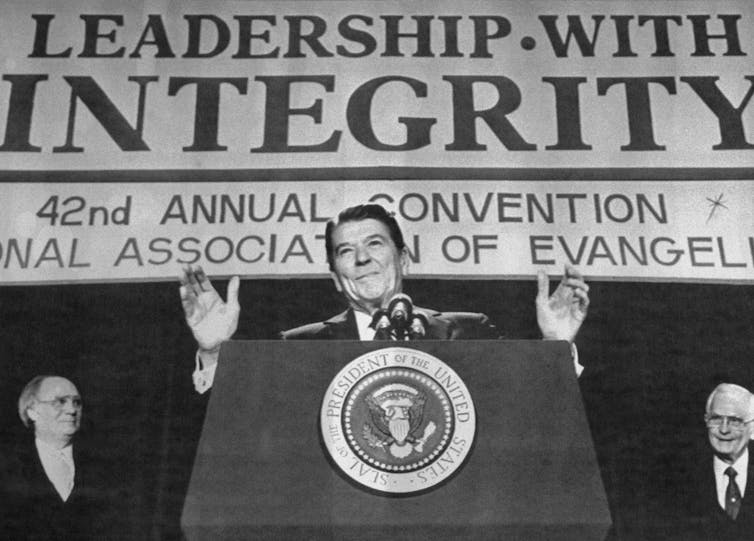

As a scholar of religion in America, I’ve seen how evangelicalism in the United States is generally recognized for its political allegiances with the Republican Party. Since the Ronald Reagan era, evangelicals have overwhelmingly supported Republican presidential candidates. This is ironic, as President Jimmy Carter, who identified as a born-again Christian, lost evangelical support to Reagan, who identified as Christian. But as religion scholar Randall Balmer noted, Reagan “seemed a tad uneasy about the label” of evangelical.

Evangelicalism in the United States is composed of institutions and networks of conservative Christians working to spread its ideologies in the political sphere. Organizations like evangelical author James Dobson’s Focus on the Family, along with lobbying groups like political consultant Ralph Reed’s Faith & Freedom Coalition, remain influential in attempting to shape the American government into an evangelical worldview.

Politically, evangelicals are extremely active in advancing anti-abortion, anti-same sex marriage and “family values” positions in an effort to restore the country to its perceived Christian roots.

But not all evangelicals agree about politics. Within evangelicalism there exist racial differences. Many sociological projects highlight the political distinctions in voting patterns and on social issues between white and Black evangelicals.

Exiles, Marginals and ‘Dones’

Some people raised within evangelicalism are rejecting the faith’s rigid boundaries and constraints today. There are a growing number of “exvangelicals” – those who were insiders who no longer fit the parameters. Many within the exvangelical movement have voluntarily left. However, others describe their departure as exilic, or having been forced out because of their views and lifestyles.

Using forms of social media, many exvangelicals are sharing their stories and exposing the theology and church practices negatively affecting their lives.

Changes in theology often result in political alterations as well. For instance, exvangelical podcaster and blogger Blake Chastain wrote, “As more and more people question the teachings of their white evangelical churches, they will inevitably consider the consequences of its social and political actions.” Many younger evangelicals reject, for example, evangelicalism’s resistance to immigration expansions and gay marriage.

Some raised within evangelicalism remain in the margins of evangelicalism. Liberal forms of evangelicalism exist – albeit in the minority – including some featuring progressive evangelical churches that accept members of the LGBTQ community, question the reality of hell and read the Bible less literally. Some within these circles debate whether the label of evangelical is redeemable, while others reject the moniker entirely.

The future of evangelicalism in the United States is undetermined, but some within the tradition are calling for serious reflection regarding evangelicalism’s political stances. For instance, some evangelicals are critical of white evangelicals’ Christian nationalism, which is defined as “a set of beliefs and ideals that seek the national preservation of a supposedly unique Christian identity.” Others are questioning political allegiances and race relations.![]()

Terry Shoemaker is a lecturer in religious studies at Arizona State University. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.