“Five hundred twenty-five thousand six hundred minutes.”

The length of a year. The cast in the Broadway musical Rent sang out those words to ask a more fundamental question: “How do you measure a year in a life?” It’s more than just minutes. It’s daylights, sunsets, midnights, cups of coffee, laughter, strife, and love. As the cast from Rent put it, “Five hundred twenty-five thousand moments so dear.”

Many of us may feel like the last year — wait, year-and-a-half and still counting — has left us a bit imprisoned by lockdowns, masks, canceled trips, and worries about loved ones. Perhaps we are thinking a bit more carefully about time, lost opportunities, and wasted moments.

The average life expectancy in the U.S. today is right around 77.3 years. The drop related to COVID-19 deaths last year puts this at the lowest level in two decades. That still means the typical person gets over 28,200 days on this earth (don’t ask us to calculate, or sing, the math on the number of minutes). While our eternal futures belong to God, each of us must steward our earthly lives well. All of us know people who squander this precious resource on superficial things only to arrive at the end full of regrets.

Lamar Johnson’s years have been wasted. More accurately, the criminal justice system has stolen nearly 10,000 days and his daylights, sunsets, midnights, cups of coffee, laughter, strife, and love that would’ve occurred. Denied his liberty, he watches time go by knowing he is an innocent man and knowing that others — even those in power — believe that too.

In 1995, Johnson was convicted of murdering a friend. Sentenced to life in prison without parole, this punishment ensured he would never be released. But Johnson was not the killer.

At the time of the murder, he was miles away from where it occurred. Two others confessed to the dastardly deed. Despite all this, he remains condemned by society.

How Lamar Johnson ended up in prison and why he still remains in a cell on the outskirts of Jefferson City, Missouri, reveals how the phrase “criminal justice system” can be an oxymoron. An injustice is perpetuated each day that he wakes up and goes to sleep behind bars. Five hundred twenty-five thousand six hundred injustices are committed against him each year. Leaders with the ability to right this wrong refuse to take action, claiming to act on principle but politics clearly lurk underneath their inactions and deflections.

In this issue of A Public Witness, we take a closer look at the injustices of Johnson’s case and what is needed to secure his freedom. We also introduce you to Johnson through an exclusive interview with this brother in Christ as he speaks from behind prison bars.

Injustices Upon Injustices

“Prosecutors have a constitutional and ethical obligation to ensure that innocent people do not get punished,” wrote Pace University law professor Bennett Gershman. “As the number of exonerated defendants continues to grow, however, it becomes increasingly clear that prosecutors, either by affirmative acts of misconduct, or a failure to carefully and responsibly scrutinize the quality of the evidence, sometimes do contribute to defendants’ wrongful convictions.”

Recognizing that mistakes are made, reform-minded prosecutors across the country are reexamining questionable convictions in the interests of justice. When St. Louis Circuit Attorney Kim Gardner established her own “conviction integrity unit,” Lamar Johnson’s case was one of the first reviewed by her office.

That investigation cited financial payoffs to witnesses (by previous prosecutors in the St. Louis County Attorney’s office), fabricated witness statements, and police misconduct during the lineup that “identified” Johnson as the killer. The detective who allegedly committed these misdeeds remains on the job despite calls from St. Louis area faith leaders for his termination.

Gardner’s office sought to overturn Johnson’s conviction. Detailing her request in a court filing, she wrote, “When a prosecutor becomes aware of clear and convincing evidence establishing that a defendant in the prosecutor’s jurisdiction was convicted of a crime that the defendant did not commit — the position in which the circuit attorney now finds herself — the prosecutor is obligated to seek to remedy the conviction.”

Eric Schmitt, Missouri’s Attorney General (and now a U.S. Senate candidate), opposed Gardner’s motion. In both legal filings and courtroom arguments, Schmitt’s office asserted that the window for legally granting a new trial had passed and the jury conviction against Johnson should stand. The Missouri Supreme Court sided with the Attorney General.

The verdict wasn’t about Johnson’s guilt but whether the “justice” system should even be concerned about that detail. Avoiding the question of Johnson’s culpability, the Court stated, “This case presents only the issue of whether there is any authority to appeal the dismissal of a motion for a new trial filed decades after a criminal conviction became final.” The justices concluded, “No such authority exists; therefore, this Court dismisses the appeal.”

In other words, Missouri’s chief legal officer and its highest court preferred Johnson’s incarceration continue despite the evidence of his innocence. The finality of the process received preference over the accuracy of a sentence. Justice was not served.

A rally outside the Missouri Supreme Court building in Jefferson City, Missouri, led by the NAACP and Missourians for Alternatives to the Death Penalty to push criminal justice reform on June 5, 2018. (Brian Kaylor/Word&Way)

Partially in response to the ruling, the state legislature passed a bill then signed into law by Gov. Mike Parson that creates a pathway for wrongful convictions to be reconsidered. As Johnson awaits that possibility, his lawyers filed a habeas corpus petition. Meanwhile, the governor rushed to pardon Mark and Patricia McCloskey — the wealthy White St. Louis couple who pleaded guilty to pointing firearms at peaceful Black protesters — but has yet to act on behalf of Johnson or another Black Missouri man prosecutors say is wrongly imprisoned, Kevin Strickland.

“It is mind-boggling — and truly appalling — that the individuals Missouri Gov. Mike Parson (R) has found time to pardon are the unrepentant gun-toting McCloskeys and not two Black men who have suffered the grave injustice of being locked up, with no end in sight, for crimes they did not commit,” the Washington Post wrote earlier this month. “Every single day they spend in prison is an affront and an injustice.”

While powerful people avoid or even oppose acting in the name of justice, all of us carry some guilt for tolerating Johnson’s continued incarceration.

“Presumptions of guilt, poverty, racial bias, and a host of other social, structural, and political dynamics have created a system that is defined by error, a system in which thousands of innocent people now suffer in prison,” activist Bryan Stevenson wrote in Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption. “We are all implicated when we allow other people to be mistreated. An absence of compassion can corrupt the decency of a community, a state, a nation.”

This is a free issue of A Public Witness. If you’re not a paid subscriber, upgrade today so you don’t miss any future issues!

Faith Behind Bars

“I believe that everything we face in this life is either a trial or a consequence,” Lamar Johnson shared via email. “In that sense, I believe that the principles of those leaders with the power to address my situation who are vocal about their Christianity are being tested.”

One of us (Beau) is more than just an observer of Johnson’s case. Through a member of the congregation he pastored at the time, Beau met Johnson several years ago. At her urging, Beau signed on as Johnson’s “spiritual counselor” and began visiting him in prison. The two have met in-person at least a half-dozen times (COVID-19 interrupted this too), email regularly, and talk on the phone on occasion. The quotes from Johnson included in this story are from such correspondence and shared with his explicit permission.

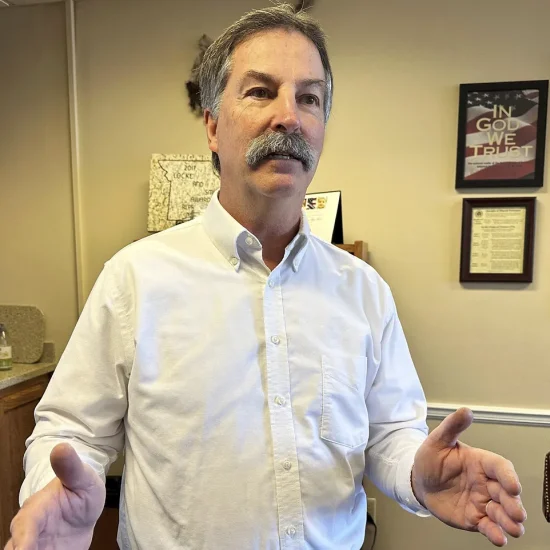

Beau Underwood (left) and Lamar Johnson (right) stand with the church member who introduced them.

What is remarkable about Johnson is not only the unfairness of his continued incarceration but the heart and character of a man who has endured so much. Despite all the wrongs perpetrated against him, he refuses to become resentful.

“I’ve had countless moments of despair throughout my incarceration,” Johnson said after being asked how he maintains his optimistic spirit. “Everything from an unfair decision to deaths in my family have shaken my faith and, at times, even made me question God’s very existence. But something always followed that reminded me that God’s promises are true and convinces me that he has a plan for my life other than prison.”

This was not always his outlook on life. Johnson grew up in a St. Louis housing project and regularly attended a Baptist church as a child. That congregation played a positive role in his life.

“Unfortunately,” he recounted, “as I was entering my early teens, the church closed, leaving me with little to do except hang out in my neighborhood. With my father not around and my mother forced to work all the time, I got much of my influence from all that was happening around me. By my mid-teens, like many in my neighborhood, I got involved with drugs naively thinking that could somehow lead to a better life.”

That lack of support also influenced his relationship with God. Like many Christians, he started viewing God solely as a help in times of trouble.

“When I did think about [God], it was only when I was in trouble and only long enough for him to get me out of the situation I was in,” Johnson said. “As soon as he did, in spite of all the bargaining and promises I made, I’d go right back to living mainly for myself again.”

Since then, Johnson’s faith matured. This includes moments of honesty like those found in many of the biblical psalms or the words of Job.

“For many years I blamed God for all that happened in my life. I vowed that if I ever got the chance, I would, like the man on the beach [in the poem “Footprints in the Sand”], confront God and demand to know where he was when I needed him most,” Johnson explained. “Only in recent years did I come to understand that God has always been both walking beside and carrying me.”

“I then made a new vow: That if I ever got the chance, instead of asking God’s thoughts about all that happened in my life, I would ask God what he thought about what I was DOING with my life,” Johnson added.

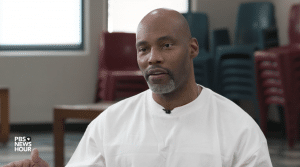

Screengrab of Lamar Johnson speaking during an interview for PBS News Hour on July 15, 2021.

For now, what Lamar Johnson can do with his life is restricted by concrete walls, iron gates, and barbed wire fencing. It is limited by a system that efficiently removes people from society but is slow to provide redress. His case is garnering more attention and publicity, but it is still far from a cause célèbre . The legal and political system of Missouri keeps Johnson behind bars, but most Missourians don’t even seem to know about the injustice done in their name.

Redemption

While U.S. Christianity often focuses on the afterlife, Johnson is still looking to be rescued in the here and the now.

“Redemption for me would be simply being released from prison and allowed to live out the rest of my life in peace with my family and friends,” Johnson said.

As for the broader criminal justice system? Well, he has a few thoughts there as well.

“Redemption for our criminal justice system would first require acknowledging that the system makes far more mistakes than believed. If just 1% of the estimated 2 million people incarcerated in the U.S. are innocent, that is still 20,000 people wrongfully languishing in prisons across the country,” he explained.

“Then, redemption for our criminal justice system would next require implementing the recommendations of countless individuals, committees, and organizations that have studied wrongful convictions,” he added. “This includes, but is not limited to, improving eyewitness identification procedures, videotaping all police interviews, barring jailhouse snitch testimony, disciplining bad law enforcement officials, and adequately funding the public defender system.”

We agree with his suggestions for reform. And we hope the redemption begins with his case.

Unfortunately, Christians often fail to evaluate issues related to criminal justice according to the teachings of their faith. When the Barna Group surveyed Christians on the topic, a relatively small minority said their church engaged the issue. Respondents ranked it at the bottom of their own priorities. Furthermore, the poll revealed wide misperceptions about national trends in crime rates and incarceration levels.

“When we are shaped and formed by the kingdom of God, that means that we’re going to have a different vision — a different view of what matters,” evangelical ethicist Russell Moore told a symposium of evangelical Christians calling for criminal justice reform. “And a different vision and a different view of who matters.”

That is the question facing Christians, political leaders in Missouri, and our whole society: Does Lamar Johnson (and others like him) matter? Do we care about the government, which operates with our authorization and on our behalf, denying his freedom and squandering his days?

Recognizing prisoners as people having inherent dignity and worthy of respect regardless of their crimes is difficult. Incarceration creates a social stigma that has lasting effects both for those in prison and those reentering society. As James Forman Jr., a law professor at Yale wrote, “People convicted of crimes often become social outcasts for life, finding it difficult or impossible to rent an apartment, get a job, adopt children, access public benefits, serve on juries, or vote.”

It is easy — and likely accurate — to suspect that Johnson remains in a cell because releasing convicted murderers, even when they obviously did not commit the crime, is unpopular among voters and, thus, low on the priority lists of politicians. Johnson’s circumstances are not reviewed strictly on the merits of his case or the demands of justice. He is judged by where he sleeps, the jumpsuit he wears, and the color of his skin. Facts have difficulty winning out over prejudices, stereotypes, and racism.

And that is precisely why Christians must pay attention and speak out. In Matthew 25, Jesus tells his followers quite explicitly that what we do on behalf of the “least of these” we do for him. How we treat the most vulnerable is a test of our discipleship. In them, we encounter Christ and our response must reflect that reality. Failing to respond in faith results in judgment.

Jesus’s warning specifically references those behind bars: “I was a stranger and you did not invite me in, I needed clothes and you did not clothe me, I was sick and in prison and you did not look after me” (Matthew 25:43).

That means Lamar Johnson’s case is a test for the Church. In his suffering, we see Jesus. How can we be indifferent to his circumstances? How can we refuse to help our brother who is being unfairly punished? His plight must be more than a tragic story or a test of our politics. It is either an opportunity to witness to the justice God demands or a chance to deny our Savior. We will either be sheep or goats. Those are the only two options. There is no middle ground.

Brittany Johnson speaks at a news conference in downtown St. Louis on Dec. 10, 2019, urging the release of her father, Lamar Johnson, from prison. Advocates for Johnson delivered 25,000 petition signatures in support of him to the St. Louis office of Missouri Attorney General Eric Schmitt. (Jim Salter/Associated Press)

When asked what he needed from fellow Christians in this moment of trial, Lamar Johnson humbly said, “I would thank your readers for their prayers and ask that they lift up to God that the truth and our continued faith and trust in him frees us all.”

But on his behalf we’ll urge you to do more than just pray. Praying for Johnson is a necessary and important place to begin. However, we cannot stop until he is released from prison. Until then, we must also speak out against this wrong, raise awareness about his ordeal, and advocate to our leaders that we demand (and he deserves) his freedom.

You can learn more from the Midwest Innocence Project about their efforts to free Johnson, and how you can support their work. If you are a resident of Missouri, you can also contact Gov. Mike Parson and Attorney General Eric Schmitt to urge them to ensure Johnson’s release.

As the author of Hebrews admonished in chapter 13 of that book, “Continue to remember those in prison as if you were together with them in prison, and those who are mistreated as if you yourselves were suffering.”

As a public witness,

Brian Kaylor & Beau Underwood

P.S. Want to support Christian journalism like what you just read? Subscribe to A Public Witness today. Thank you to our subscribers as you help sustain this ministry and help tell important stories like this one! You can also support us by sending this issue to friends you think should subscribe.